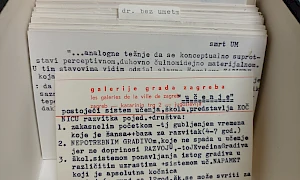

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

In his dispatch from the summer school 'Landscape (post) Conflict' Giulio Gonella revisits the pages of his notebook, prompting a reflection on the questions and impulses that run throughout the week, as well as the act of archiving itself.

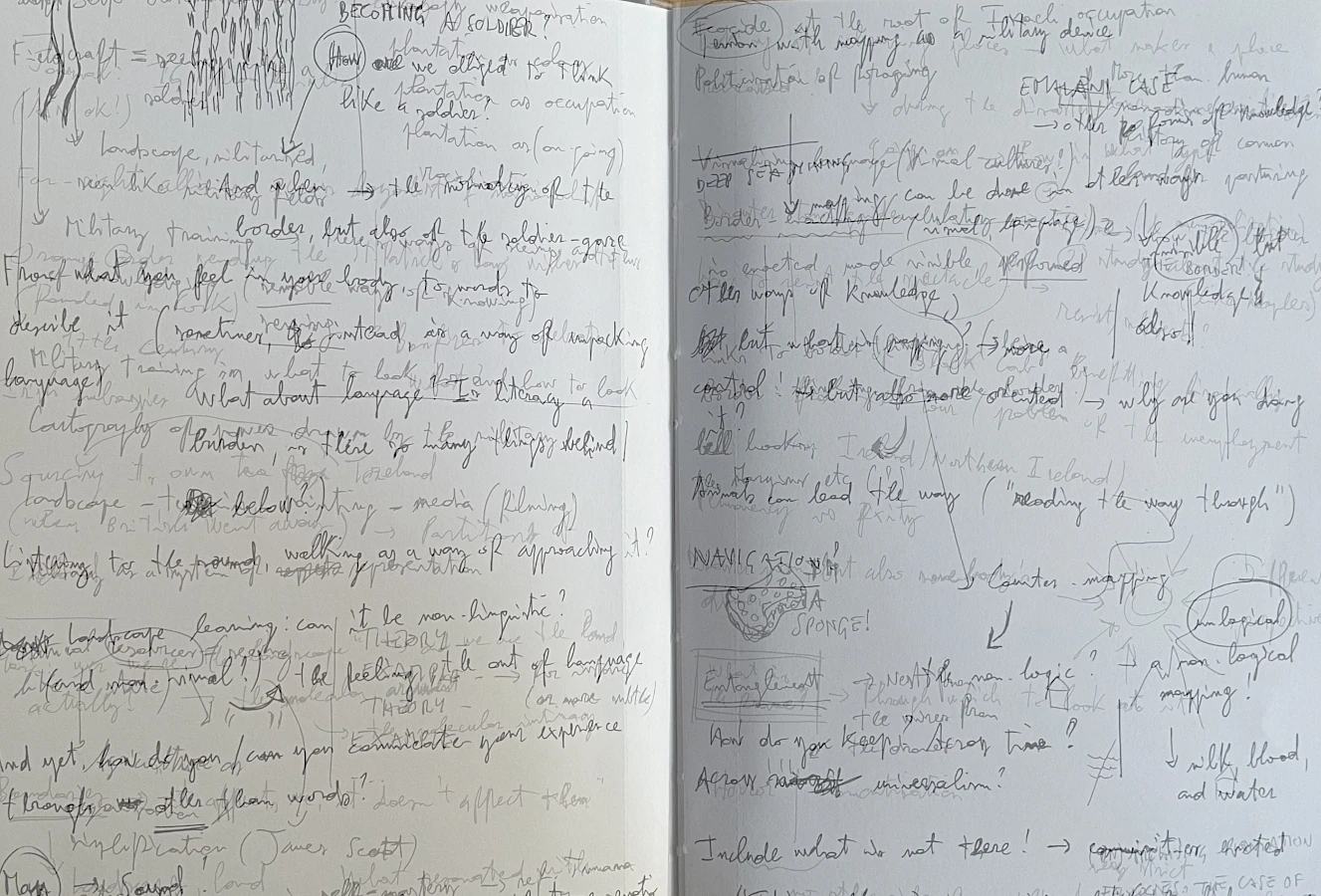

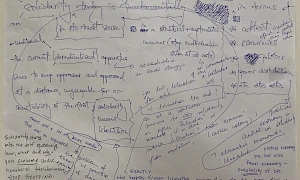

I am listening to Kneecap on a Dublin to Paris flight that will bring me back home. Sun illuminates the aisle of the plane as French kids around me exchange thoughts and words, correcting each other’s language after the English-learning holiday they probably undertook in the country. I had to check in my bag – something that I am not used to do for such short flights and, the object I was most scared to leave behind, apart from my laptop, was the summer school notebook. It was given to us the first day at IMMA, the Irish Museum of Modern Art that would host us these days. The suggestion was to use it to track anything that might ‘speak to us’ in the days ahead. It soon came to contain all the stimuli, words, ideas, and suggestions of a week: thousands of questions, openings, and question marks populate its pages. Its thick, detachable A5 white sheets arguably came to be carved with the marks of (shared) time; reading it again, means to leap back into the memories of an intense week. It’s a deep-dive in intensity.

1. To a certain extent, the notebook reproduces on a micropolitical scale our personal, private attempt to materially archive the (impossible) plural narratives around a (post) conflict land. Brackets are essential here: ‘so far for the post-conflict’ was arguably every participant’s recurring thought these days, as we experienced the withstanding presence of the Troubles across the landscape of the North of Ireland. We could feel such a presence in the streets; more so, we could touch and see its materialities. The murals of Belfast were its most poignant, visible traces. Two raised fists showed the solidarity between the Irish cause for independence and the liberation of Palestine. On the same street, stood memorial sites to those killed. But others, less explicit memorials emerged: buildings carried the holes of past gunshots. Peace line walls still stand; in some areas, metallic gates are opened by the day, but closed at night. Every place we visited in Belfast spoke more of an ever-going conflict than of its wished post-phase.

West Belfast, July 2025. Photo: Giulio Gonella

Through the pages of my notebook, I could turn these events into a language of memory – one that tentatively archives, registers, and translates facts on paper. As such, language also actively participated in shaping those events, by projecting meanings into them, as well as partially transposing some (always incomplete) bits of information. I translated the walls. I made them present in yet another place. To my ear, things ever only reverberate in English; they echo. (I came to understand that the ‘e’ in ‘echo’ is /e/, while the e in ‘ego’ is /iː/. I felt relieved and yet troubled by this difference). On my notebook, instead, things stood precariously. They fixate(d).

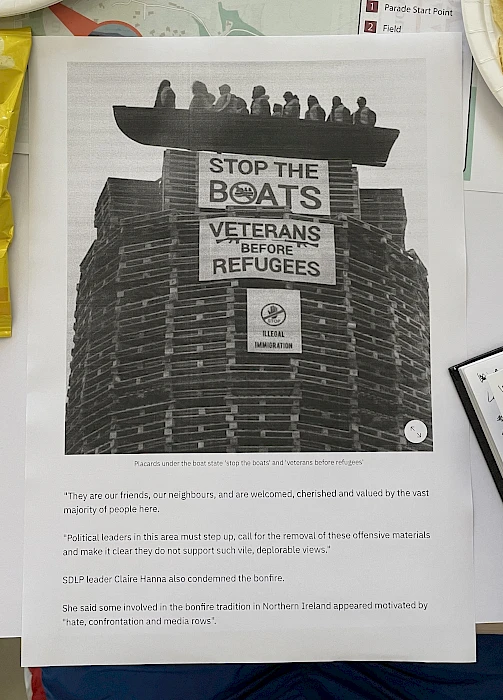

2. On the way to Belfast, we noticed huge stacks of pallets towering over the suburban landscape. Bonfires, Nikita told me some days later, are symbols of the unionist/loyalist cause, as they were arguably lit up to show the King its way to Ireland at some moment in history. Today, they stand as memorial architectures to the protestant support of the unionist cause, yet only for a few days: every 12th of July, they are set on fire, disappearing into toxic ash. Recently, controversies ignited over some of them, as they were spotted carrying signboards against migrants. Signs would read: Migrants go home, or Stop the boats (the slogan against immigration used by former British PM Rishi Sunak in 2023). On one bonfire, a sign read Veterans before refugees; under the first word, stood the symbol of two rifles. On the top of the piled pallets, a kayak-like boat with some fake black busts was ready to be set on fire.

Bonfire in suburban Belfast. Photo: Garry Loughlin

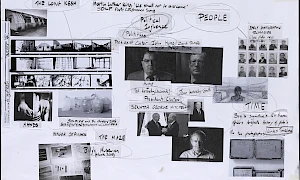

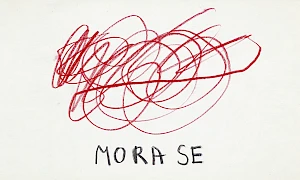

Collage materials. Photo: Giulio Gonella

Bonfires are ephemeral architectures, rebuilt and destroyed every year. They stand for a few days as unequivocal monuments of colonial violence and yet, they perform such violence through absence – by literally fading into air. I am reminded of Christina Sharpe: ‘antiblackness is as pervasive as climate’.1 Fake black bodies were placed on top of the stacks to be burned. Bonfires are a controversial practice, I acknowledge, also for the environmental threat they pose.

3. The story goes that everyone remembers the name of Herostratus, the individual who set fire to the Temple of Artemis, but not the name of the architect who built it.2 Destroying is often a more spectacular, remembered gesture, than patiently designing, building, and preserving. As much as archiving might entail the keeping of objects and artefacts, we often acknowledge their importance once they are gone — blasted away, or destroyed. What happens then, when objects stop to resonate their stories? The last day of the summer school, we discussed collectively on the entanglement between the body and the landscape. Maria, a Ukrainian artist, said: “we are the landscape”. I read a cry of ephemerality in her words: just as the body decays, so do we, and the grounds around us. Tae, artist and educator, added: “stuff that never dies is not magical”. She told us the story of a book written by a Palestinian artist. As s/he attempted to bring their memories somewhere, in a place where they could be shared, s/he got fatally shot and killed. Memories faded along. Who gets to write histories of the (memorial) landscape, and who erases them? How can we abandon the material resonance of a practice of archiving, towards less dissolutive modalities of memorialising, keeping, and caring? And who gets to speak of such memories? In short: what should I do with my notebook?

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Team of Teams

This project researches citizen participation as a fundamental pillar in the creation of community.

-

–tranzit.ro

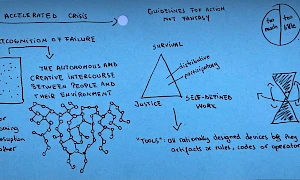

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–MSU ZagrebVan AbbemuseumModerna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – School of Common Knowledge 2024

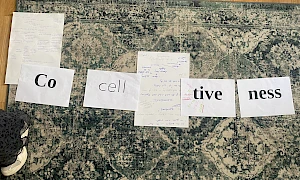

MSU (Zagreb), Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven), MG+MSUM (Ljubljana), ZRC SAZU (Ljubljana) and L'Internationale invite applications for the new School of Common Knowledge (SCK) to be held in Zagreb and Ljubljana 24–29 May 2024. The School of Common Knowledge draws on the network, knowledge and experience of the L’Internationale museum confederation. Its ambition is to be both nomadic and situated, looking at specific cultural and geopolitical situations while exploring their relations and interdependencies with the rest of the world. The SCK is built on the basis laid by the Glossary of Common Knowledge project initiated by Zdenka Badovinac and Moderna galerija (Ljubljana) and continues its co-learning methodology.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–MSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU

School of Common Knowledge 2024

School of Common Knowledge draws on the network, knowledge and experience of the L’Internationale museum confederation. Built on the basis laid by the Glossary of Common Knowledge, a project initiated by Zdenka Badovinac and Moderna Galerija in Ljubljana, it continues its co-learning methodology. Its ambition is to be both nomadic and situated, looking at specific cultural and geopolitical situations while exploring their relations and interdependencies with the rest of the world.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

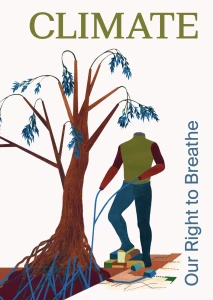

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–Museo Reina SofiaMACBA

Open Call – School of Common Knowledge 2025

Museo Reina Sofía and MACBA Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) invite applications for the 2025 iteration of the School of Common Knowledge, which will take place in Madrid and Barcelona 11-16 November 2025. The School of Common Knowledge (SCK) draws on the network, knowledge and experience of L’Internationale. Its ambition is to be both nomadic and situated, looking at specific cultural and geopolitical situations while exploring their relations and interdependencies with the rest of the world. This year, the SCK program focuses on the contested and dynamic notions of rooting and uprooting in the framework of present – colonial, migrant, situated, and ecological – complexities. Building on the legacy of the Glossary of Common Knowledge and the current European program Museum of the Commons, the SCK invites participants to reflect on the power of language to shape our understanding of art and society through a co-learning methodology.

-

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

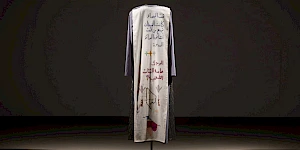

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Cathryn Klasto

In this MA Forum we welcome artist and researcher Cathryn Klasto. This talk will share some working insight into Klasto’s ongoing book project ‘Space Trekking’. The book is a collection of visual essays which tries to reveal the relationship between artistic research, ethics and interstellar spatial phenomena storied within the Star Trek universe.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

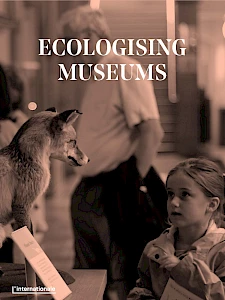

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Glossary of Common Knowledge, Vol. 2

Schools -

Glossary of Common Knowledge

Schools -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

Towards Collective Learning, or, Decompartmentalizing Education

María Berríos, Fran MM Cabeza de Vaca, Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide, Nick AikensSchoolsSituated Organizations -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Reading list: School of Common Knowledge 2024

School of Common KnowledgeSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: In between the lessons. Staying together in uncertain times, laughing in the face of trouble, and disobeying; the future belongs to us

Antonela SoleničkiSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: The Commonsverse and Situated Organisations – or why the era of big institutions will come to an end

Denise PolliniSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: A Buriti Tree

Lucas PrettiSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Poner el nombre a una causa en tierra extraña

Dagmary Olívar Graterol, Paola de la Vega VelasteguiEN esSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMuseo Reina Sofia -

Dispatch: To whom it may concern – the voice of the censor and re-calibrating words as an act of survival

AnonymousSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: A Silent Conversation

Anela DumonjićSchoolsModerna galerija -

Taking Part. A Guide to Participatory Tools and Techniques

EN esSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMuseo Reina Sofia -

Atención: participar en el Museo de los Comunes

Fran MM Cabeza de VacaEN esSchoolsSituated Organizations -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Schools: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardSchools -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

Reading list: October School. Reimagining Institutions

October SchoolSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimateMSU Zagreb -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

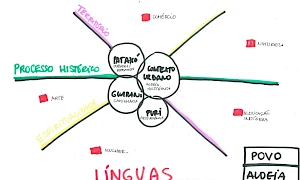

Algumas coisas que aprendemos: trabalhando com cultura indígena em instituições culturais

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteEN ptLand Relations -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Dispatch: Notes On Generosity

Amanda Macedo MacedoSchoolsMuseo Reina SofiaMACBA -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations -

Dispatch: The first and obvious separation is between

KroplyaSchoolsMuseo Reina SofiaMACBA -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations