Making Ground

The following short-form interview builds on Kasangati Godelive Kabena’s contribution to Climate Forum I – a screening of Made 10 (2023), as part of the afternoon session titled ‘Plant Bodies as Archive’. Touching on the conceptual and thematic dimensions of this work in relation to ecology, climate and worldmaking, Kabena situates her practice within the architectural and agricultural history of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), the construction of which disrupted pre-existing farming communities. In her Made series, Kabena employs collaboration as both a performative act and as a speculative and critical tool to question the status, agency and emancipation of bodies – whether human, vegetal or spatial. In Made 10, through the recurrent motif of lettuce, she stages acts of planting, uprooting and chopping as choreographic gestures that symbolize transformation, displacement and the hidden histories embedded in land and materiality.

Nkule Mabaso: At the time of Climate Forum I, due to technical challenges, you could not give us insight into the work you had produced. Please now describe the work, and shed light on the insight you wanted to share through it.

Kasangati Godelive Kabena: The Made series of performances (2021–23) focuses on the potential of performance as a tool and historical referent. They explore the political status of bodies and their emancipation – beyond just those of human entities. My interest in the corporeal was fuelled by my constant presence in front of a camera (Canon 1300D) between 2018 and 2021, during which I made a series of self-portraits that led to several performance works. The Made performances use a specific discursive framework and production method to negotiate questions of egalitarianism, collaboration, and more. By exploring ideas of democracy and the distribution of power through the performance itself, a self-referential zone of dissensus emerges. Proposing a speculative analysis, the research investigates the political status of bodies and their potential emancipation beyond the corporeal.

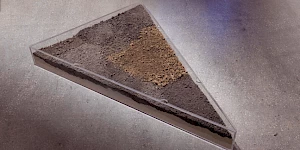

We could say that the lettuces that appear in the work I showed in the Climate Forum open a reflection on bodies and how they can be seen. The state of these lettuces – planted, uprooted and chopped – become evidence of hidden events, connecting the lettuce field and the architectural history of KNUST (Kwame Nkrumah University of Technology).

I read ‘Land Imaginaries: The Gift’ (2024) by Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh and Łukasz Stanek just after collaborating with farmers for the production of Made 10.1 In the article the authors discuss the architectural paradigm of KNUST and how its formation dislocated an older ecology of agricultural practices. There were many land and farming communities that existed on the site of KNUST’s campus before its construction, for many of whom its building was hugely disruptive. The few remaining farms visible on campus now, fragments of cultivated land, have come to constitute a self-referential proposal of how the land might be, as it was once, used or as Ohene-Ayeh and Łukasz Stanek say ‘the takeover of the land by the university is not an event of the past but rather an event that continues to take place every day’.2

The question of land here reminds me that bodies in this context do not always reveal meaning, relations and possibilities. In this sense they are in withdrawal. Similarly, the events they form remain volatile. Therefore, any attempt to address, through art practice, what happened to the communities tends to result in a form of performative operation.

NM: In the work you produced, we see farmers picking lettuce that you then chop on a table. I read the work as an ecological movement between 'bodies’ or materials, those being yourself and the lettuce. Can you describe your approach to the site and the process of conceptualising the performance?

KGK: At first, the farms that are present at KNUST were an aesthetic frame. But my working at one was not a question of using the farm as a site but rather of the farm itself becoming the work. It would have been naive to think of the work as just me chopping lettuce – the important thing to remember is that bodies always form discursive sites. I think of the stages in the choreography of uprooting, chopping, etc., as different forms of relation to objects or bodies. Every stage in this choreography changes the approach to the lettuce. From being planted at the farm to being uprooted, chopped then discarded, these various stages offer ways to direct attention towards the relations between the lettuce, me and the performative moment. This is a way to think performativity not as something that takes place over a period of time but as an event in a single moment, always staged by different, human and other-than-human entities, not in order to be acknowledged but as a political stance.

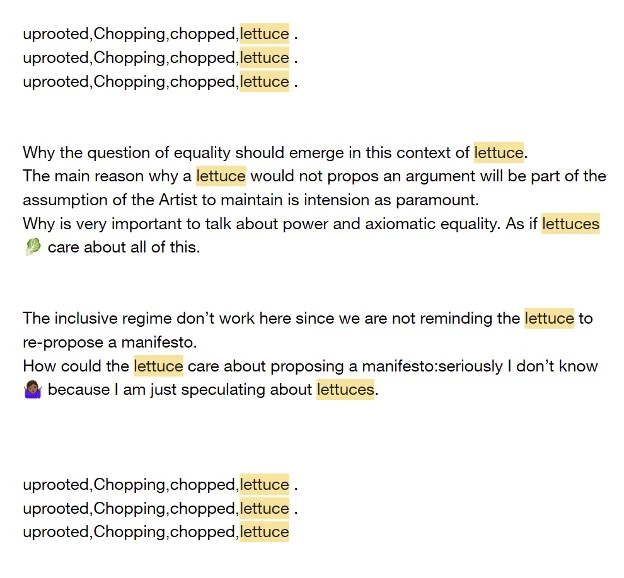

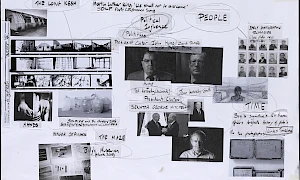

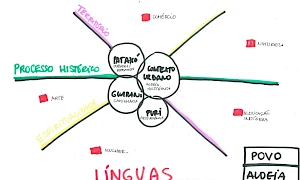

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Made 10 performance score, 2023

NM: What role does collaboration – with other artists, institutions, or even non-human entities – play in your practice?

KGK: A few weeks ago, I was saying that I think working with different institutions, artists, entities and so on is a mess! Everything is so entangled that collaboration does not necessarily mean working together, but also responding to what is denied or not recognised in the working process. The Made series questions collaboration as a possibility or aim, we could say, suggesting that collaboration will fail because the self-referential nature of different entities constantly undermines it. Made 10 creates a space where the positioning of bodies always imposes a certain type of event, which appears not only as a presence, but sometimes as a projected proposition, capable of being staged in a choreographic and rhythmic manner. This stage becomes a reference to this event, and not the event itself.

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Made 10 (film stills), 24 November 2023, duration: 1 hour 30 min. Shot on location at KNUST, Kumasi, Ghana. Contributors Aduku Thimathy, Awintoo Samuel.

NM: Your practice seems to open alternative timelines, moving between what happened, what might have happened, and what could still happen. How do you think about ecological time in relation to this work?

KGK: What is interesting about ecology is that it holds a form of interobjectivity, refusing to acknowledge time.3 Here, the event becomes more relevant than time passing, because situations cannot be relegated to the discursive arena as time-lapses, but rather exist as singular propositions that cannot be grasped and framed. These unseen possibilities that cannot be experienced are what interests me.

NM: What are you currently working on or thinking through?

KGK: I am working on a project that explores reproduction as a process, and how it can be manufactured, through archival images of the Basenji dog from the DRC (Democratic Republic of Congo).

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–tranzit.ro

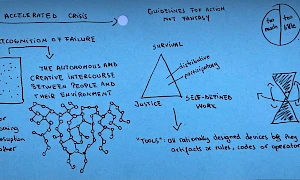

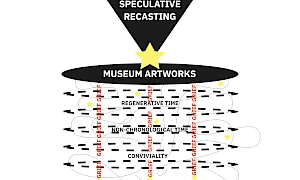

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

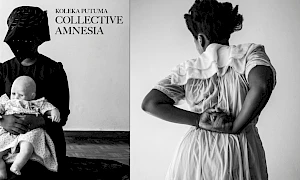

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Algumas coisas que aprendemos: trabalhando com cultura indígena em instituições culturais

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteEN ptLand Relations -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations