Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

In her dispatch from the summer school 'Landscape (post) Conflict' researcher Amanda Carneiro reflects on escape and fugitivity across contexts, landscapes and languages.

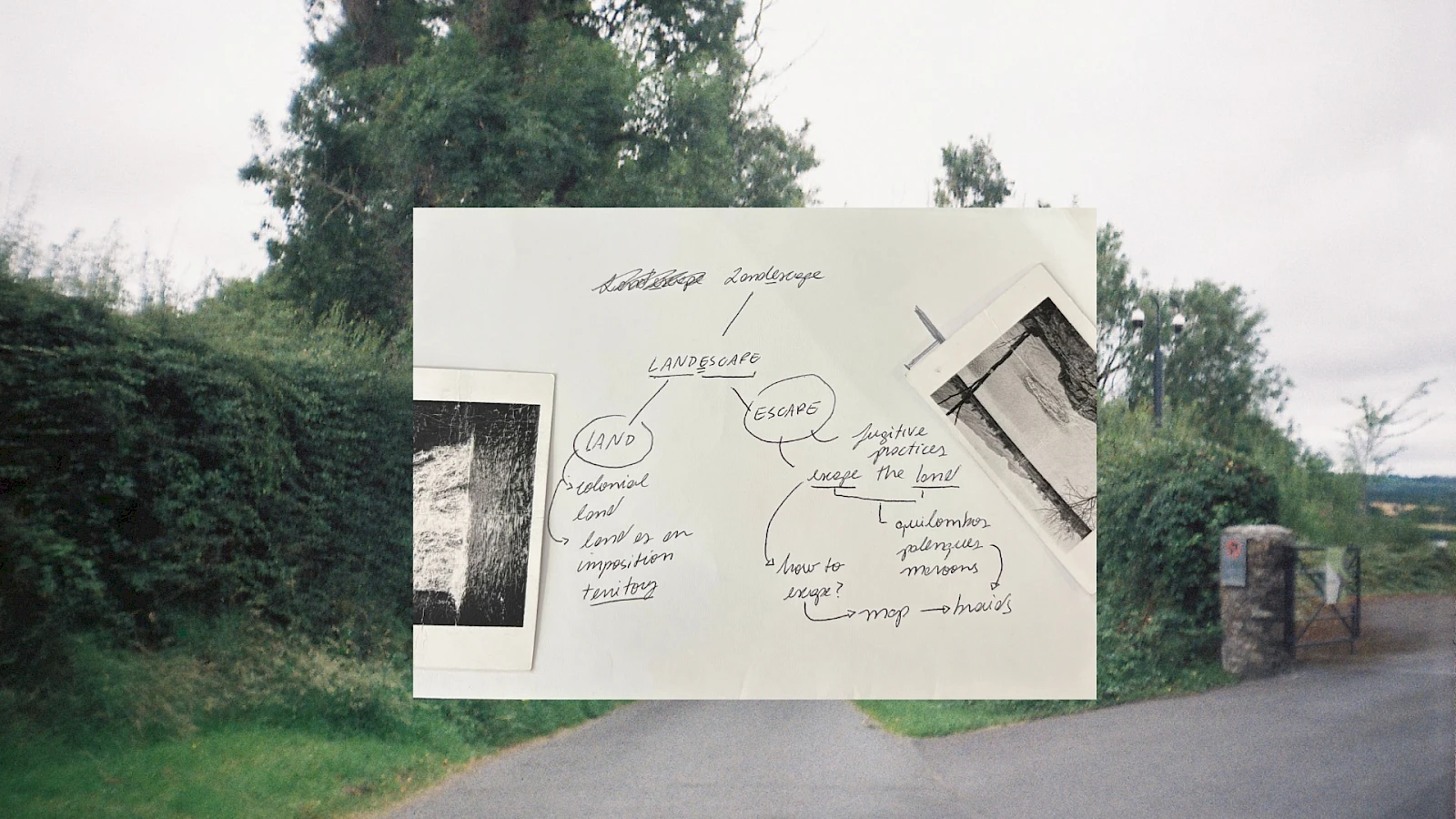

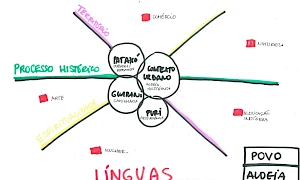

Amanda Carneiro, Collage I, L’Internationale Museum of the Commons Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict, 2025

Five of us gathered in the studios on the left side of IMMA, the Ireland Museum of Modern Art. Each one from a different place: Ukraine, Brazil, Canada, USA, Ireland. Different places, different conflicts. A lot of similarities emerged as we shared our understandings and our suggestions of a lexicon that could compose shared understandings of: self-determination, fieldcraft, natural resources, visualising language, border-enacting, border-thinking and entanglements.

A particular word stood out: landscape, without an e. For Latin language-speakers, it is a common mistake to add vowels in words started by ‘s’, as the mute s sound is rarely used. As I started erasing the word and trying to rewrite it, I found myself writing it, once again, ‘landescape’, with an e. Sabine’s words, my colleague from the summer school, came to my mind: ‘no one owns the language, there is no right or wrong.’

Can there be anything as ‘right or wrong’ in languages as violent as the languages of empires? What is an ‘English mistake’? An e in a word? In the face of more problematic and violent actions attached to the possible correspondents of an ‘English mistake’, I stayed with landescape and faced what it was telling me. What does it mean to escape the land?

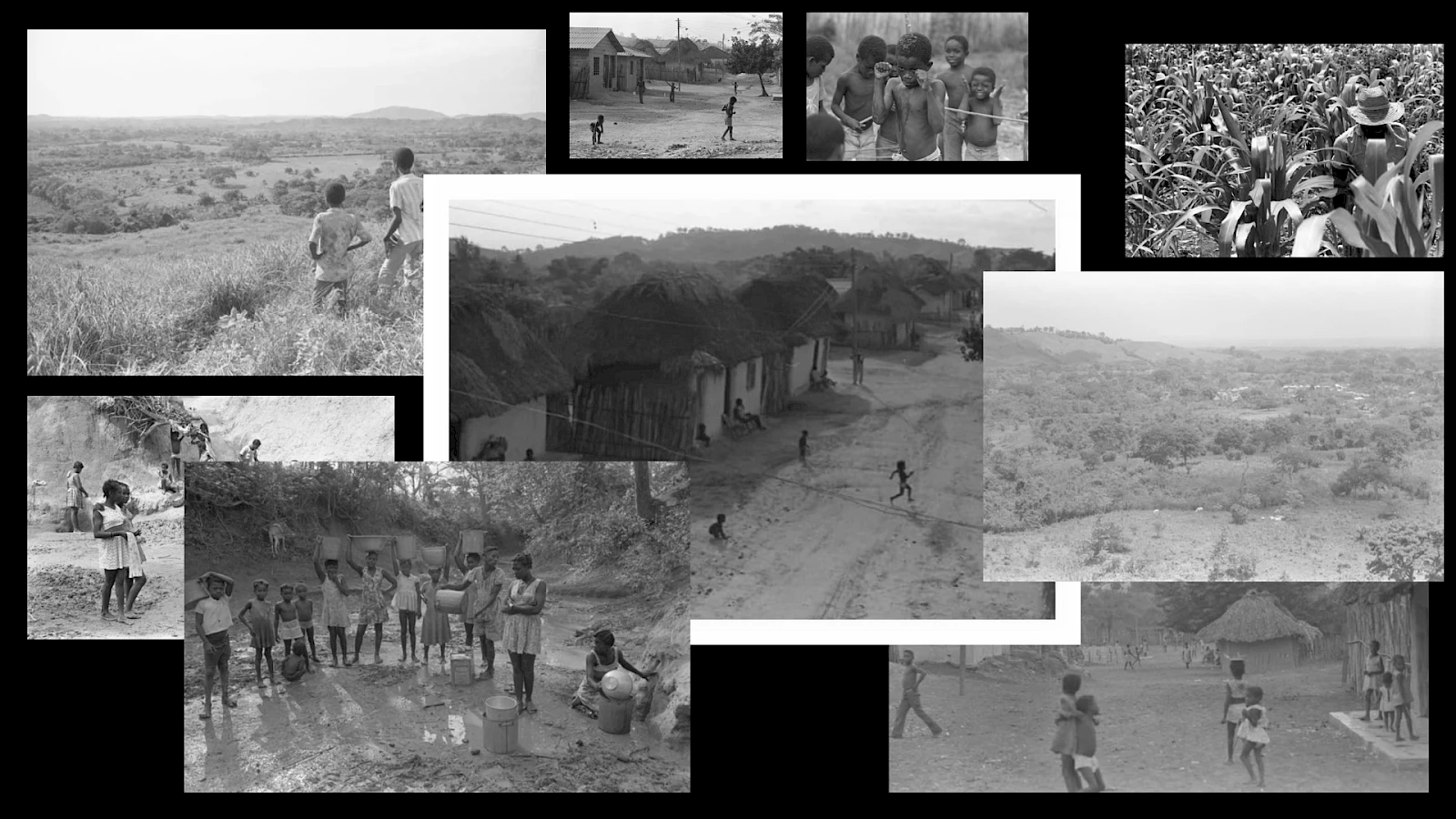

Amanda Carneiro, Collage II, L’Internationale Museum of the Commons Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict, 2025

Escaping here aligned closely with notions of fugitive planning, or the necessity of making maps, a fugitive cartography that led the way out of the dominant and colonial notions of a ‘land’. The land itself is an idea. The soil, a piece of ‘land’, does not know it is a land. It is a bigger set of laws, of people, articulations and mostly, of words, which confine the soil under the violent grammar of territoriality and state logic. If we were to escape the idea of a land, what would a cartography of the act of escaping look like? A possible answer lies close to the history of cornrows, braids made by women in Colombia, when they were confined inside senzalas.

Amanda Carneiro, Collage III, L’Internationale Museum of the Commons Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict, 2025

Cornrows is a traditional hair braiding technique of closely braided styles, in which the hair is braided closely to the scalp in straight rows or more intricate patterns. Senzalas were the enslaved quarters. The word comes from the Bantu language Quimbundo, meaning ‘dwelling’. In colonial South America, it became a living quarter for enslaved individuals. Those precarious accommodations, lacking any privacy or luxury of any kind, were described as overcrowded and unsanitary. 50km away from the Caribbean Sea, women mapped survival through an ancestral braiding technique. When people were trafficked all over Africa and brought to the other side of the Atlantic, a painful subtraction operation was articulated. It meant not only losing one’s language and family but also losing geographical reference. Life played by the rules of a foreign land, a foreign language and mostly, a foreign landscape.

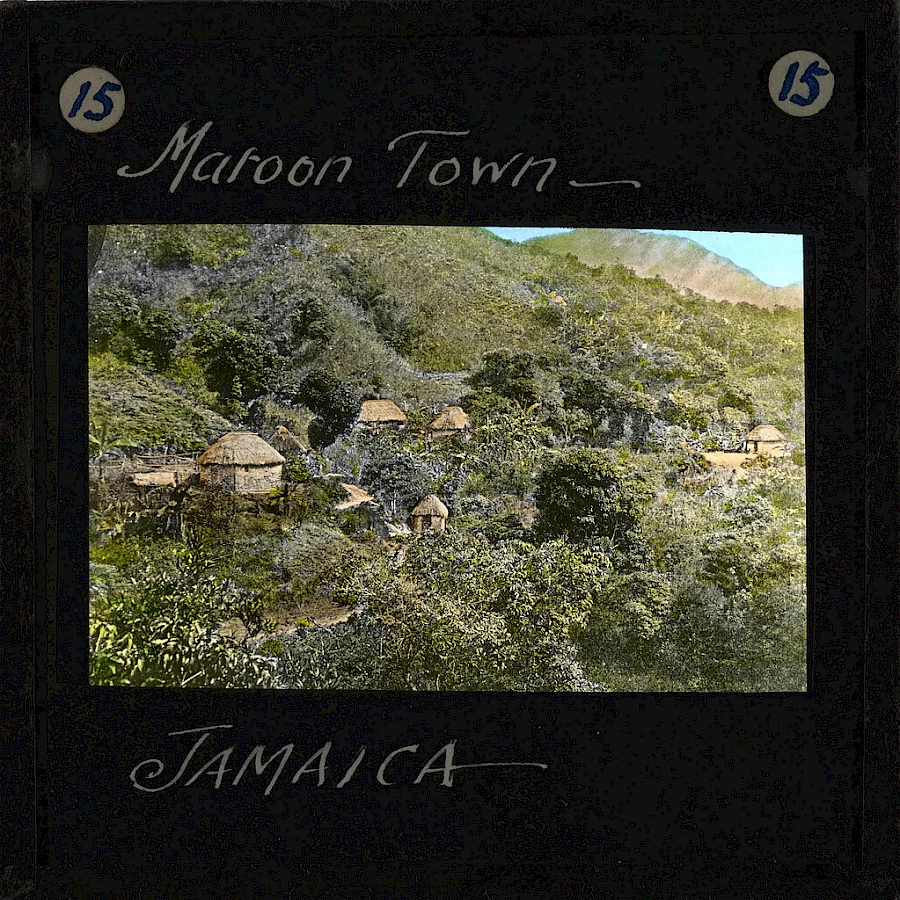

Accompong, Jamaica, early 20th century, Fæ is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

However, whenever forced to go from farm to farm, they paid attention to the roads, becoming familiar with specific landmarks. By visualising the roads and the forests, they translated escape routes into maps. Braids have always carried deep cultural significance, indicating tribe, age, marital status and social rank. After the forced crossing of the Atlantic, they carried the possibility of freedom. The braids were used as a secret code, indicating the way through which they could escape. In an activity of cartography, the scalps became maps to freedom.

But the map to freedom would not mean just an escape route, it meant to arrive in the palenques, quilombos or maroons. These three words represent very similar spaces in the colonial American continent, referring to communities formed by cimarrons, the people who escaped the plantation regime and established independent settlements. Quilombo is more commonly used in Brazil, palenque in Colombia and maroon in the Caribbean.

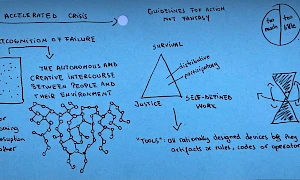

In the hairstyles, women also kept objects that would be useful when they arrived at the palenques, like matches, gold nuggets or seeds. To plan escapes, they gathered and drew maps on the scalps of younger women. The different patterns of braids would mean different things. For example, a twisted braid would indicate a mountain; those that were sinuous, like snakes, indicated rivers or water sources, and a thick braid indicated that in that section, there were soldiers. The hair also represented meeting points, marked by various lines of braids, that converged in the same place, each representing a possible path. If they would meet under a tree, they would finish the braid vertically and upwards, so that it would stand up. If it was by the riverbank, they flattened it in the direction of the ears. Additionally, the braids were sometimes of different lengths along the same paths, indicating to different groups how far they should go.

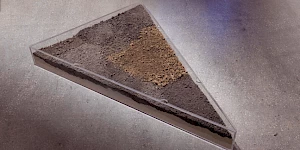

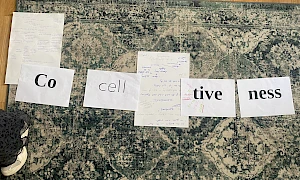

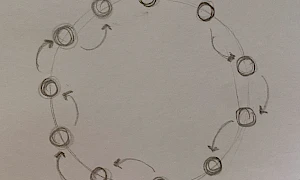

Amanda Carneiro, Collage IV, L’Internationale Museum of the Commons Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict, 2025

The maps were not solely representing geographic characteristics, they would communicate what the escape strategy would be. As I return to the initial task of proposing a new lexicon for landscape, I realize that it is through our collective voices and words that a lexicon of escape can begin to take shape:

Amanda Carneiro, Collage V, L’Internationale Museum of the Commons Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict, 2025

To escape can mean to think of a land that is not fixed, but imagined, shifting, unfinished, always becoming. What does it take for knowledge to be called ancestral? Does it need to be stable, or only carried, remembered, felt? Stones, bonfires, monuments and archaeological sites are structures that hold memory, but they also confine it. We inherit their weight and must ask: in what ways are they still pushed upon us and how might we loosen their hold? Liberation may not lie in rejecting these forms outright, but in learning to walk alongside them differently, seeing them not as final truths, but as starting points, porous and alive, where other stories might also take root.

Amanda Carneiro, Collage VI, L’Internationale Museum of the Commons Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict, 2025

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Team of Teams

This project researches citizen participation as a fundamental pillar in the creation of community.

-

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–MSU ZagrebVan AbbemuseumModerna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – School of Common Knowledge 2024

MSU (Zagreb), Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven), MG+MSUM (Ljubljana), ZRC SAZU (Ljubljana) and L'Internationale invite applications for the new School of Common Knowledge (SCK) to be held in Zagreb and Ljubljana 24–29 May 2024. The School of Common Knowledge draws on the network, knowledge and experience of the L’Internationale museum confederation. Its ambition is to be both nomadic and situated, looking at specific cultural and geopolitical situations while exploring their relations and interdependencies with the rest of the world. The SCK is built on the basis laid by the Glossary of Common Knowledge project initiated by Zdenka Badovinac and Moderna galerija (Ljubljana) and continues its co-learning methodology.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–MSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU

School of Common Knowledge 2024

School of Common Knowledge draws on the network, knowledge and experience of the L’Internationale museum confederation. Built on the basis laid by the Glossary of Common Knowledge, a project initiated by Zdenka Badovinac and Moderna Galerija in Ljubljana, it continues its co-learning methodology. Its ambition is to be both nomadic and situated, looking at specific cultural and geopolitical situations while exploring their relations and interdependencies with the rest of the world.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–Museo Reina SofiaMACBA

Open Call – School of Common Knowledge 2025

Museo Reina Sofía and MACBA Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) invite applications for the 2025 iteration of the School of Common Knowledge, which will take place in Madrid and Barcelona 11-16 November 2025. The School of Common Knowledge (SCK) draws on the network, knowledge and experience of L’Internationale. Its ambition is to be both nomadic and situated, looking at specific cultural and geopolitical situations while exploring their relations and interdependencies with the rest of the world. This year, the SCK program focuses on the contested and dynamic notions of rooting and uprooting in the framework of present – colonial, migrant, situated, and ecological – complexities. Building on the legacy of the Glossary of Common Knowledge and the current European program Museum of the Commons, the SCK invites participants to reflect on the power of language to shape our understanding of art and society through a co-learning methodology.

-

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Cathryn Klasto

In this MA Forum we welcome artist and researcher Cathryn Klasto. This talk will share some working insight into Klasto’s ongoing book project ‘Space Trekking’. The book is a collection of visual essays which tries to reveal the relationship between artistic research, ethics and interstellar spatial phenomena storied within the Star Trek universe.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Glossary of Common Knowledge, Vol. 2

Schools -

Glossary of Common Knowledge

Schools -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

Towards Collective Learning, or, Decompartmentalizing Education

María Berríos, Fran MM Cabeza de Vaca, Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide, Nick AikensSchoolsSituated Organizations -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Reading list: School of Common Knowledge 2024

School of Common KnowledgeSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: In between the lessons. Staying together in uncertain times, laughing in the face of trouble, and disobeying; the future belongs to us

Antonela SoleničkiSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: The Commonsverse and Situated Organisations – or why the era of big institutions will come to an end

Denise PolliniSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: A Buriti Tree

Lucas PrettiSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Poner el nombre a una causa en tierra extraña

Dagmary Olívar Graterol, Paola de la Vega VelasteguiEN esSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMuseo Reina Sofia -

Dispatch: To whom it may concern – the voice of the censor and re-calibrating words as an act of survival

AnonymousSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: A Silent Conversation

Anela DumonjićSchoolsModerna galerija -

Taking Part. A Guide to Participatory Tools and Techniques

EN esSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMuseo Reina Sofia -

Atención: participar en el Museo de los Comunes

Fran MM Cabeza de VacaEN esSchoolsSituated Organizations -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Schools: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardSchools -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

Reading list: October School. Reimagining Institutions

October SchoolSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimateMSU Zagreb -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Algumas coisas que aprendemos: trabalhando com cultura indígena em instituições culturais

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteEN ptLand Relations -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Dispatch: Notes On Generosity

Amanda Macedo MacedoSchoolsMuseo Reina SofiaMACBA -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations -

Dispatch: The first and obvious separation is between

KroplyaSchoolsMuseo Reina SofiaMACBA -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations