Black Archives: Episode II. Jazz without a Black body politic

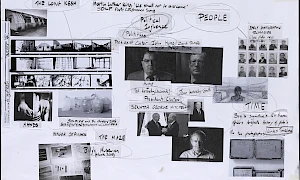

In the second in a three part series researcher Tania Safura Adam continues her excavation of the Black archive in Spain. Here, she draws on extensive archival and literary references to explore the complex, often contradictory role of jazz within the context of Spain since the 1920s and until today: as a form of solidarity and support for Black communities, as part of the avant-garde and as an art form that has been whitewashed and appropriated by the middle classes, overlooking its emancipatory Pan-Africanist drive.

Absence

In torrid August, 1954, I was under the blue skies of the Midi, just a few hours from the Spanish frontier. To my right stretched the flat, green fields of southern France; to my left lay a sweep of sand beyond which the Mediterranean heaved and sparkled. I was alone. I had no commitments. Seated in my car, I held the steering wheel in my hands. I wanted to go to Spain, but something was holding me back. The only thing that stood between me and a Spain that beckoned as much as it repelled was a state of mind. God knows, totalitarian governments and ways of life were no mystery to me. I had been born under an absolutistic racist regime in Mississippi; I had lived and worked for twelve years under the political dictatorship of the Communist party of the United States; and I had spent a year of my life under the police terror Perón in Buenos Aires. So why avoid the reality of life under Franco? What was I scared of?1

This is how ‘Black Archives: Episode I. Radical Internationalism and Pan-Africanism in the context of the Spanish Civil War’ ends.2 It is also how Pagan Spain (1957), the book Richard Wright wrote after his visits to Spain, begins. Throughout the book, Wright observes and depicts a country that is complex in ways both Catholic and pagan, and comes to understand that the fear that ran through him at the border was not unwarranted, particularly in light of the difficulties he had to face because of the colour of his skin. For centuries, Spaniards and Europeans had been exploring, exoticizing, appropriating and interpreting ‘otherness’. Perhaps it was the ostracism and fear of Blackness that had prevailed ever since that made Wright uneasy, as ignorant as he was then of the degree of repulsion that existed under the fascist regime in a country described as ‘primitive, but lovely’ by his friend Gertrude Stein.3 This ignorance could only be addressed by getting right into the belly of the beast.

At this point, Wright was not only confronted with a physical frontier, but with other boundaries as subtle and imperceptible as the ‘colour line’, for his onward journey was as white as the country of Spain itself. He makes no mention of encountering Black people, or ‘morenos’, as they were called at the time, which suggests that this was not a part of his Spanish experience. However, the African American view of Spain was not homogeneous. Langston Hughes, another great figure in Black literature who arrived in Spain some years earlier, chronicles a very different experience:

Negroes were not strange to Spain, nor did they attract an undue amount of attention. In the cities no one turned round to look twice. Most Spaniards had seen colored faces, and many were quite dark themselves. … And in both Valencia and Madrid I saw pure-blooded Negroes from the colonies in Africa, as well as many Cubans who had migrated to Spain. … I found, shortly after my arrival, that one of the most popular variety stars in Madrid was Negro Aquilino, a Cuban, who played both jazz and flamenco on the saxophone.4

Hughes’s relative idealization – and apparent lack of exoticization – of the Black presence he observed in Spain was mediated by his experience as an African American in the United States. This does not mean that forms of oppression did not exist: In his 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. Du Bois introduced the concept of the ‘color line’ to describe the experience of African Americans in a society that excludes them and sees them as ‘other’. This metaphorical line, though invisible, marks a fundamental difference between those who are considered ‘white’ and those who are ‘Black’, and determines the opportunities, rights and social relations of each group.5 Likewise, every Black person travelling through or living in Spain in recent centuries will have experienced a sense of difference and exclusion engendered by racial stereotypes and discrimination, though few have had the chance to tell their stories. Being Black in social spaces where certain deeply rooted imaginaries about Blackness have taken hold inevitably affects any life experience. Juan Latino and Sor Chicaba are among those to have taken the floor to critique and condemn the treatment they received in Spain during the early modern period.6 However, it was not until last century that reflections on racism began to be seen in artistic creations. This was a privilege attained only by those few who raised their voices with no little self-consciousness and trepidation, which could be related to the absence of any form of Black social or political body to represent them. In any case, the bewilderment produced by the Black experience in Spain was felt across the social scale, from everyday people to celebrities. Examples include Kid Tunero, Elsie Bayron, Jack Johnson, La Perla Negra, Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, Dizzy Gillespie, Louis Armstrong, Nicolás Guillén, Antonio Machín, Benny Carter, Harry Fleming, Negro Aquilino and Joséphine Baker, among many others.

Elsie Bayron on her European tour, Budapest Royal Hotel, 1936/37. Image courtesy blackjazzartists.blogspot.com

Negro Aquilino in 1935. Image courtesy palabrasdelaceiba.wordpress.com

From the fifteenth to the seventeenth century there were Black communities in Spain, in places such as Andalusia, the Canary Islands, Madrid, Valencia and Barcelona.7 These were formed by enslaved people, mostly Africans, who were not considered – not legally recognized as – people, but their presence did leave an indelible mark on the cultural landscape, nonetheless.

It was in this period of early modernity that the foundations of Spain’s relationship with Blackness were laid, anchored in racist and denigrating stereotypes. Certain external biological characteristics came to be symbols of a social condition, and the word esclavo/esclava (slave) began to be replaced with negro/negra (black). From then on, any individual with a dark complexion was likely to be regarded as an enslaved person: that is, as an impoverished, infantilized person unable to cope with the world and with a corresponding need for permanent tutelage.8

This imaginary of Blackness was portrayed and reinforced through music, theatre and literature.9 As Francisco Zamora Loboch states in Cómo ser negro y no morir en Aravaca. Manual de recetas contra el racismo (How to be Black and not die in Aravaca: Recipes against Racism, 1994):

From a racist point of view, the Spanish Golden Age was a harsh, intolerant era, rough as the kiss of the ring to the windpipe. Some writers are virulently racist, others the opposite. Cervantes and Quevedo captained both extremes.10

The Black population was drastically reduced by various causes from the seventeenth century until the 1970s, when a period of Black immigration, mainly from Africa, began in Spain. There was a small exception to this in the interwar period in Barcelona’s Barrio Chino, then known as Little Harlem because of the concentration of Black musicians and boxers.11 The newspapers of the time went so far as to describe a ‘Black invasion’ coinciding with the jazz phenomenon, even saying Blackness was in fashion.12 The exceptional nature of this claim is reflected in Kid Tunero, el caballero del ring (2016), in which, because he ‘felt he owed it to him’, journalist and researcher Xavier Montanyà delves into history to investigate and describe the life of this Cuban boxer in Barcelona:

In Carrer Nou de la Rambla, Barcelona’s Harlem, Cubans were king. It could be said that they had spontaneously formed a tumultuous community that brought together Blacks of various origins: Puerto Rico, Martinique, Senegal, Alabama, Georgia and, the poorest of all, the natives of Equatorial Guinea, the Spanish colony in Black Africa. The natives of Fernando Poo and Rio Muni were the most destitute of the community. They could be seen in Chinatown picking up cigarette butts and other rubbish from the ground, or acting as street announcers for African safari films.13

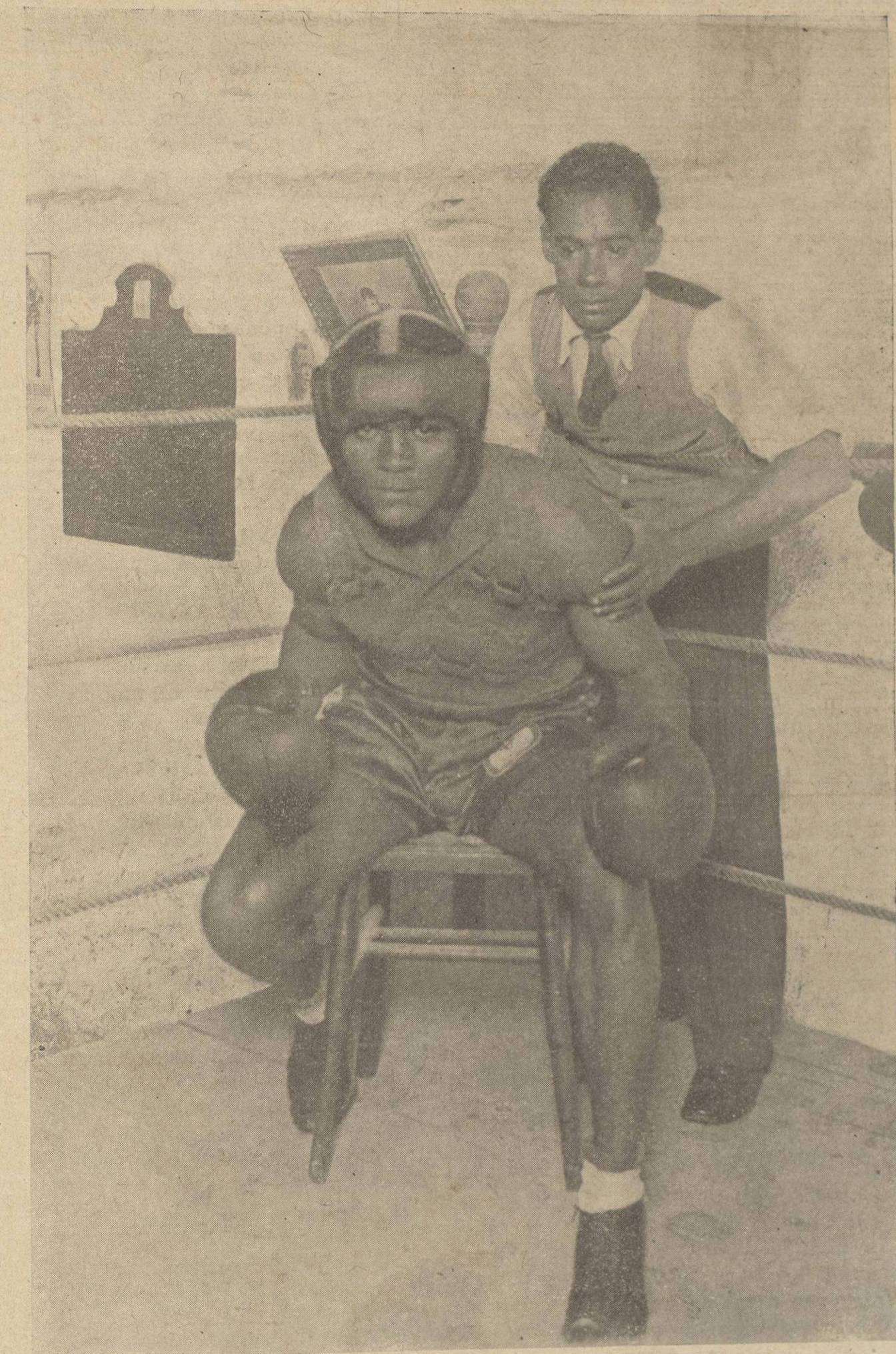

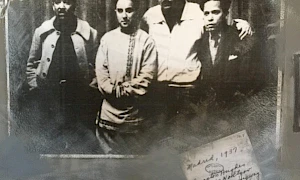

Photograph of Kid Tunero included in Xavier Montanyà’s book Kid Tunero, el caballero del ring, La Rioja: Pepitas de Calabaza, 2016

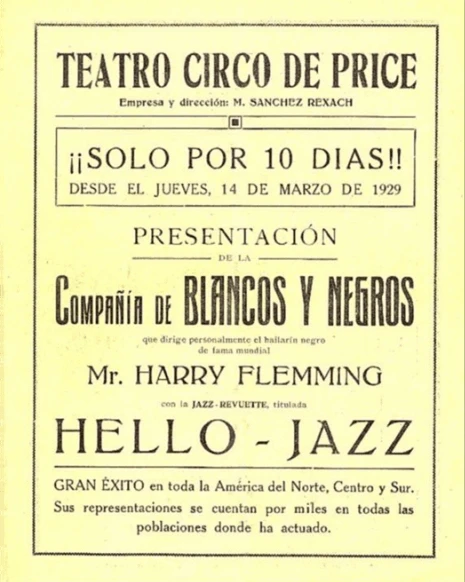

Poster for performance by Mr. Harry Flemming (sic.) at Teatro Circo Price, Madrid, 1929

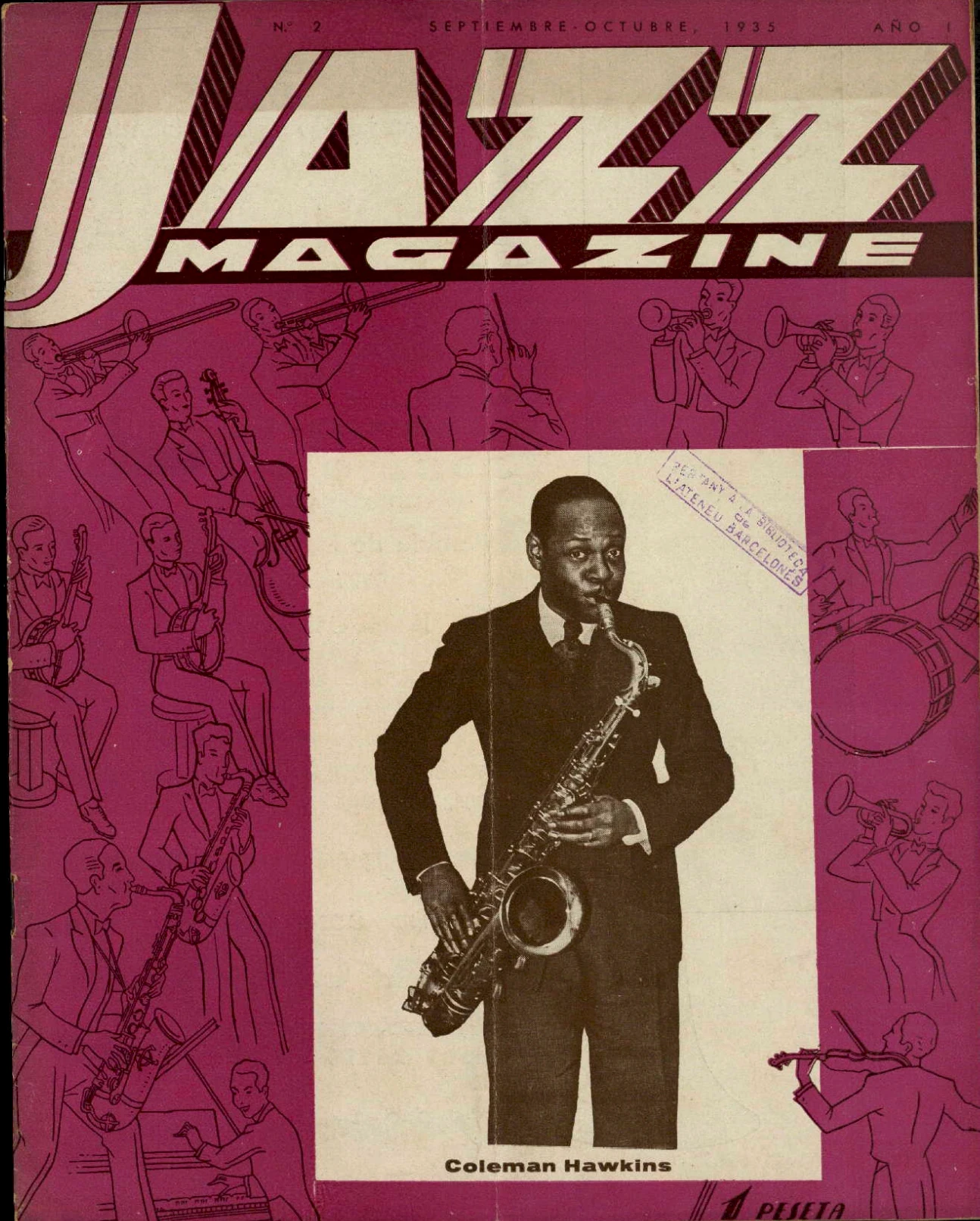

Coleman Hawkins on the cover of Jazz Magazine, Barcelona, 1935

Despite a highly inconspicuous Black presence, for centuries in Spain, racism can be seen to have taken shape in the form of ideologies, portrayals and stereotypes rooted in the modern idea of the enslaved Black man.14 Later, in contemporary times, the notions of African and Black otherness became interwoven with hispanotropicalism,15 with its depiction of Black ‘savages’ who needed civilizing and acculturating, whereas their creations were to be appropriated and their exotic character put on display.16

The centuries-long absence of emancipated Black communities has had serious consequences, leading to a level of defencelessness against Iberian white narratives. Thus, when a circular was sent to radio stations in 1943 to ban jazz as a degenerate form of art, ‘a stultifying and animalistic music, something far removed from our robust racial characteristics’, it was met with no response.17 This is paradigmatic of the relationship then of Blackness with this territory, which gave little room for agency and demanded an absolute compliance with violent acts.

Racial imaginaries have changed little over time, becoming a spiral that perpetuates oppression and relegates the lives of Black people to the margins. The English sociologist Stephen Small, on visiting Madrid in 2010, describes the territory’s relationship with Blackness:

The only Black people I saw, literally, on the streets of Madrid were Black women prostitutes, Black men begging, Black men cleaning the streets, those were the only Black people I saw. And I was like, ‘What is going on here?’18

Up to the second half of the last century, there were no documented efforts by Black people to really unite and confront this disregard and the adversities they all faced, including slavery, colonialism and racism.19 Only in a few specific moments, in the interwar period, for example, can we see cultural activities such as jazz and boxing providing fleeting spaces of visibility and solidarity.

Jazz

Moving on from literature, the reception of jazz in Spain reveals new layers of whitewashing and cultural appropriation. In the summer of 1937, seventeen years before Richard Wright arrived in Spain, Nicolás Guillén and Langston Hughes crossed the same border. They were war correspondents aboard a crowded train on their way to a country at war. The scene was quite different from that which Wright encountered: although there was a war on, jazz was still alive in Spain, with Barcelona at the epicentre. One of the first jazz associations in Europe, the Barcelona Hot Club had been founded two years earlier in 1935. Inspired by the Paris Hot Club, it aimed to raise the profile of jazz as an art form. The Hot Club created a world peopled by critics, collectors, composers, musicians, fans, record companies, publishers, radio stations and film companies. Everything operated under principles of racial exclusion and cultural hierarchy: the Hot Club’s obsession with differentiating and preserving ‘artistic’ and ‘authentic’ jazz from popular jazz in no way signified protecting or respecting Black people, and the legacy of that world persists to this day. Thus, for example, in 1935 the critic Juan Aragonés argued that Black creativity was linked to its infantilism:

And what are the Blacks, if not what connoisseurs have said over and again from time immemorial: big children. Everything, everything, in their art offers this unmistakable sincerity, this purity of expression that we esteem so highly in true popular art, which is also an art for grown ups.20

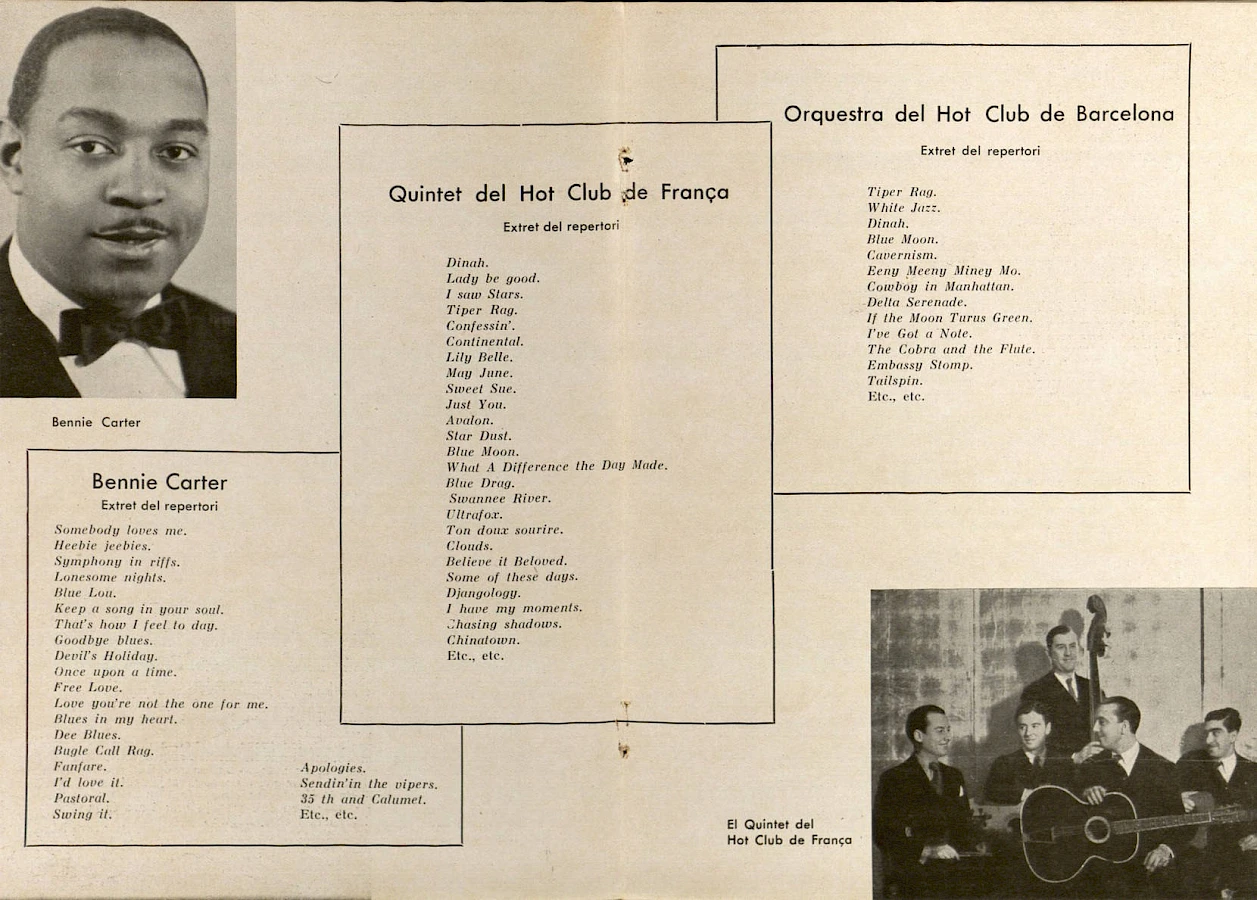

The first concert organized in Barcelona took place in 1936, with a performance by Benny Carter and the Hot Club quintet from France. Guillén and Hughes, like the Black population of Barcelona, were probably oblivious to the existence of the Hot Club, its concerts and its obsession with enjoying ‘real hot music’ as an art form.

Hot Club programme at the Palau de la Música Catalana, January 1936.

Courtesy Centre de Documentació de l’Orfeó Català

In fact, while sitting on Barcelona’s main avenue La Rambla the day after their arrival, Hughes was recognized by a young Black Puerto Rican who worked as an interpreter. He took them to dance in a small club. From Hughes’s description, the place seems to have been the Olympia, one of the spots frequented by Kid Tunero.

The Cuban boxers frequented, daily, with tropical parsimony, three key places. In the morning they went to the Cuban consulate to pick up correspondence. … At aperitif or coffee time, they all went to Carrer Nou de la Rambla, to the Eden or to the adjacent horchatería (tiger nut milk) cellar bar. In the late afternoon, after spending some more time training at the club, they would sit at the tables outside the Teatre Circ Olympia, at Ronda Sant Pau 27.21

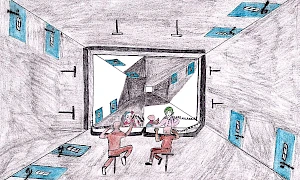

The nightlife spots, however marginal, gave people the chance to meet up. Along with the Olympia, the Eden became a meeting place for the city’s Black population. Musicians, pugilists, artists and dancers of North American, Cuban, Dominican and Puerto Rican origin, as well as from some Black African countries (Guineans, Senegalese and others) met there.22 These bars and clubs were likely spaces of solidarity and exchange, where all the different variants of jazz, but above all hot jazz, were played. The atmosphere would, in all probability, have been very different from the Hot Club, which, while appealing to questions of art, authenticity and genre, stripped jazz of its Black roots and any kind of sociocultural philosophy, reducing it to a depoliticized plaything for the avant-garde.

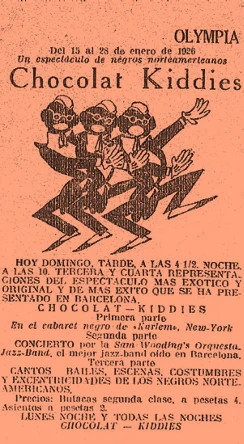

Advertisement for the revue show Chocolat Kiddies, Olympia Theatre, Barcelona, 15–28 January 1926, in Vanguardia (Barcelona), no. 19318, 17 January 1926, p. 18

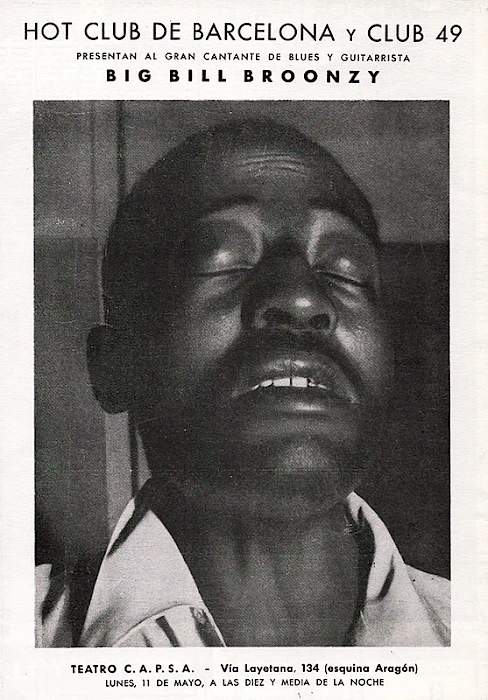

Promotional poster for Big Bill Broonzy at the Hot Club in Barcelona and Club 49. Photograph: Robert Doisneau

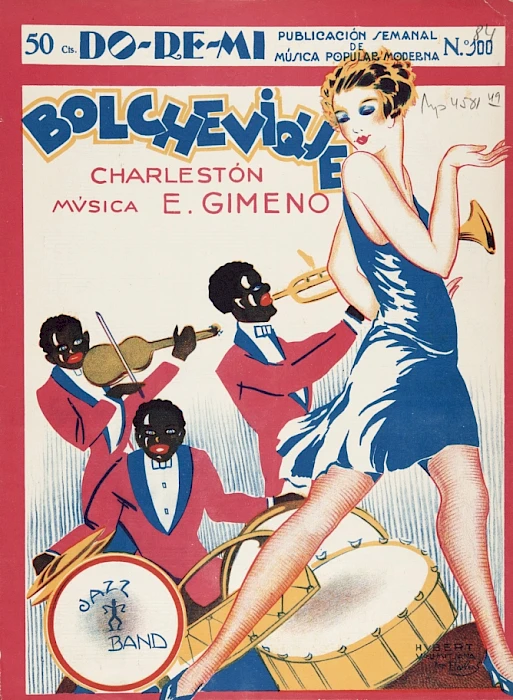

The dysfunctional relationship created here between jazz and Blackness was a strange mixture of fear, indifference, paternalism and appropriation of its forms of creativity, as chronicled by the ways Spanish culture approached jazz in the early twentieth century. Jazz arrived in Spain from the United States after the First World War, via Paris and London. First to land were its popular, avant-garde variants: foxtrot, hot jazz, one-step, shimmy, swing jazz, Charleston, black bottom and blues.23 These styles took off, especially in Madrid and Barcelona; they then developed, evolved, and were discarded in a cycle of consumption marked by an absence of any notable Black presence.

In the context of the 1929 Universal Exhibition, Barcelona became known as the New Orleans of the Mediterranean.24 Throughout the 1920s, Black musicians arrived from the American continent to perform solo or with their bands in nightclubs; Black orchestras that fed the dance fever, such as Los Chocolats Jakson, Harry Fleming’s, Sam Wooding and his Jazz-Band Orchestra (featured in Chocolat Kiddies, above) and Johnny and his Jazz Band, brought in an era of fascination with Black music. Their musicality and energy set off a storm in a country divided between conservative and progressive forces, where a desire for modernity clashed with traditional ideas about morality, collective identity and femininity.25

The dissonance here exemplifies how the response to jazz in Spain was loaded with contradictions. Jazz was celebrated for its vibrancy, but at the same time it reinforced racial stereotypes – and yet again it also played its part in women’s emancipation. Joséphine Baker’s tour of Spain illustrates the ambivalence between fascination and rejection that jazz produced, considered by some parts of society to be an obscene form of music with pronounced sexual elements. A large part of the country, unable to put aside their racial prejudices, projected a view onto jazz that was steeped in exoticism.26

Cover of Do-Re-Mi magazine, featuring Ernest Gimeno’s ‘Bolchevique Charlestón’. Courtesy National Library of Spain

Joséphine Baker in Barcelona at the première of the show Not Yet at the Teatro Cómico (1927–28). Photograph: Merletti

Despite a continued increase in visits by African-American musicians, a deeper understanding of the cultural and political roots of jazz didn’t take hold. Jazz music in Spain is still whitened to this day, estranged from the oral traditions of the cultural environments in which Black music has a specific relationship with the body.27 As the Martinican novelist and essayist Édouard Glissant put it:

The aesthetic form of our cultures must be rooted in oral traditions and jazz, as an expressive form associated with contemporary negritude, represents a subculture and a musical counter-power formed by specific aesthetic components that are connected to Black emancipation.28

Or, as writer and poet LeRoi Jones states:

Jazz is still the music of Negro people, a symbol of Negro cultures that has offered an enhanced way of communication which reaches beyond the power of the spoken or written word, and, with its improvisation and ability to convey emotion, has become a means of expressing the struggle for freedom.29

I would also stress that it has been a means of conveying and expressing the ideas of Pan-Africanism; it connects music with the struggle for racial equality and social justice.

The philosophy of Black music outlined by Glissant and Jones is very different from that of Ramón Gómez de la Serna, who in 1929 appeared in a dinner jacket and in blackface at the Palacio de la Prensa to present Alan Crosland’s film The Jazz Singer (1927). He gave an ambiguous fifteen-minute speech laced with humour that veered between an apology for jazz and racism towards Black people:

There is no need to study the chocolate in their dark soul to get into jazz, since the final reason for it is enough; its notes syncopate the emulation of modern life and it is the shot in the arm that pulls us out of the biliousness of the hustle and rush. It seems that it is causing the European to come around to the sincerity of the negros. As such, those same rhythms may serve him, too.30

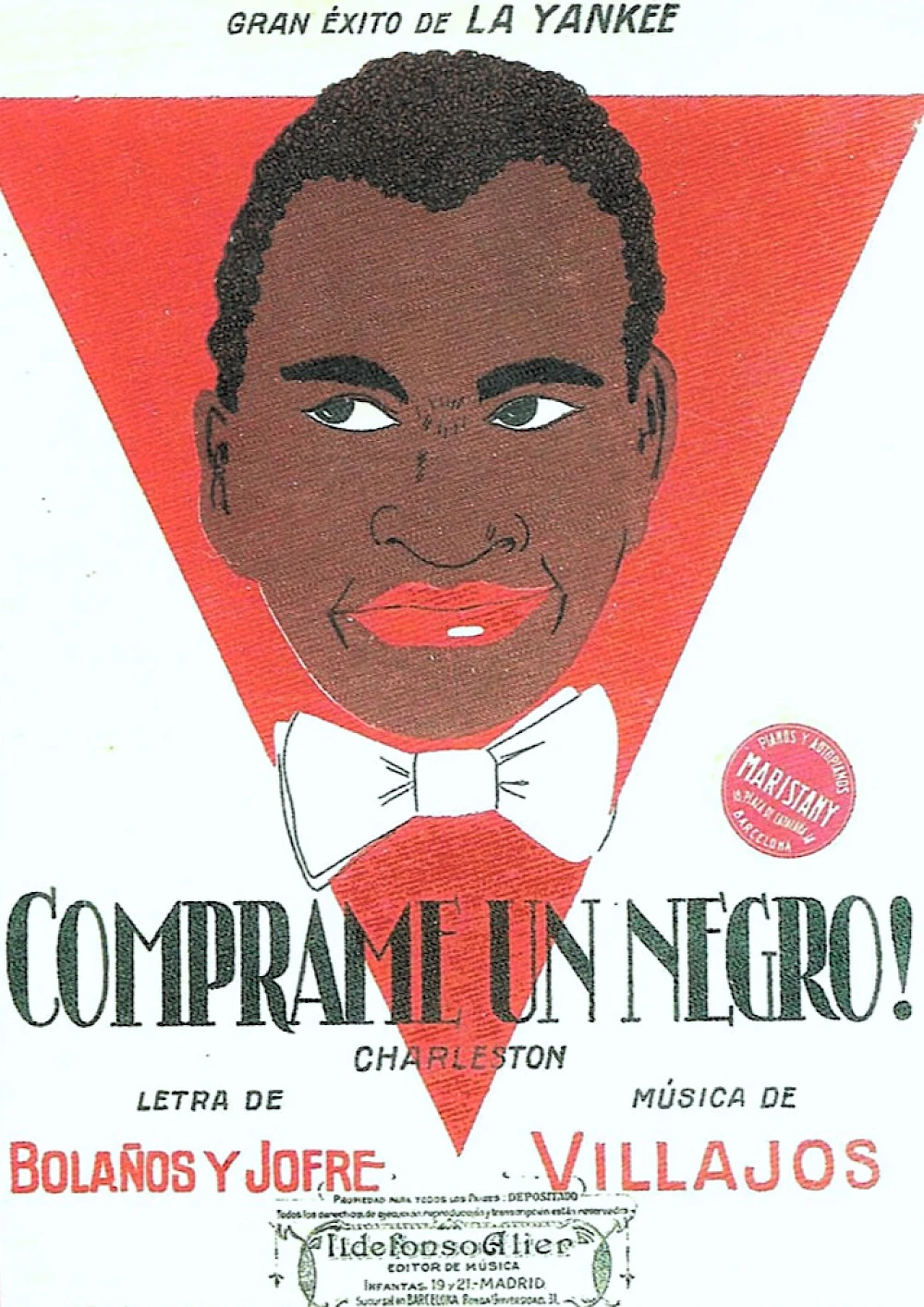

His words show how the European reception of jazz would overlook the cultural, social and political aspect of the people who were creating it. No documented public steps were taken against such reinforcements of racist imaginaries, whether through presentations like that of Gómez de la Serna, comments in the press, or songs such as the popular ‘Madre, cómprame un negro’ by La Yankee, which would later be covered by La Goyita, La Niña de los Peines, Celia Gámez and, finally, Marujita Díaz:

Son tantos negros los que han venido

para enseñarnos el charlestón

que las mamás se ven morás

para evitar ir al bazar,

donde esas muestras de chocolate

a los pequeños hacen exclamar:

«¡Madre, cómprame un negro,

cómprame un negro en el bazar!

¡Madre, cómprame un negro,

cómprame un negro en el bazar!

Que baile el charlestón

y que toque el jazz-band.

¡Madre, yo quiero un negro,

yo quiero un negro para…,

yo quiero un negro para bailar!».

(So many negros have come

to teach us the Charleston

that mamas take great pains

to keep away from the bazaar,

where you find those chocolate samples,

that make their little ones exclaim:

Mother, buy me a negro,

buy me a negro in the bazaar!

Mother, buy me a negro,

buy me a negro in the bazaar!

Let the Charleston dance begin

and the jazz-band play, too.

Mother, I want a negro,

I want a negro to…

I want a negro to dance with!)

Poster for La Yankee’s song ‘Madre, cómprame un negro’ (1929)

Eradication

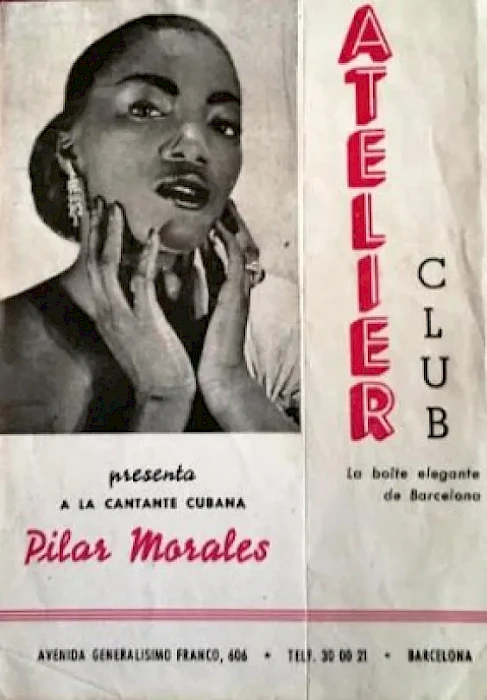

A year before the inauguration of the Hot Club, in November 1934, Música Viva, the first magazine specifically about jazz in Spain, was published.31 In August of the same year, a student from Equatorial Guinea, José María Bakele, published an article in the Heraldo de Madrid newspaper entitled ‘El horror de la civilización en el continente negro’ (The Horror of Civilization on the Dark Continent),32 criticizing the colonial regime. Despite declaring himself ‘a Spanish subject of the negro race, born in this country’, three months later he received notification of his expulsion from Spanish territory, as an ‘undesirable indigenous person’. His reality, like that of many Black people living in Spain, was absolutely alien to the Spanish ‘jazz milieu’, a world that lived with its back to Spanish Blackness. It wasn’t until some years later that Pilar Morales, and later still Guillem d’Efak, a native of ‘this country’, would become the first Black artists to join the Catalan jazz elite.

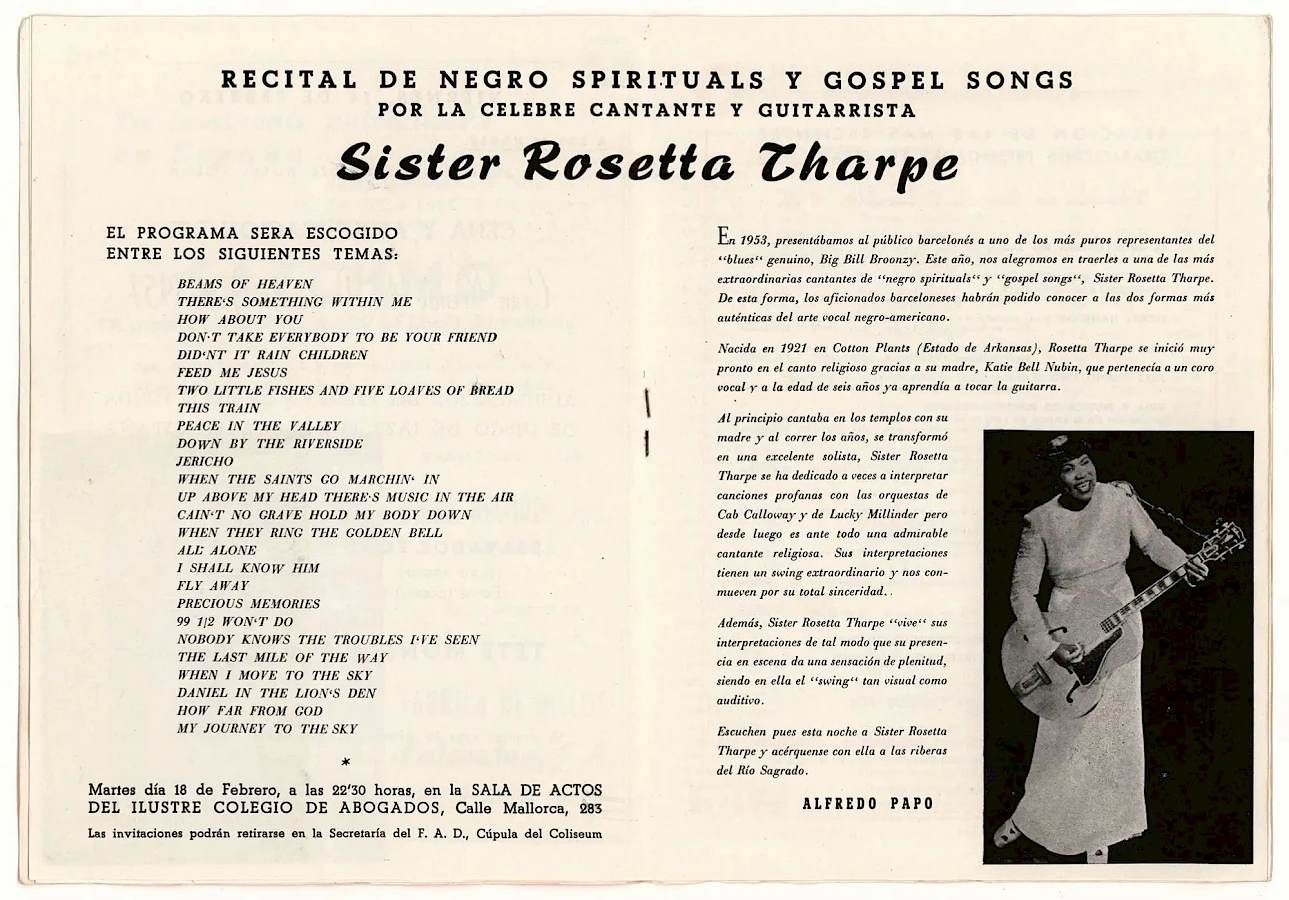

Performance by Sister Rosetta Tharpe featured in the programme of events organized for the 1957 Jazz Record Grand Prix, Barcelona, 1958

Thus, jazz, blues and, to a lesser extent, negro spiritual and gospel music became cult music for the Spanish avant-garde, those belonging to the bourgeoisie and the middle classes. They selected and appropriated the sounds suited to their ideologies, just as in the colonies it was members of white society, i.e., colonists, who validated Black sounds according to their tastes. In a way, this is what LeRoi Jones denounced in his 2013 essay ‘Jazz and the White Critic’, where he wrote that most of the critics were (as they still are) middle-class individuals with privileged cultural backgrounds, and that white musicians had taken over positions that rightfully belonged to Black musicians.

The first serious white jazz musicians sought not only to understand the phenomenon of Negro music, but also to appropriate it as a means of expression which they themselves might utilize. The success of this ‘appropriation’ signalled the existence of an American music, where before there was a Negro music. But the white jazz musician had an advantage the white critic seldom had.33

The same was true in Spain throughout the 1920s and 1930s, because, although jazz music came from, and was initially popular with, the working classes, even then the jazz scene effectively ‘belonged’ to the upper middle classes – those who could collect, travel and hire great musicians. The musical panorama of Spanish jazz was so white that the forms of appropriation of the Black sound were like those that had taken place in the United States, the difference being that in the US there was a Black collective body as well as different forms of Black resistance. Also, there, Pan-Africanism played a significant role.

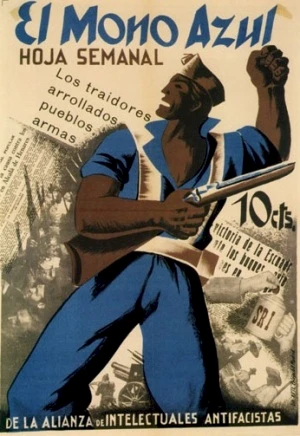

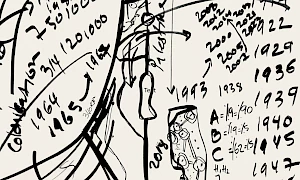

El Mono Azul: Weekly Leaflet (10 cents), The Alliance of Antifascist Intellectuals

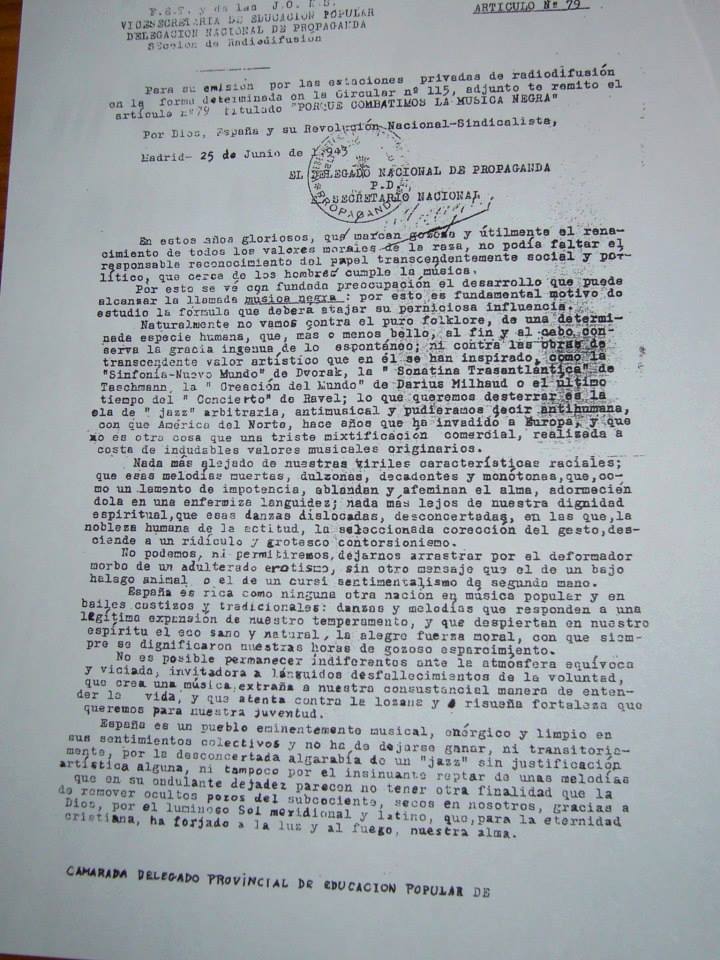

Communiqué banning jazz, signed by the National Propaganda Delegation. The compulsory order was broadcast on the national radio station, Radio Nacional

Babiano poster, ‘Culture is another weapon against fascism’, circa 1936.

Courtesy Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes

In Spain, the political context caused jazz to shift from being a popular genre to avant-garde. More than a few critics and politicians raised their voices to denounce jazz as a racial threat, a form of music whose rhythms perverted the youth. As a result of this the music was banned in Spain, as in other fascist countries such as Germany and Italy. Hitler saw it as degenerate music to be eradicated, and in 1935 the Nazi Minister of Propaganda banned the broadcasting of Judeo-Negro-American music; in 1938, Mussolini’s racial laws did the same in Italy.34 Francoism followed their approach of using culture and music as a way of reconstructing identity. However, jazz remained popular; swing in particular was a panacea for young people during those hard years.35 In the early 1940s, the Francoist government began a media offensive against jazz, which it considered to be against its national values.36 These values defended the Catholic religion as the central pillar of the race, inherent to the Spanish nation. Thus, jazz music was associated with Blackness and with paganism – the antithesis of Spanish music. On 25 June 1943, the National Propaganda Delegation issued a communiqué entitled ‘Porque combatimos la música negra’ (Why we are combatting Black music), with mandatory orders prohibiting all radio stations in the country from broadcasting jazz. The ban remained in force for ten years.

Modern jazz and its derivatives are an abusive preference, not justified even as a pleasant pastime … however much they may deny the art and insist on learning to ‘go native’ to the beat of these exotic black dances, the product of the American jungles. … Spain is an eminently musical people, energetic and clean in its collective feelings, and it must not allow itself to be won over, even temporarily, by the disconcerted hubbub of jazz without any artistic justification.37

In the eyes of the regime, the music was ‘primitive, immoral, wild and effeminate, sung and danced around the bonfire by people with frizzy hair and red lips on a very black mask’.38 For this reason, they also exercised control over periodicals and entertainment through its government agencies.

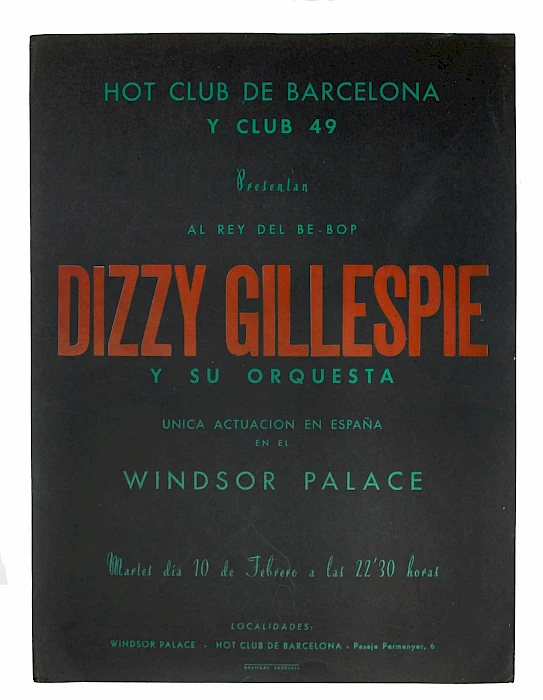

Neither this racist offensive nor the prohibition managed to put an end to jazz. However, it was increasingly stifled until all that remained was an elitist redoubt. This meant that there was hardly any scene by the 1950s, and jazz musicians wanting to forge a career had to leave the country. This was the case with Pilar Morales and Tete Montoliu, who emigrated first to Berlin and then Copenhagen in a bid to make a living from their music.39

Poster advertising Pilar Morales at the Atelier Club

Poster for a Dizzy Gillespie concert at the Windsor Palace in Barcelona, presented by the Hot Club of Barcelona and Club 49, 10 February (1953).

Courtesy Montoliu Morales family collection

During the post-war period, jazz underwent a process of homogenization that persists today. The seeds of a modern-day cultural panorama opposed to difference and variety – a situation actively perpetuated by the media – were sown during those days. It was a time obsessed by the moral revolution, a time of prohibition and the exaltation of the symbols of a unique, superior, Spanish race. This was promoted by the regime through its ordinances, its numerous pedagogical materials, and its films such as Raza (1941), a film based on a novel written by Jaime de Andrade, the pen name of Francisco Franco. This persistence in the creation of a white musicality that scorned Black sounds even reached Equatorial Guinea. Equatoguinean writer and musician Francisco Zamora shares what was heard on Guinean radio in the 1950s:

At home we listened to a bit of everything, Spanish music, but above all Congolese music. Spanish music, because that’s what was played at prime time. For example, the pasodobles [laughs]. It was full-blown colonisation. And the colonist played the music he liked to listen to. That doesn’t mean that there were no spaces dedicated to African music.40

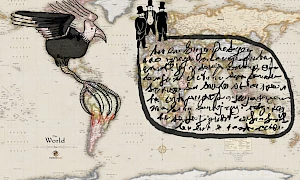

A country fascinated by race, one which operated under xenophobic, religious and patriotic insignia, is what Richard Wright encountered on crossing the Spanish border. After that journey, he argued in Pagan Spain that this genre of ‘paganism’ was the country’s driving force. However, he almost completely failed to perceive the racial project behind it – a project which limited the freedom of Black people and rendered any social confrontation or collective Pan-Africanist struggle impossible. Besides being dispersed, the Black collective body was either depleted or in some cases clinging to survival by participating in the colonizing project – the Black section of the Falangists, the ‘flechas morenos’, and the Guinean wing of the Spanish neo-Nazis being the most radical examples.

However, the majority of the Black population lived in a situation of alienation and censorship, and the struggles and emancipatory projects within Blackness were relegated to the personal, domestic sphere, often limited to individual struggles for dignity and survival. Jazz, its dances, music and lyrics burst onto the scene like sparks of freedom – and then were whitewashed, stripped of their political dimension and turned into entertainment for white consumption. But every note, every gesture of resistance, everybody that would not just disappear left traces that resist this erasure. Taking note of these signs left behind is not just an exercise in recollection: it is about opening up space for a history that is still being written, a history in which the Black voice in Spain no longer remains on the sidelines or in the shadows.

Related activities

-

–MACBA

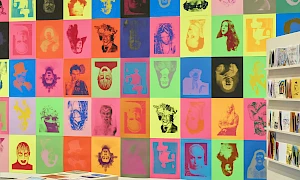

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica

Curated by MACBA director Elvira Dyangani Ose, along with Antawan Byrd, Adom Getachew and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica is the first major international exhibition to examine the cultural manifestations of Pan-Africanism from the 1920s to the present.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–VCRC

Kyiv Biennial 2023

L’Internationale Confederation is a proud partner of this year’s edition of Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

MACBA

Anti-imperialism in the 20th century and anti-imperialism today: similarities and differences

PEI OBERT seminar

Lecture by Ramón GrosfoguelIn 1956, countries that were fighting colonialism by freeing themselves from both capitalism and communism dreamed of a third path, one that did not align with or bend to the politics dictated by Washington or Moscow. They held their first conference in Bandung, Indonesia.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

Maria Lugones Decolonial Summer School

Recalling Earth: Decoloniality and Demodernity

Course Directors: Prof. Walter Mignolo & Dr. Rolando VázquezRecalling Earth and learning worlds and worlds-making will be the topic of chapter 14th of the María Lugones Summer School that will take place at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Archive of the Conceptual Art of Odesa in the 1980s

The research project turns to the beginning of 1980s, when conceptual art circle emerged in Odesa, Ukraine. Artists worked independently and in collaborations creating the first examples of performances, paradoxical objects and drawings.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–MACBA

Song for Many Movements: Scenes of Collective Creation

An ephemeral experiment in which the ground floor of MACBA becomes a stage for encounters, conversations and shared listening.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

HDK-Valand

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

Moderna galerija

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

WIELS

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

–

Kyiv Biennial 2025

L’Internationale Confederation is proud to co-organise this years’ edition of the Kyiv Biennial.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

WIELS

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels. Rana Issa and Shayma Nader

Join us at WIELS for an evening of fiction and poetry as part of L'Internationale Online's 'Collective Study in Times of Emergency' publishing series and public programmes. The series was launched in November 2023 in the wake of the onset of the genocide in Palestine and as a means to process its implications for the cultural sphere beyond the singular statement or utterance.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Study Group: Aesthetics of Peace and Desertion Tactics

In a present marked by rearmament, war, genocide, and the collapse of the social contract, this study group aims to equip itself with tools to, on one hand, map genealogies and aesthetics of peace – within and beyond the Spanish context – and, on the other, analyze strategies of pacification that have served to neutralize the critical power of peace struggles.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Near East, Far West. Kyiv Biennial 2025

The main exhibition of the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, titled Near East, Far West, is organized by a consortium of curators from L’Internationale. It features seven new artists’ commissions, alongside works from the collections of member institutions of L’Internationale and a number of other loans.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: The Brighter Nations in Solidarity: Even in the Midst of a Genocide, a New World Is Being Born

PEI Obert presents a lecture by Vijay Prashad. The Colonial West is in decay, losing its economic grip on the world and its control over our minds. The birth of a new world is neither clear nor easy. This talk envisions that horizon, forged through the solidarity of past and present anticolonial struggles, and heralds its inevitable arrival.

-

–M HKA

Homelands and Hinterlands. Kyiv Biennial 2025

Following the trans-national format of the 2023 edition, the Kyiv Biennial 2025 will again take place in multiple locations across Europe. Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) presents a stand-alone exhibition that acts also as an extension of the main biennial exhibition held at the newly-opened Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN).

In reckoning with the injustices and atrocities committed by the imperialisms of today, Kyiv Biennial 2025 reflects with historical consciousness on failed solidarities and internationalisms. It does this across an axis that the curators describe as Middle-East-Europe, a term encompassing Central Eastern Europe, the former-Soviet East and the Middle East.

-

HDK-Valand

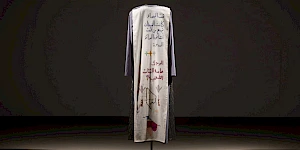

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

–

Everything for Everybody. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Everything for Everybody’ takes place in the Ukraine, at the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture.

-

–

In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture’ takes place at the Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv.

-

MACBA

School of Common Knowledge: Fred Moten

Fred Moten gives the lecture Some Prœposicions (On, To, For, Against, Towards, Around, Above, Below, Before, Beyond): the Work of Art. As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA presents this lecture on artworks and art institutions in relation to the challenge of blackness in the present day.

-

–MACBA

Visions of Panafrica. Film programme

Visions of Panafrica is a film series that builds on the themes explored in the exhibition Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, bringing them to life through the medium of film. A cinema without a geographical centre that reaffirms the cultural and political relevance of Pan-Africanism.

-

MACBA

Farah Saleh. Balfour Reparations (2025–2045)

As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA is co-organising Balfour Reparations (2025–2045), a piece by Palestinian choreographer Farah Saleh included in Hacer Historia(s) VI (Making History(ies) VI), in collaboration with La Poderosa. This performance draws on archives, memories and future imaginaries in order to rethink the British colonial legacy in Palestine, raising questions about reparation, justice and historical responsibility.

-

MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica OPENING EVENT

A conversation between Antawan I. Byrd, Adom Getachew, Matthew S. Witkovsky and Elvira Dyangani Ose. To mark the opening of Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, the curatorial team will delve into the exhibition’s main themes with the aim of exploring some of its most relevant aspects and sharing their research processes with the public.

-

MACBA

Palestine Cinema Days 2025: Al-makhdu’un (1972)

Since 2023, MACBA has been part of an international initiative in solidarity with the Palestine Cinema Days film festival, which cannot be held in Ramallah due to the ongoing genocide in Palestinian territory. During the first days of November, organizations from around the world have agreed to coordinate free screenings of a selection of films from the festival. MACBA will be screening the film Al-makhdu’un (The Dupes) from 1972.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Cinema Commons #1: On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes

On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes is a Museo Reina Sofía film programme overseen by Miriam Martín and Ana Useros, and the first within the project The Cinema and Sound Commons. The activity includes a lecture and two films screened twice in two different sessions: John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001).

-

–

Vertical Horizon. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Vertical Horizon’ takes place at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, at the initiative of tranzit.at.

-

–

International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People: Activities

To mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People and in conjunction with our collective text, we, the cultural workers of L'Internationale have compiled a list of programmes, actions and marches taking place accross Europe. Below you will find programmes organized by partner institutions as well as activities initaited by unions and grass roots organisations which we will be joining.

This is a live document and will be updated regularly.

-

–SALT

Screening: A Bunch of Questions with No Answers

This screening is part of a series of programs and actions taking place across L’Internationale partners to mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People.

A Bunch of Questions with No Answers (2025)

Alex Reynolds, Robert Ochshorn

23 hours 10 minutes

English; Turkish subtitles -

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Until Liberation: A Collective Reading and Listening Session by Learning Palestine

PEI Obert presents a collective session with Learning Palestine. At this historical juncture – amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the censorship and repression of all things Palestinian – Learning Palestine invites us to gather not only in refusal but also in affirmation.

Related contributions and publications

-

Introduction, Living with Ghosts

Nick Aikens, Jyoti Mistry, Corina Oprea -

On White Innocence

Gloria Wekker -

Black Atlantis: the Plantationocene

Ayesha Hameed -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

The Kitchen, an Introduction to Subversive Film with Nick Aikens, Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi

Nick Aikens, Subversive FilmSonic and Cinema CommonslumbungPast in the PresentVan Abbemuseum -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Rewinding Internationalism

InternationalismsVan Abbemuseum -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Veil of Peace

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuPast in the Presenttranzit.ro -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale ConfederationEN caInternationalismsStatements and editorials -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay PrashadInternationalismsSonic and Cinema Commons -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Present Present Present. On grounding the Mediateca and Sonotera spaces in Malafo, Guinea-Bissau

Filipa CésarSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the Present -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

S come Silenzio

Maddalena FragnitoEN itInternationalismsSituated Organizations -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cinq pierres. Une suite de contes

Shayma NaderEN nl frInternationalisms -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Alissar SeylaInternationalisms -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Today, again, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalisms -

Isabella Hammad’ın icatları

Hazal ÖzvarışEN trInternationalisms -

To imagine a century on from the Nakba

Behçet ÇelikEN trInternationalisms -

Internationalisms: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardInternationalisms -

Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

İrem GünaydınInternationalisms -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials -

Poetry Against Language Dioxide

Rana IssaInternationalisms -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations