Some Things We Learnt: Working with Indigenous culture from within non-Indigenous institutions

Curators Pablo Lafuente, Sandra Ara Benites and Rodrigo Duarte have worked with indigenous communities in Brazil on a number of exhibiton and institutional projects since 2017. The following text, first presented as part of Climate Forum IV 'Our world lives when their world ceases to exist’, offers a series of critical insights and reflections into what it means to work with Indegenous communities in non-Indigenous institutions.

Over the past decade, art and cultural institutions in Brazil have developed a strong interest in Indigenous culture, a shift of focus that contrasts sharply with the lack of attention over the previous ten years. This shift happened in response, first and foremost, to a direct demand for access, agency and representation by Indigenous peoples and collectives, which in turn resulted from the intensification of Indigenous organizational processes in the struggle for rights and for the demarcation and legal recognition of Indigenous lands since the 2000s. After an initially lukewarm response from most institutions and the professionals working within them, a new willingness to respond to these demands emerged, eventually leading to invitations to artists, and to small- and large-scale exhibition projects. But the entry of Indigenous themes and individuals into art institutions was often not only mixed up with narratives and agendas that are not central to the Indigenous movement – for example, sustainability and/or the climate emergency, framed as issues that Indigenous communities should help solve – but also accompanied by urgencies, epistemological assumptions and working practices and processes that are rarely negotiated by, or negotiable for, these institutions.

Consequently, we can say that Indigenous presence has never been so significant in Brazil’s cultural-institutional context, both as a topic and because of the number of people involved, almost exclusively artists; yet at the same time, it seems that this incorporation is simply that: an incorporation that assimilates Indigenous people and cultural practices into established institutional models, with no apparent willingness to reconsider assumptions, concepts, values and processes that may hinder the capacity of institutions, and the people working within them, to meet Indigenous demands with responses of the breadth and depth they deserve.

Thus, it happens that individuals who are able to operate as the art system requires – in terms of their availability for projects conceived by others, their mobility and production processes – are those who (always temporarily) gain access and visibility. The practices that are accepted are almost exclusively individually authored, object-based and commercializable, and artists’ work is remunerated according to classic post-Fordist processes. As such, the way in which the art system incorporates and assimilates Indigenous artists reveals how cultural production models ignore and override the initial aims of the approach, namely to contribute to sustaining ways of life that differ from, or offer alternatives to, the system that non-Indigenous people inhabit and reproduce.

We, the authors of this text, are also part of this process. Over the past ten years, we have worked in this intermediary terrain of negotiation, organizing curatorial projects and discussion-based programmes focused on Indigenous issues and Indigenous people, developed for non-Indigenous cultural institutions (museums, art centres, cultural agencies). Among these projects are the exhibition and conversation series Dja Guata Porã: Rio de Janeiro indígena (2016–17) at the Museu de Arte do Rio, Rio de Janeiro, curated by Sandra Ara Benites, José Bessa, Clarissa Diniz and Pablo Lafuente; 1 the seminar Episódios do Sul (2017) at the Goethe Institut, São Paulo, organized by Ailton Krenak, Suely Rolnik and Pablo Lafuente; the conversation cycle Sawé: Liderança indígena e a luta pelo território (2018–20) at Sesc Ipiranga, São Paulo (a related exhibition of the same name, curated by Sandra Ara Benites, Naiara Tukano, Mauricio Fonseca and Pablo Lafuente, that was scheduled to open in April 2020 was then cancelled due to the Covid-19 pandemic); 2 the Jaraguá Guarani project initiated by Funarte in 2024 and coordinated by Sandra Ara Benites and Pablo Lafuente; the 2024–27 project Pororoca* Water Cosmo-technologies curated by Sandra Ara Benites, Walmeri Ribeiro and others at the Goethe Institut/Humboldt Forum;3 and the 2025–26 exhibition Indigenous Insurgencies at Sesc Quitandinha, Petrópolis, curated by Sandra Ara Benites, Marcelo Campos and Rodrigo Duarte.4

The reflections that follow result from our experience as cultural agents and serve, first and foremost, as notes of caution to ourselves, in relation to the work we have done so far. Perhaps they might also be useful for others wishing to work with Indigenous culture from within or alongside non-Indigenous institutions.

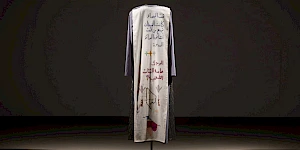

'Dja Guata Pora: Rio de Janeiro indígena’, Museu de Arte do Rio, Rio de Janeiro (2016-17), installation view

'Dja Guata Pora: Rio de Janeiro indígena’, Museu de Arte do Rio, Rio de Janeiro (2016-17), installation view

'Dja Guata Pora: Rio de Janeiro indígena’, Museu de Arte do Rio, Rio de Janeiro (2016-17), installation view

'Dja Guata Pora: Rio de Janeiro indígena’, Museu de Arte do Rio, Rio de Janeiro (2016-17), installation view

'Insurgências indígenas’, Sesc Quitandinha (2025), installation view

'Insurgências indígenas’, Sesc Quitandinha (2025), installation view

1. Listening as a foundation: listening while building trust

When we speak of listening as a foundation, we refer to actively seeking to understand meanings and intentions according to the logic of what the community or people involved in the project are trying to convey. When an institution arrives in a community or village through a cultural project such as an exhibition, it is essential to communicate the project’s intentions and clarify the objectives being pursued. If the institution aims to create dialogue with the community and welcome its demands, it must communicate why that dialogue is desired. Often, institutions arrive with ideas constructed outside the community rather than from within it, and throughout the process this can lead to situations of conflict. By conflict, we mean situations in which a community may disagree over something that previously had not been part of its horizon of debate or its everyday reality. Before even formulating a project, institutions need to reflect on what the needs and demands of that community might be and to consider whether those demands can truly be addressed within that exhibition or that institution.

The moment of listening is only one moment within the dialogue of institutions, or institutional workers, with communities; nor is listening limited to hearing the words that are spoken. Listening means understanding the community’s demands and discerning what can be materialized in an exhibition, as well as how that could be organized, mobilized and implemented within the community.

During the organization of the exhibition Dja Guatá Porã, the Pataxó people were engaged in the reoccupation of territory in Iriri, on the coast of the state of Rio de Janeiro, and were deeply concerned with discrimination and racial violence as well as with the urgency of occupying and demarcating their land. The Pataxó brought these concerns to the museum’s team so that they would be considered within the curatorial process. Based on this listening, we, as curators, actively sought partnerships that could address the issue of their territory. In theory, this is a matter that would not conventionally fit within an exhibition at that art museum, but we incorporated this demand into the project so that the community could receive support for their fundamental territorial claims. Through active listening and open, constructive dialogue, it became possible to articulate an institutional interface with the Public Defender’s Office, going on to conduct a mapping that supported the Pataxó people’s territorial claims in Rio de Janeiro.

Listening cannot merely be a procedural or static act, but rather a movement that mobilizes community demands, horizons and information through direct dialogue and the building of trust with that community. Trust is grounded in listening and dialogue. This process also helps shape paths of mediation and negotiation. The considerations of a curatorial approach that arises from such dialogue are woven out of what is collectively built through hospitality, encounters, partnership and continuity. Part of creating relationships of trust means being and staying together with communities beyond personal or institutional interests and the immediate limits of specific projects.

Extractivist practices of capturing and appropriating traditional knowledge, with no intention of returning to communities after a project or exhibition has been completed, are to be avoided at all costs – yet many institutions still operate by collecting information from local communities and disappearing with it, as if it were raw material to be processed for presentation in an exhibition without connection to the territory where it was generated. They conceive a project, seek out Indigenous peoples or traditional communities, collect information which then evaporates into the institutional sphere, reappearing, transformed, in the form or context of an exhibition.

Exhibition projects with Indigenous peoples must, rather, operate with a perspective of continuity that makes it possible to establish and maintain relationships of trust. In the project Pororoca* Water Cosmo-Technologies, for example, the curatorial project of Nhande Rape Ysyry, emphasized building trust with and between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities by engaging with relationships to water.

Commitment to the process requires engagement in conciliations that help maintain trust. A trustworthy relationship is one in which the community welcomes and is welcomed in return, enabling the sharing of traditional knowledge. It is a way of contributing to Indigenous communities, helping to defend their rights, and ensuring the continuity and contemporary relevance of their knowledge. It is a commitment to leaving a legacy or at least a contribution, guaranteeing some kind of return to the community once the project is done.

2. Individual and collective agency: art and artists

Indigenous artists, broadly speaking, work collectively. We call an individual artist someone who has the skill to create and produce certain objects: someone who knows how to carve small wooden animals like a tatu (armadillo) or a jaguar, for example, carving, creating, working with his or her hands; and the more they practice, the more they develop their skill and creativity. The same applies to someone who knows how to weave baskets. Among the Guarani, some women and men can make very small and perfectly crafted baskets, while others have less skill. This is what we call ‘the artist as an individual’. But the knowledge that this artist carries in order to produce the object is already collective.

For example, when a Guarani artist searches for wood to carve a wooden figure, they must go through a process of asking permission from the spirits. Upon entering the forest to retrieve wood, it is necessary to ask permission from the spirits of that place, from the plants, from the trees. The same applies to the river: when someone goes to bathe or enter the water, they must also ask for permission from the river spirits. And when planting, one must ask for permission from the spirits before clearing; and at harvest time, the karaí ritual, the blessing of the harvest, is performed.

All this is part of the collective, of collective knowledge. So the process of carving wood, obtaining materials, creating the figure involves knowledge that comes from the collective. This is why an Indigenous person is never just an individual. As an artist they are an individual, but at the same time they are part of a collective that creates the knowledge that sustains the creation of such objects. So, it is important to consider both dimensions: when we speak of Indigenous art, we must understand that it does not come solely from an individual, nor solely from the collective. It emerges from the relationship between the two.

In Indigenous worldviews – and here we are not speaking only of a single people, such as the Guarani, Kaingang or Pataxó, but of Indigenous peoples at large – art is always connected to cosmologies and cosmovisions. It reflects how each people understands the origin of the world, how they relate to the land, to plants, to animals, to humans and nonhumans. Its connection with all that exists is what gives meaning to Indigenous art. All Indigenous populations share this perspective, even if each has its own way of expressing it. It comes from a deep relationship with the land and with the beings that inhabit it.

This understanding of art is very different from that of the juruá (non-Indigenous person). For the juruá, art is often linked to visual aesthetics, to form, to beauty. For Indigenous peoples, aesthetics has another meaning. For example, for a Guarani man, aesthetics lies in knowing how to relate to all beings around him – men, women, humans, nonhumans. It means understanding the worlds of each, recognizing that all are part of a whole, and that coexistence is based on contributing and complementing, not competing.

When an institution expects an Indigenous artist to behave like a non-Indigenous artist by separating him or her from the collective, or applies its own production or market logic, it ignores what is specific to Indigenous art.

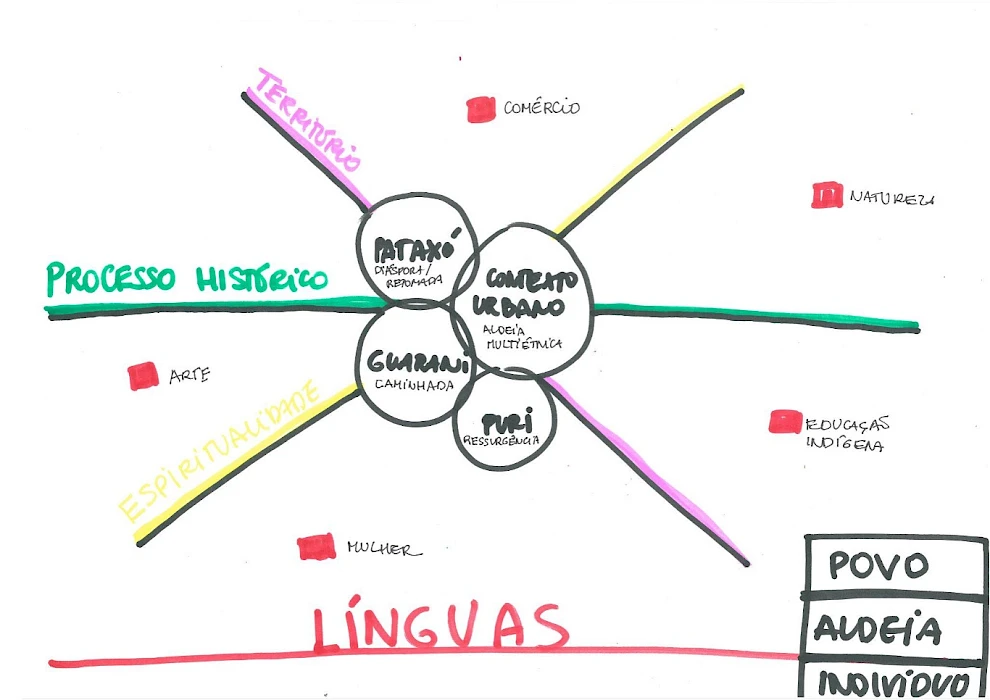

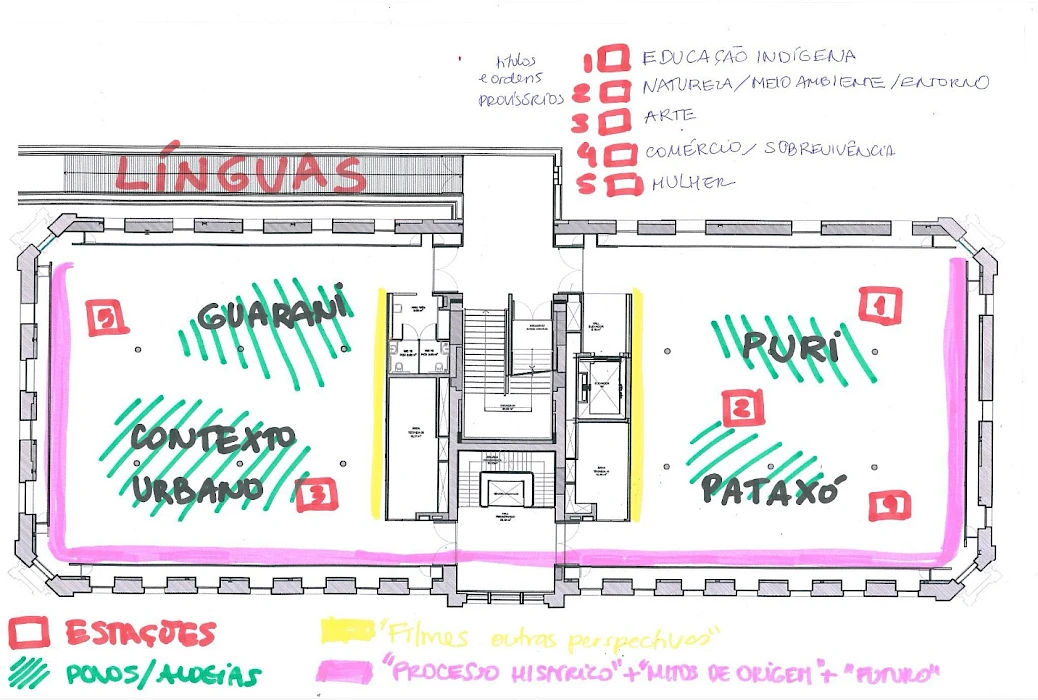

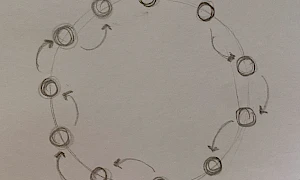

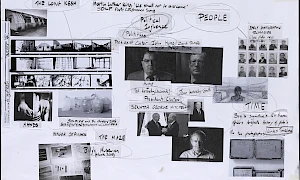

Preparatory drawings for 'Dja Guata Pora: Rio de Janeiro indígena’, Museu de Arte do Rio, Rio de Janeiro

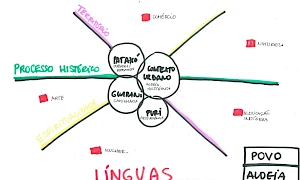

3. Diversity of peoples and territories, from urban contexts to villages

The distributed presence of Indigenous people in both urban and village contexts is the result of the invasion of what is known today as Brazil. Many peoples were forced to leave their original territories, and others left in order to survive. The resulting dispersal is directly linked to resistance, but also to the processes of populational mixing that emerged from it. It is important to remember that the majority of Brazilian territory was once Indigenous territory. What we now call ‘city’ was once ‘Indigenous village’. Many groups resisted as collectives, but others were expelled or displaced to new areas. In many cases, so-called ‘Indigenous occupations’ or ‘urban villages’ were not created by the Indigenous people who originally lived there but emerged from processes of expulsion and reorganization. Many groups left and continued their lives elsewhere, while others remained in cities out of necessity. In this process of invasion, it was not Indigenous peoples who came to the city; it was the city that invaded the village.

Today, when Indigenous communities fight for existence and recognition, they demarcate their place, declaring from where they speak: from the city, from the village, from the community. Some communities still use their Indigenous languages, while others were forbidden from speaking them, as is the case of the Pataxó Hãhãhãe, who live in their own villages but lost their language due to prohibition policies. There were many attempts to eliminate Indigenous peoples: by prohibiting languages, invading territories, dispersing communities and forcing populations to mix. Many Indigenous women married non-Indigenous men. The identities of children who grew up in this context were transformed. From this process, new villages and new ways of existing emerged. To this day, it can be difficult to recognize Indigenous people living in cities. Many people do not understand this historical process and assume that the Indigenous person came to the city, when in fact it was the city that came and invaded Indigenous land.

For this reason, we need to be clear: this is a profound and historical issue tied to invasion and resistance. When we speak of representation, we must consider this broader political field. For Indigenous peoples, representation does not only mean debating public policies directed at them. It means being recognized as Indigenous – not white, not Black; it means the recognition of Indigenous existence, history and territory. It is a delicate issue, but also essential to understanding the struggle and presence of Indigenous peoples in Brazil today.

Every process of working with Indigenous culture within cultural institutions must acknowledge this history and incorporate both the diversity of experiences among different Indigenous peoples: their specific cosmovisions; their histories as village-based or urban-based peoples; and these violences that form part of their history, and Brazil’s. This needs to be the foundation of all work, of all choices and interactions, ultimately defining what needs to be done in each project or exhibition.

4. Function and Purpose

The works that Indigenous people produce for exhibitions are a form of provocation-as-education: pedagogical provocations aimed at updating and revising knowledge about Indigenous peoples. What juruá or non-Indigenous people call contemporary art is a way for Indigenous peoples to position themselves politically, to bring visibility to their struggles. When Indigenous works appear in an exhibition, they instantiate, amplify and make visible the provocations of Indigenous peoples.

Institutions must avoid the trap of treating Indigenous artwork as something exotic, romanticized or fetishized – because that is not what it is. They must approach it with care, looking from multiple angles, seeking to understand through it what is important to the community. What is important to debate? What provocations should these artworks bring? Issues related to territory, to cosmovision, to Indigenous knowledge, to the situation of communities living in this territory or that city: the presence of such works in exhibition spaces necessarily makes these spaces places of discussion, debate and provocation. Without such discussion, the artwork loses part of its function.

If the function of the artwork is to prompt discussion and debate, then projects with Indigenous communities (whether they include contemporary Indigenous art or more traditional practices) must be the result of negotiation – starting with the process of listening with, and from which, these notes began. The institution’s preconceived ideas about formats and objectives cannot be conceived in ways that do not allow change. The eventual format resulting from such listening and negotiation may ultimately satisfy the institution and meet its needs, but what the institution wants or needs cannot be the priority. Nor can it be intransient: we must always strive to understand in good faith whether what the institution wants is compatible with a history and a reality that goes far beyond its walls.

Translation from Portuguese to English by Rodrigo Duarte.

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

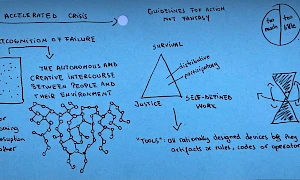

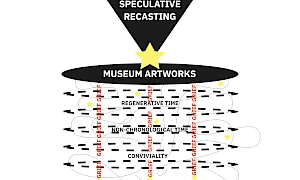

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Some Things We Learnt: Working with Indigenous culture from within non-Indigenous institutions

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteLand Relations -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations