The Inventions of Isabella Hammad

In this review, journalist Hazal Özvarış offers a close reading of British-Palestinian author Isabella Hammad’s novels The Parisian (2017) and Enter Ghost (2023). Drawing on the narrative techniques Hammad employs, Özvarış addresses the potential of fiction to reflect the complexities of Palestinian existence under occupation and weave Palestinian history into contemporary realities within the context of the ongoing genocide.

It starts with a play. A play within a play. It starts with somebody going onstage, someone who’s fed up with life, who wants to commit suicide. And then … the lights go out. … So the director comes out with a flashlight, and he says, Please excuse us, we just need some time and we’ll fix the lighting, and then we’ll go on with the play. And the whole play is the audience waiting for the lights to come back on, and the director trying to find someone in the audience to fix the electricity. And in the beginning the audience thinks this is a real power cut. The actors are spread out, and they start acting from their different positions. … Everyone gets on the stage to show that he or she is trying to fix the thing, but they don’t do anything, they just want to show off. … in the end, the lights come back on. Because a worker, a carpenter, he’s the only one who goes onstage and works silently, without talking. And he fixes the electricity. But he also gets electrocuted and dies. And the question becomes, whose responsibility is that?1

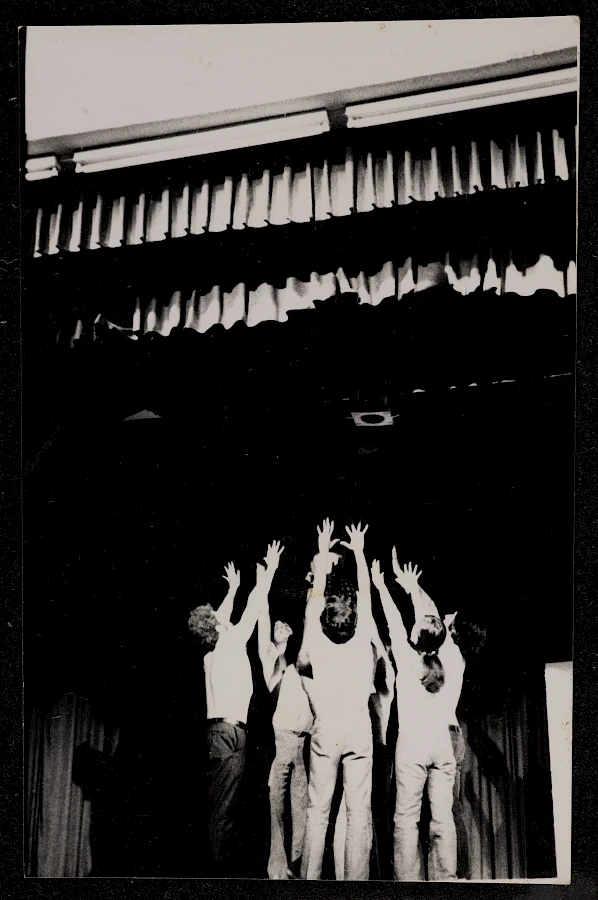

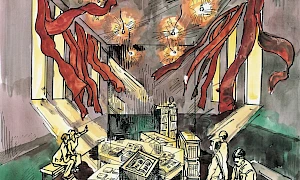

A scene from the play Al-Atma (‘Darkness’) performed by the Balalin troupe, September – December 1972. Courtesy The Balalin Troupe Collection, Palestinian Museum Digital Archive, palarchive.org

Al-Atma (‘Darkness’) is one of the most striking plays of the 1970s, the golden age of Palestinian theatre. According to Isabella Hammad, who mentions the play in more detail than I have quoted here in her most recent novel, ‘Darkness’ – staged four times by the Balalin (Balloons) troupe – ends with the cast and the audience collectively illuminating the stage with candles in their hands.2 The darkness they create allows the actors to speak about different forms of oppression, such as occupation and patriarchy, without seeking to lift the audience out of the darkness they happen to be living in together.

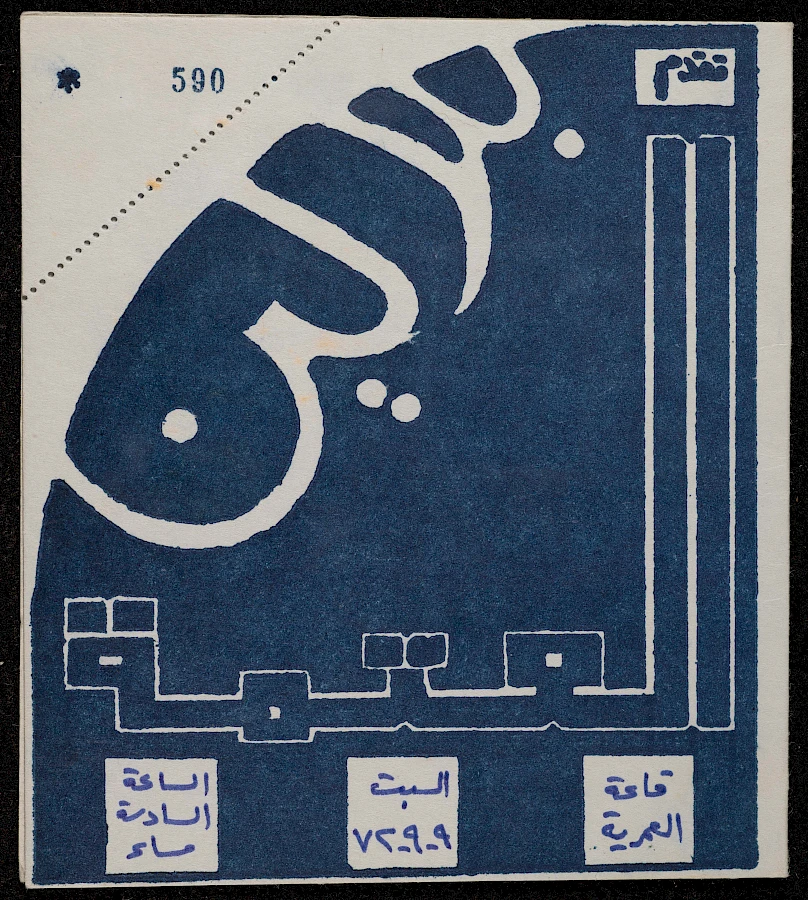

A ticket to attend the play Al-Atma (‘Darkness’) by the Balalin troupe, Jerusalem, 9 September 1972. Courtesy The Balalin Troupe Collection, Palestinian Museum Digital Archive, palarchive.org

In contexts where violence continues uninterrupted for years, both conduct and institutions are shaped by that violence, while the ability to make what is witnessed appear unreasonable is constantly challenged and discredited. Such circumstances render inventions necessary to explain what one experiences not only to others but also to one’s self, and when the issue is Palestine, the bar is set so high that one must also pass through the measure of humanity. This is why the works of Palestinian artists do more than reflect mastery of their chosen art forms; they reveal a clear mind sharpened by experience, a strong sense that the work is created first and foremost as an act of existence, and a look that returns the viewer’s gaze.

That’s the kind of work The Parisian is – Hammad’s debut novel, published in 2017. In her attempt to confront Palestine’s history, to depict the Nakba and its violence that echoes into the future, she envisions a time untouched by such violence. Thus, as we read The Parisian, we are introduced to an old Palestine anew.

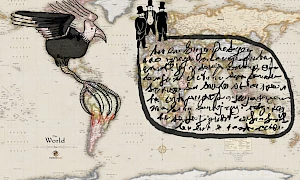

The novel took five years for Hammad to write, in which she recounts her great-grandfather Midhat Kamal’s twenty-year journey. In researching a period for which most witnesses have passed away, Hammad notes that conversations with older generations of Palestinians often drifted towards nostalgia, focusing not on certain details or personal losses, but on landscapes – for instance, olive trees. In the novel, where she weaves historical gaps with fiction, Kamal is sent to France in 1915 by his merchant father to study medicine. He falls in love with France, and with the daughter of an anthropology professor at whose home he resides, while discovering how, in the eyes of his landlord and colleagues, he is synonymous with primitiveness. And when he returns to Nablus in 1919 – a city now within the borders of the West Bank – he finds that Palestine, which he left under Ottoman rule, is under British occupation. Distant from his peers, resentful of his father, yearning for France, obsessed with fashion, and trapped in an unhappy marriage, Midhat leads a life far removed from being a charismatic protagonist. Meanwhile, newspapers read aloud in coffee shops, missionaries, independence movements in the region, particularly in Syria and Iraq, rising Palestinian nationalism, and growing Zionism gradually shift from the background into the forefront.

In this way, Hammad rejects presenting the reader with a stark before-and-after narrative of Disaster, while pointing towards the forces that laid the groundwork for such a rupture. At the top of the list are the dehumanization of the other and British colonialism, while reading about this historical period in Turkey makes one question how the tracks the British followed in the region had once belonged to the Ottomans. Hammad recalls what the Ottoman regime did to the Armenians and the Palestinians fleeing the executions ordered by Djemal Pasha, one of the architects of the genocide. By touching upon the continuities between the two colonial regimes and the disillusionments they left behind, she hints at how Palestinians perceived the Ottoman Empire. Thus, as the author tries to liberate her imagination from the framework constructed by the colonialist,3 the reader comes to grasp a past denied, and Disaster begins to materialize in its absence.

At the end of the novel, Hammad dispels the fantasies Kamal has developed about France. When asked in an interview about her own obsessions, she replies: ‘When you don’t grow up in Palestine, Palestine becomes a – maybe problematically – imaginary place,’ and adds, ‘ … if, after lots of idealizing and nostalgia a Palestinian from outside does manage to go back, the reality of the situation can be a bit of a shock.’4

Although she did succeed in returning from the outside, Hammad is a writer grounded in a Western education. She completed her formal education at Oxford, then at Harvard and New York universities, studying English Literature and Creative Writing, and now, she is living in the US, having received a fellowship from the New York Public Library. With her mastery of the genre (and with the likely impact of her measured approach in line with contemporary literary standards), her first novel quickly gained international recognition. Hammad states that she is often asked whether her aim in writing about Palestine in English is to ‘educate Westerners.’ In her 2023 Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture, she described this assumption as ‘reductive and kind of undignified,’ adding: ‘I like this idea of breaking into the awareness of other people by talking candidly among ourselves.’5 This approach, inspired by feminist activists in Egypt – who, rather than toiling away to educate men about violence against women, prioritize dialogue and solidarity among women – becomes even more pronounced in her second novel.

In Enter Ghost, published about six months before 7 October 2023, Hammad tries to reckon with the feeling of being an outsider caused by the occupation. In an interview she gave long before the book’s publication, she communicates the feeling that she was seeking an answer to the following questions: ‘Where exactly is the inside? We say inside to refer to Palestinians living in 48, but I’m sure they experience their fair share of feelings of being outside. What about Gazans, are they locked in or locked out? Both, I suppose; that’s partly what it is to be imprisoned.’6 To look at today’s violence and the ruptures it produces in relationships, Hammad once again resorts to a measured invention, this time circulating a text across geographies and languages.

Placing Shakespeare’s Hamlet at the centre of her novel, as reflected in its title, Hammad weaves together different, at times conflicting, contemporary experiences of being Palestinian through a theatre company attempting to stage the play in classical Arabic in the West Bank. The novel’s protagonist, Sonia, an actress living in England, returns to Palestine after eleven years, at a time of emotional and professional drift. She visits her elder sister, who ‘lives in 1948,’ but struggles to communicate with her because of their respective decisions regarding Palestine. It is when she meets Mariam, a theatre director and close friend of her sister’s, that she finds herself cast as Gertrude, Hamlet’s mother.

Why Hamlet?

In her works, Hammad draws a parallel between her subject matter and textual labour. While The Parisian employs a cohesive, traditional structure well-suited to examining the period of nation-state formation – but in contrast to the fragmented narratives found in Palestinian texts – her second novel experiments with form, transforming parts of the narrative into a theatrical play. As Sonia’s ‘outsiderness’ diminishes, text and theatre intertwine further. And as Mehmet Fatih Uslu points out, ‘The novel does not provide an answer or a study of what Hamlet says or has said to Palestinians. Rather, what we read is the reception and experience of a group of Palestinian artists and intellectuals, including Sonia, who are connected to the West.’7

Perhaps thanks to this, in the disconcerted dialogues of the mostly amateur actors, the novel weaves in contemporary realities such as Israel’s control over theatres through funding, the loss of independence due to NGOification, and settlers attending performances armed with weapons. At the same time, it references the history of Palestinian theatre, like the play Darkness mentioned earlier in this article, and incorporates details that root the reader in the region’s past, such as the fact that Hamlet was first staged in the Arab world in Gaza or an Arabic translation that alters the text to give Hamlet a happy ending. Thus, the play becomes a tool through which Hammad guides us back to the past she constructed in her previous novel by following the tracks of her great-grandfather.

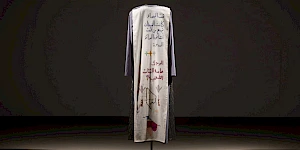

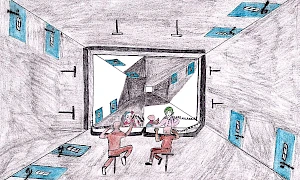

Nadia Michael at the theatre of Friends School during a theatrical performance where she played the role of Hamlet (1960–61). Courtesy The Nadia Mikhail Abboushi Collection, Palestinian Museum Digital Archive, palarchive.org

One might argue that how Shakespeare’s centuries-old texts are treated across geographies has transformed them into a kind of mirror and that Hammad has chosen this ‘mirror’ as a useful platform that may attract the interest of Western readers. However, what allows Hamlet to circulate across different time periods and geographical contexts is also tied to the colonialism at the centre of the Palestinian issue. When asked why she chose Shakespeare, and specifically Hamlet, for a performance on occupied land, Hammad points to the diverse traditions and interpretations, noting its place in the Soviet tradition and post-colonial readings. She adds that during the First Intifada, Hamlet was banned in prisons because certain lines were seen as incitement to violence, and that the phrase ‘to be or not to be’ was translated as ‘shall we be or not be’ in an Arabic version used in Egypt, which became a slogan for Arab nationalism: ‘In fact, the play that in the West is seen as like the psychological drama is also about a historical coming to consciousness of the Arab nation. It has this other history to it and I thought that it was adding to the palette of things I could play around with.’8

The appearance of the ghost of Hamlet’s father and his revelation of the murderer’s identity, the play’s conclusion under occupation and its transformation into a tragedy with almost everyone dying, and Hamlet’s journey of self-discovery collectively present Hammad with the fundamental dynamics that facilitated the play’s ‘other history.’ In the novel, as the actors discuss the plot, the various translations, the characters, and the underlying themes, what weaves the everyday is shaped by where they travel from, the checkpoints they need to pass through to get to the rehearsals, the interrogations they endure, the constant uncertainty over whether the play will be staged, and the performative presence of Israeli soldiers. To use David Naimon’s words, ‘political theatre and the theatricality of politics speak to each other.’9 Within this interplay, it becomes impossible to fix what it means to be Palestinian, and Hammad’s response to the question ‘Where is the inside?’ compounds the pressure.

In the novel, the outermost circle of what it means to be Palestinian in the diaspora is gradually delineated by how often one returns to Palestine or which language one speaks in public. The ripples move inward, and the tension intensifies, depending on where you live in Palestine, whether you were alive in 1948, which side you sold your house to in 1948, whether you are in the West Bank or in Gaza, whether you have gone on hunger strike or died in Palestine. Meanwhile, Sonia’s ‘sense of reality that grows with geographical proximity’ is complicated by her father’s words, who never returned: ‘I came to understand Palestine only after I left it.’

The diversity Hammad has created with her characters is extended to ghosts as well, echoing the novel’s central focus on Hamlet. The ghosts – figures from past generations, martyrs and the displaced – gather into a vast crowd, and we see Palestinians who wish to become ghosts while alive, in order to haunt the occupiers. Becoming a ghost emerges as a fantasy in the face of relentless violation.

In an article written after film-maker Jonathan Glazer’s Oscars speech for The Zone of Interest, Naomi Klein posed a critical question as the massacre in Gaza entered its sixth month: ‘Atrocity is once again becoming ambient. … What do we do to interrupt the momentum of trivialization and normalization? That is the question so many of us are struggling with right now.’10

It was during those days that I turned to literature for answers, which introduced me to Isabella Hammad. As I drew closer to Palestine first through Enter Ghost, and then The Parisian, the momentum Klein speaks of may have appeared to slow, but it did not come to a halt. And the boundaries of literature continue to compel Hammad, as well as many other Palestinian writers, to invent new paths in writing against unrelenting violence.

This text was originally published in Turkish in K24 as part of the ‘Palestinian Literature and Resistance’ series and has been translated into English by Nazım Hikmet Richard Dikbaş. Image selection for L'Internationale Online by Tove Posselt and Ezgi Yurteri.

Related activities

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

HDK-Valand

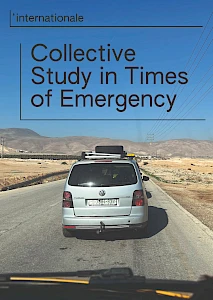

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

Moderna galerija

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

WIELS

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

WIELS

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels. Rana Issa and Shayma Nader

Join us at WIELS for an evening of fiction and poetry as part of L'Internationale Online's 'Collective Study in Times of Emergency' publishing series and public programmes. The series was launched in November 2023 in the wake of the onset of the genocide in Palestine and as a means to process its implications for the cultural sphere beyond the singular statement or utterance.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

–

International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People: Activities

To mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People and in conjunction with our collective text, we, the cultural workers of L'Internationale have compiled a list of programmes, actions and marches taking place accross Europe. Below you will find programmes organized by partner institutions as well as activities initaited by unions and grass roots organisations which we will be joining.

This is a live document and will be updated regularly.

-

–SALT

Screening: A Bunch of Questions with No Answers

This screening is part of a series of programs and actions taking place across L’Internationale partners to mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People.

A Bunch of Questions with No Answers (2025)

Alex Reynolds, Robert Ochshorn

23 hours 10 minutes

English; Turkish subtitles

Related contributions and publications

-

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Rewinding Internationalism

InternationalismsVan Abbemuseum -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale ConfederationEN caInternationalismsStatements and editorials -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay PrashadInternationalismsSonic and Cinema Commons -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

S come Silenzio

Maddalena FragnitoEN itInternationalismsSituated Organizations -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cinq pierres. Une suite de contes

Shayma NaderEN nl frInternationalisms -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Alissar SeylaInternationalisms -

Today, again, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalisms -

Isabella Hammad’ın icatları

Hazal ÖzvarışEN trInternationalisms -

To imagine a century on from the Nakba

Behçet ÇelikEN trInternationalisms -

Internationalisms: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardInternationalisms -

Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

İrem GünaydınInternationalisms -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials -

Poetry Against Language Dioxide

Rana IssaInternationalisms -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations