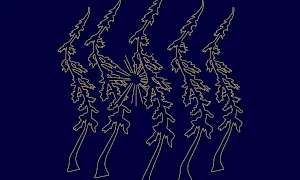

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

The Kulagu is the loudest bird in the Pantaron forest in the Philippines, where the Indigenous peoples have been displaced from their land and subsequently ‘red-tagged’ for speaking out. The Kulagu Tu Buvongan collective borrows its name from the bird and are a collective of majority Pantaron Range Lumad members. Here they introduce their story and their practice. The piece extends their contribution in Climate Forum IV ‘Our world lives when their world ceases to exist’.

Amid the pandemic lockdowns in 2021, Manobo and Tinananun Indigenous elders in the self-organized camps in Davao City recreated forest sounds from memory and explained their meanings and use. The sounds and stories behind these sounds were documented and later taught to children in the camps, many of whom were born in exile and have never experienced forest life in their ancestral domains. The sounds correspond to different birds, animals and insects, some of which haven’t been seen in years. A bird call recording is for children and future generations to remember: the sound of the forest offers a way of hiding from kidnaps and killings, as well as respecting the forest by learning its voice.

Home of endangered flora and fauna, and the source of several rivers, vast areas of the Pantaron Range have been usurped for large-scale monocrop plantations, mining and logging operations, disrupting the most important watershed and biodiversity corridor in Mindanao. Government and corporate interests have been driving out the Indigenous / Lumad stewards of the Pantaron Range, even labelling them as terrorists (Lumad is the Philippine term for Indigenous people).1 Some Indigenous groups, vocally critical of this injustice, have been displaced and are now exiles in their own land, living in self-organised camps and sanctuaries across the Philippine archipelago; some have gone into hiding under threat of death, and several have been martyred.

Land reform in the Philippines has failed. The current oligarchic Philippine elite continue to perpetuate the injustices committed by Spanish and American colonizers. Mining contracts are made at the expense of Lumad lands, endangering watersheds and entire ecosystems for short-term profit. Since 2016, many human rights defenders, activists, and journalists have been killed in ‘unresolved crimes’ after being ‘red-tagged’ by the government, 2 with no-one held to account for their murder. Farmer and peasant landlessness too go hand in hand with the continued exploitation and forced expulsion of the Lumad.

It is in this context that the Pantaron Mountain Range, which is home to many Lumad peoples, has been exploited via gold mining, logging and infrastructure, causing watersheds to be toxified, the rice fields to be bulldozed and Lumad peoples to be displaced. The mountain range is the source of food, medicine, materials and other necessities for Lumad peoples. This is what we (Kulagu tu Buvongan and Lumad peoples) stand up for, what we defend. The headwaters of most of the major rivers of Mindanao island spring from the Pantaron. The wild animals live in Pantaron. The trees live in Pantaron. Pantaron is gold.

When the logging started, we started organizing. Father Paps told us: ‘Individual action is not enough. There must be collective action from the Indigenous (Lumad) peoples.’ This is how we united with the Manobo from the Pantaron Mountain Range. Defending the mountains is not bad. Protecting the mountains of Mindanao is not bad. My actions are not just for my sake. They are also for the sake of others.

It was in late 2021 that Kulagu Tu Buvongan, a collective of majority Pantaron Range Lumad members, held a series of recording sessions and workshops in the camps in Davao City, focused on forest calls and non-lexical vocables, non-words used in daily forest life that mimic forest fauna sounds. Recreated from memory by several Indigenous elders in the camps who explained their meanings and use – some sacred, some for play – these sounds were later taught to Lumad children, many of whom, as before, were born in exile.

A forest of sounds is a manifestation of these recording sessions and workshops: made by displaced human voices documenting a place they cannot yet return to, a landscape in the midst of disappearance. Kulagu Tu Buvongan’s works are performative at home, and have been shared as installations elsewhere.

The mobilization and production of these recordings was initially supported by OCAC Taipei in 2021, with additional donations by Quezon City-based artist Lyra Garcellano and The Observatory (a rock band based in Singapore), along with the personal resources and initiative of the collective members. Meanwhile, Lumad schools continue to be attacked by state military and paramilitary troops.3 Most of the collective members and people involved are kept anonymous. The raw video documentation materials were lost soon after the recording.

Names of animals in Manobo written on the palm of someone’s hand; also feet, recording equipment and the earth below. Kulagu Tu Buvongan forest sound recording session, Davao City, 2021. Photograph: Kulagu Tu Buvongan collective

Elder reflected in recording equipment documenting Kulagu Tu Buvongan forest sound recording session in Davao City, 2021. Photograph: Kulagu Tu Buvongan collective

Simple instruments fashioned from plant materials with which forest sounds were made in addition to human voices. Kulagu Tu Buvongan forest sound recording session, Davao City, 2021. Photograph: Kulagu Tu Buvongan collective

From the initial workshops in 2021, the collective’s projects have since travelled across the world as iterative installations at various venues: the voices of Pantaron Range elders and their children are presented through a multichannel sound set-up, with the addition of visual components specific to the location.

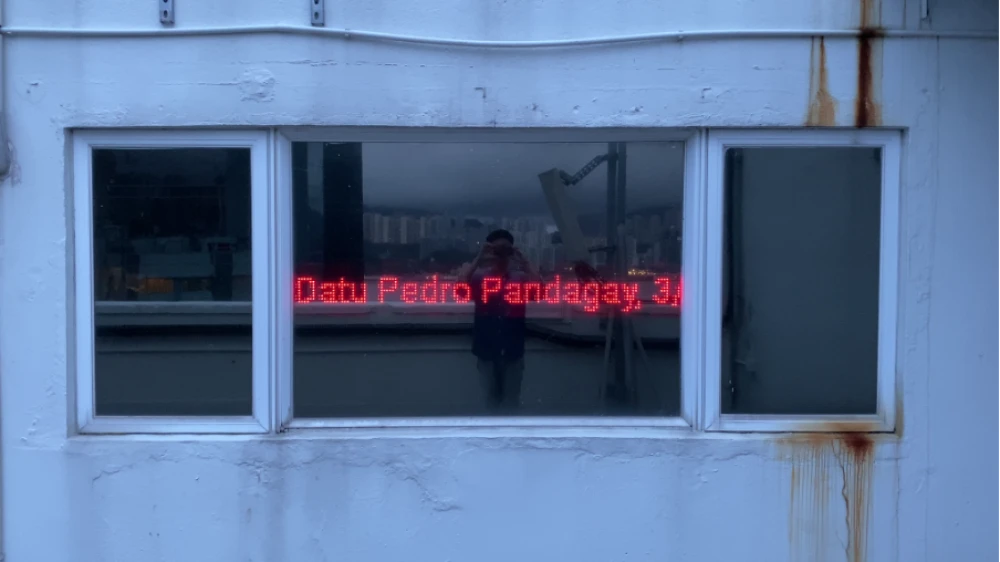

Few people actually realize that Hong Kong’s art space Para Site exists on the top floor of the twenty-two storey building it occupies, which most people know by the more prominent occupant of the first floor, a provider of funeral services. For our 2023 installation there, an LED strip faced out of the windows listing the names of Indigenous activists martyred in the Philippines since the Duterte presidency began in 2016, while the Pantaron Range forest sound recordings wove in and out through the staircase and into the open space. Here, as you looked at the names on the LED, you knew you did so amid Hong Kong and against the backdrop of its development, with its many ties to Philippine migrant labour and to exploitative practices in the Philippines.

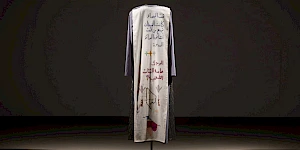

For the 2024 iteration at FONTE in São Paulo, along with the sound component of the work, the names of Brazilian Indigenous activists who were martyred during a similar time period during the Bolsonaro presidency were streamed on another LED alongside the names of those from the Philippines.

Kulagu Tu Buvongan collective, LED strip listing martyred Philippine Indigenous activists, detail of forest sound installation exhibited as part of ‘signals…瞬息: signals… here and there’, Para Site, Hong Kong, 12 August – 29 September 2023. Photograph: Jason Chen

Kulagu Tu Buvongan collective, São Paulo iteration of forest sound installation, exhibited as part of ‘A Fonte Deságua na Floresta’ (A Spring Flows Into the Forest), FONTE, São Paulo, 27 July – August 2024. Photograph: Filipe Berndt

We want our voices to be heard not just in Mindanao or in the Philippines. We want the whole world to hear. We tell them: We do not have any regrets over being red-tagged. Our consciences are clear. There are no intentions behind our activism other than to think and act for the common good. We tell our children that we have no regrets.

Philippine Indigenous activists killed July 2016 to June 20214 :

Joaquin Cadacgan, 9 July 2016

Remar Mayantao, 12 July 2016

Senon Nacaytuna, 12 July 2016

Rogen Suminao, 12 July 2016

Hermi Alegre, 15 July 2016

Makenet Gayoran, 30 July 2016

Jimmy Barosa, 12 August 2016

Jerry ‘Dandan’ Layola, 12 August 2016

Jessebelle Sanchez, 12 August 2016

Jimmy Saypan, 10 October 2016

Venie Diamante, 5January 2017

Veronico Delamente, 20January 2017

Renato Anglao, 3 February 2017

Matanem Pocuan, 4 February 2017

Moryel Latan, 6 February 2017

Emelito Rotimas, 6 February 2017

Jerson Bito, 11 February 2017

Pipito Tiambong, 11 February 2017

Edweno ‘Edwin’ Catog, 16 February 2017

Datu Pedro Pandagay, 23 March 2017

Federico Plaza, 3 May 2017

Mario Versoza, 21 May 2017

Daniol Lasib, 26 May 2017

Ana Marie Aumada, 27 May 2017

Ande Latuan, 6 July 2017

Remond Lino, 12 July 2017

Romy Rompas, 16 August 2017

Roger ‘Titing’ Timboco, 23 August 2017

Obello Bay-ao, 5 September 2017

Erning Aykid, 15 September 2017

Aylan Lantoy, 15 September 2017

Samuel Angkoy, 3 December 2017

Mateng Bantal, 3 December 2017

Pato Celarbo, 3 December 2017

Artemio Danyan, 3 December 2017

Rhudy Danyan, 3 December 2017

Victor Jr Danyan, 3 December 2017

Datu Victor Danyan Sr, 3 December 2017

To Diamante, 3 December 2017

Ricky Olado, 28 January 2018

Ricardo Mayumi, 2 March 2018

Garito Malibato, 22 March 2018

Jhun Mark Acto, 21 April 2018

Dande Lamubkan, 30 April 2018

Carlito Sawad, 23 May 2018

Burad Salping, 25 May 2018

Beverly Geronimo, 26 May 2018

Jose Unahan, 6 June 2018

Nestor Sacote, 10 June 2018

Menyo Yandong, 10 August 2018

Rolly Panebio, 18 August 2018

Jean Labial, 19 August 2018

Rex Hangadon, 15 September 2018

Jimmy Ambat, 7 October 2018

Esteban Empong Sr, 18 November 2018

Rommel Romon, 23 November 2018

Randel Gallego, 24 January 2019

Emel Tejero, 24 January 2019

Randy Malayao, 30 January 2019

Sanito ‘Tating’ Delubio, 1 March 2019

Jerome Pangadas, 15 March 2019

Kaylo Bontolan, 7 April 2019

Datu Mario Agsab, 8 July 2019

Alex Lacay, 9 August 2019

Jeffrey Bayot, 12 August 2019

Bai Leah Tumbalang, 23 August 2019

Sammy Pohayon, 11 September 2019

Romen Milis, 25 April 2020

Roel Baog, 1 May 2020

Reynante Linas, 1 May 2020

Don Don Cenimo, 11 June 2020

Randy Pindig,11 June 2020

Bai Merlinda Ansabu Celis, 23 August 2020

Resky Ma Ellon, 3 November 2020

Deric John A. Datuwata, 5 November 2020

Mario Aguirre, 30 December 2020

Garson Catamin, 30 December 2020

Maurito Diaz Sr, 30 December 2020

Rolando Diaz, 30 December 2020

Eliseo Gayas Jr, 30 December 2020

Roy Giganto, 30 December 2020

Reynaldo Katipunan, 30 December 2020

Artilito Katipunan Sr, 30 December 2020

Jomar Vidal, 30 December 2020

Julie Catamin, 28 February 2021

Randy ‘Pulong’ Dela Cruz, 7 March 2021

Puroy Dela Cruz, 7 March 2021

Abner Esto, 7 March 2021

Edward Esto, 7 March 2021

Angel Rivas, 15 June 2021

Lenie Rivas, 15 June 2021

Willie Rodriguez, 15 June 2021

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–tranzit.ro

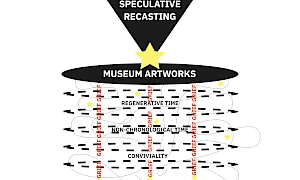

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

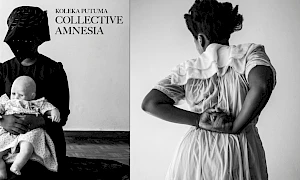

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

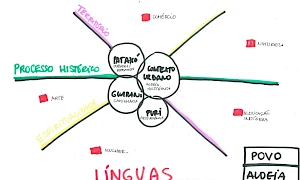

Algumas coisas que aprendemos: trabalhando com cultura indígena em instituições culturais

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteEN ptLand Relations -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations