To imagine a century on from the Nakba

In this review, novelist Behçet Çelik explores Palestine +100 (2019), an anthology featuring twelve short stories that envision a hundred years after the Nakba. Reflecting on themes of memory, absence, forced migration and displacement, the collection illustrates how science fiction can serve as a means to question the present and the past through an imagined future.

Compiled by Basma Ghalayini, Palestine +100 features the short stories of twelve Palestinian writers, aged between 25 and 62 at the time of the book’s publication in 2019, with most in their thirties and forties. Ghalayini invited these writers to imagine the year 2048 – the centenary of the Nakba – resulting in a compelling anthology. It should be clear why I noted the authors’ ages: none of them were alive during the Nakba. These twelve writers – the eldest born nine years and the youngest born forty-nine years after the Nakba – imagined a time approximately a quarter of a century beyond when the stories were written. It is highly probable that they heard stories of the Nakba from their parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents. As Ghalayini emphasizes in her introduction to the book, ‘Four generations on, any Palestinian child can tell you all about their great-grandfather’s back garden in Haifa, Yaffa or Majdal. They can tell you about their great-grandmother’s kitchen, the patterns on her plates, and the colours of the embroidery on her pillows.’1

This child has never been to any of those places, of course, but so long as they keep the memory of them alive, then, should they ever get to go back, it would be as if they had never left; they could pick up exactly where their great-grandparents left off. Indeed, wherever Palestinian refugees are in the world, one thing unites them: their undoubted belief in their right to return.

Palestinian refugees are, in this sense, like nomads travelling across a landscape of memory. They carry their village in their hearts, like an internal compass where ‘north’ is always Palestine. They pass this compass down to their children, who sketch in the details on an ever-fading map—the hills and trees and wadis—from their own imagination.2

It is those children carrying that compass in their hearts who are the writers of Palestine +100, and they travel across the ‘landscape of memory’, to borrow Ghalayini’s phrase. Since memory inevitably evokes the past, one might expect that there should be nothing about memory in stories narrating the future – a century after the Nakba. Yet, ‘When Palestinians write, they write about their past through their present, knowingly or unknowingly,’ states Ghalayini, ‘the past is everything to a Palestinian writer,’ and she adds: ‘It is perhaps for this reason that the genre of science fiction has never been particularly popular among Palestinian authors … . The cruel present (and the traumatic past) have too firm a grip on Palestinian writers’ imaginations for fanciful ventures into possible futures.’3

Ghalayini points to another reason why science fiction is less appealing to Palestinian writers:

In classic SF, the battle lines are drawn quickly and simply: the moral opposition between a typical SF protagonist and the dystopia or enemy he finds himself confronting is a diametric one. But in Palestinian fiction, the idea of an ‘enemy’ is largely absent. Israelis hardly ever feature, as individuals, and when they do, they are rarely portrayed as out-and-out villains.4

It is here that Ghalayini introduces Ghassan Kanafani’s novella Returning to Haifa (1969) as an example. She highlights how the settler woman in the story is portrayed not as a fanatic, but as a sensitive, compassionate individual who feels embarrassed when she confronts what her people have done to the Palestinians:

The absence of an ‘enemy’ isn’t the only absence in Palestinian fiction. You might even say absence generally is one of the defining features of Palestinian fiction—which is where science fiction might be able to contribute. Absence, and the feelings of isolation and detachment that come with it, are easy to magnify in a context of galloping future technology.5

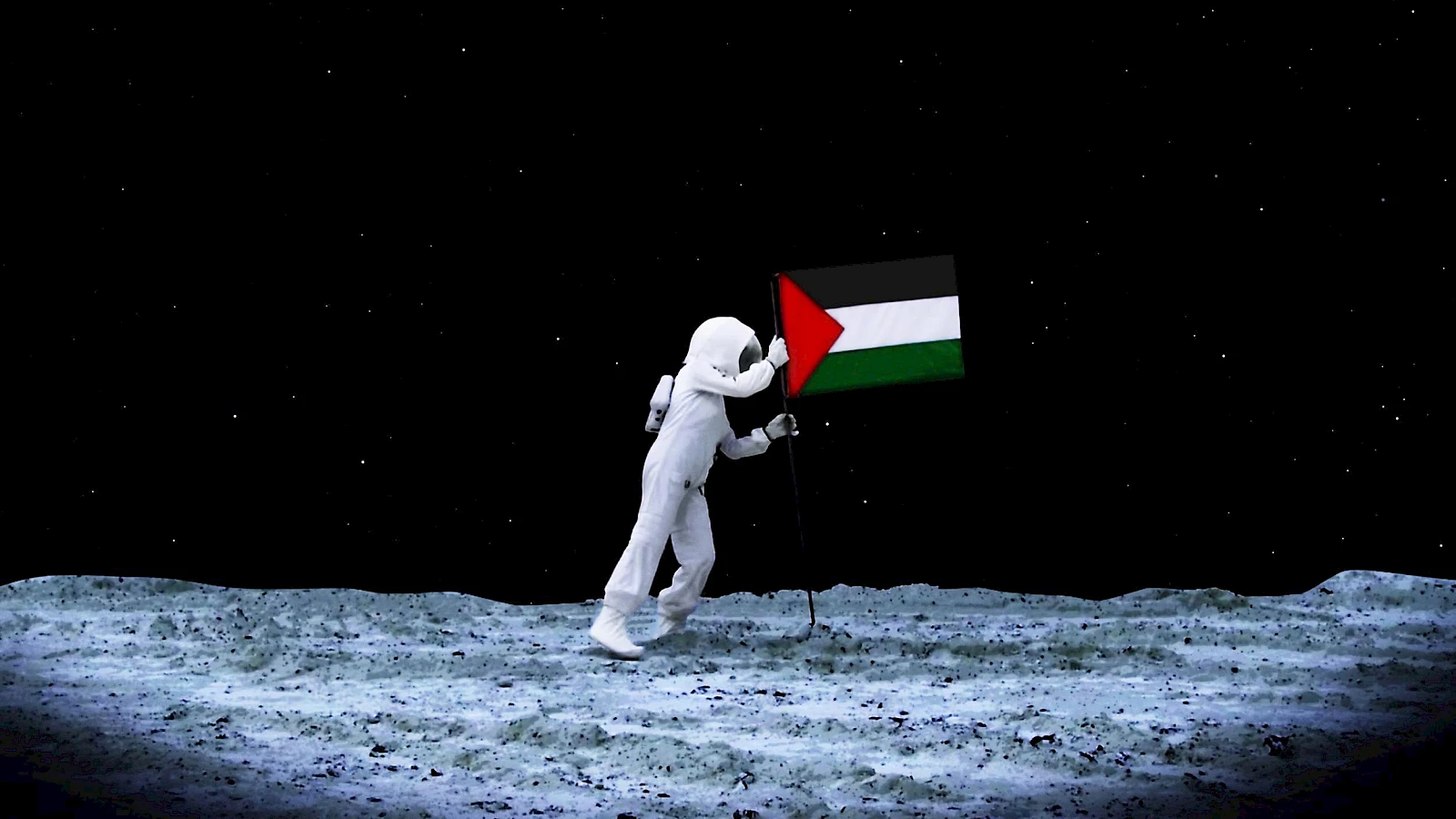

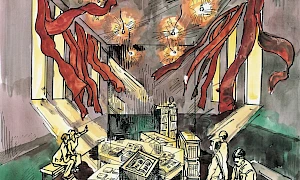

Larissa Sansour, still from A Space Exodus, film, 5’, 2009. Courtesy the artist.

Another distinguishing feature of Palestinian science fiction, according to Ghalayini, is that it focuses on cultural disconnections between refugees from different communities or generations, and science fiction offers intriguing possibilities to explore this issue via alternative realities. As an example, she presents the story ‘N’ by Majd Kayyal, included in the anthology, in which he invents a cosmological solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict. In the story, there are two parallel worlds occupying the same geographical area, and only those Palestinians born after the creation of these worlds are allowed to travel between them. The child protagonist uses this right and travels to the Israeli world to study. As Ghalayini claims, this extraordinary vision of the future, pointing towards the cultural rupture between father and son, reflects and reframes the generational clash in reality:

But that’s what science fiction does; it uses the future as a blank canvas on which to project concerns that occupy society right now. The real future—the actual future—is unknowable. But for SF writers, the mere idea of ‘things to come’ is licence to re-imagine, re-configure, and re-interrogate the present.6

Ghalayini argues that the allegorical reframing of the present (whether as an imagined future or not) is becoming increasingly significant, given, on the one hand, the stance of repressive regimes like Sisi’s in Egypt, and on the other hand, the immediate accusations of antisemitism in the West against writers who address the Palestinian issue. Finally, she draws attention to the fact that the current everyday life of Palestinians is very much a kind of dystopia:

A West Bank Palestinian need only record their journey to work, or talk back to an IDF soldier at a checkpoint, or forget to carry their ID card, or simply look out their car window at the walls, weaponry and barbed wire plastering the landscape, to know what a modern, totalitarian occupation is—something people in the West can only begin to understand through the language of dystopia.7

Certain common themes emerge in the short stories included in Palestine +100. For instance, it is striking how virtual reality comes to the fore in the stories’ imagined futures. This would likely be the case in any anthology commissioning future-set stories – whether they be about Palestine or not. There is something about virtual reality that both writers and scriptwriters find compelling – partly because we are already experiencing it. Likewise, the stories in the book, as Ghalayini emphasizes, often focus on the issue of memory, which is also treated as a kind of ‘virtual’ reality. In Saleem Haddad’s ‘Song of the Birds’, a young girl named Aya, after the suicide of her brother, is ‘saddled by the weight of things,’ and more strikingly, feels ‘trapped in someone else’s memory.’ At first, the story leaves this unexplained, but later, when Aya dreams of her brother Ziad and speaks to him, he clarifies her feelings, especially with the following lines: ‘You know how us Arabs are. We are trapped in the rose-tinted memories of our ancestors. … We’re just another generation imprisoned by our parents’ nostalgia.’8

As Aya talks with her brother in her dream, the ‘tranquil’ reality she has known is suddenly torn away, and she begins to witness scenes from another world – one marked by destruction, where even the sea is no longer blue but brown – and she grasps the essence of the matter. This condition is reflected in Ziad’s journal, which Aya finds at home:

There is an oral tradition of grandparents passing on their stories of Palestine, which helps keep Palestine alive. But is it not too much of a stretch for them to have figured out how to use these stories to imprison us? The truth of collective memories is that you can’t just choose to harness the good ones. Sooner or later, the ugly ones begin to seep in too…9

Aya and her family live in a simulation based on ‘parents’ nostalgia.’ Those who were alive before this simulation was created, the parents, sleep for most of the day. They are aware of the structural difference between the past and the present, but unlike Ziad, they cannot choose death to leave the simulation, because they don’t want to abandon their children, those born after the creation of the simulation. This particularly reflects Aya’s mother, who almost always retreats into sleep. Aya is largely convinced by Ziad’s account, yet finds herself confused the moment she tries to imagine the simulation: ‘Her brain tried to imagine it, but it was like trying to visualise what happens after the world ends, or else trying to imagine the full force of the sun. … It was unfathomable, the experience too all-encompassing.’10

It is her brother who enables Aya to navigate between the two worlds – dreams and waking consciousness – but once she stops seeing Ziad in her dreams, she loses that ability. Yet, ‘there was no way she could keep living like this, not knowing what was true and what was false, what was reality and what was merely an enforced dreamland.’11 She has no choice but to try to experience it. The only clue she has is a detail Ziad pointed out: the birds always have the same chirping sound in the simulation. This short story can be understood as science fiction questioning the present and the past through an imagined future. It serves as an allegory for the dead-end Palestinians face when, instead of focusing on the demands of the new times and the changes that have occurred, and seeking new paths, they aim for the tranquil times supposedly lived once upon a time. Of course, as a literary work, the story does not offer or dictate solutions; it merely cautions against assuming that the path followed until now is the only one, and against falling for the illusion (or ‘dream’) that the world we inhabit is absolute and without alternatives.

Larissa Sansour, still from A Space Exodus, film, 5’, 2009. Courtesy the artist.

In Saleem Haddad’s story, simulation or virtual reality functions as a trap, a state of incarceration; yet in other stories, it becomes a means of emancipation. One example is Emad El-Din Aysha’s ‘Digital Nation’. Told from the viewpoint of a Shabak (Israeli Security Agency) director, the story presents the vision of a United Palestinian State simulated in great detail. A virus containing this simulation has infected the virtual reality consoles used by all Israelis, from cyber kids on roller skates to solitary housewives waiting for their Amazon deliveries. The next move comes when every screen in Israel (in schools or on the stock market) is replaced by text in the Arab script. From there, the story unfolds:

If it wasn’t for the old-fashioned physical street signs, people wouldn’t have known what country they were living in. Virtual tour guides, eBooks and online atlases all began rewriting themselves, telling tourists they were, in fact, in Palestine, and replacing all Hebrew names with their pre-1948 Arabic ones. Even printing machines were hacked, meaning all map books came out in Arabic, branded with a Palestinian flag, still upside down in preparation for liberation day.

Soon the geostationary satellites floating up above Israel were infected, and all digital signals coming into the country came in Arabic. Record companies began going broke. The music channels started shutting down. Stereo systems, mp3 players, smartphones, all began turning themselves on, and blaring out hit singles from 1948, mixed in with contemporary Arabic grime, rap and R&B.12

As the virus spreads, youngsters in different parts of the world also come into the picture:

Although technically Palestinians, the two boys had grown up in a variety of different countries, only really calling the virtual landscape of gaming ‘home’. It didn’t matter to them where, geographically speaking, any new craze or meme originated from. If it was trending, they wanted in.

And this was trending: an announcement from cyberspace, made simultaneously to every chatroom on the globe, declaring the formation of the world’s first virtual government. It was a council of long-dead historical figures, apparently, that most gamers would never have heard of—Abu Ammar, Hannan Ashrawi, Ezz Il Din Al-Qasam, Abu Ali Mustafa, Mousa Al-Sadr and so on. Each had their own ministerial portfolios and the player’s task was to pick one, and with them form a cabinet to address pressing economic and international challenges. What distinguished this from an elaborate version of The Sims, however, was the fact that real-world problems and requests were being fed into the game.13

Then, in Ahmed Masoud’s story ‘Application 39’, we are introduced to two hackers. When we meet them, the connections between Palestinian cities have been severed both by land and air. However, a network of underground tunnels, with functioning elevators, connects the cities (each now a city-state). Rayyan and Ismael have not been able to return to their families since the war that began in 2025. It was right after this period that Palestinian cities, unable to maintain physical contact, declared themselves independent states.

‘Air travel had not been possible since the end of the twentieth century, so the city-states had put everything into tunnelling back into contact with each other – starting with shabby old holes Hamas had first dug during its rule.’14 Notably, the story’s narrator refers to the period before the 2025 War as ‘the rule of Hamas and Fateh,’ which could be considered as an example of presenting a picture of the present while narrating the future.

I have mentioned that Rayyan and Ismael are hackers, but they don’t hack the systems of the enemy nation. Rather, they apply to host the 2048 Olympic Games in Gaza by forging the signature of their own head of state. Once this forgery is revealed, a top-level female administrator, Lamma, takes them to the president of the State of Gaza, but to her surprise, the president finds the idea of hosting the Olympics quite plausible, believing it could be an opportunity to unite all Palestinian city-states. Afterward, Lamma asks how they intend to make it happen: ‘How are we going to host a marathon, for instance, when the city’s only six kilometres wide? Or the water sports—rowing, sailing, long-distance swimming—when we only have a two-mile long stretch of coast?’15

The answer, as one may presume, is to ‘build tunnels.’ Swimming lanes can be set up along the two-mile coast, and the seabed excavated for diving. Needless to say, this project is far from straightforward. In his short story, Masoud points not only to Israel as the source of the problem, but also to another city-state, suggesting that one of the fundamental issues of Palestine is dividedness.

The book also features a virtual wall story. While Majd Kayyal’s aforementioned story ‘N’ depicted two parallel worlds existing on the same land, Anwar Hamed’s ‘The Key’ introduces a ‘gravity wall’ – ‘a transparent shield, created by a subatomic “tampering” with the gravitational field along certain geographic coordinates.’ And ‘only those with the right chip (implanted in the neck of all newborns), and chips with the right code’ may pass through the gates in the wall, where the gravitational distortion is perforated.16

There are two reasons for the construction of such a wall. The first is that the idea of returning home is still very much alive for Palestinians who have been displaced from their homes and for their descendants. Thus, the Israeli narrator explains that his grandfather, who worked at the institution responsible for the construction of the wall, feared, more than weapons, the keys Palestinians still kept to the homes they had once lived in. Those who shared his grandfather’s view chose to build this ‘gravity wall,’ having observed that physical walls were of no use at all. Psychologically, the concrete walls had the exact opposite effect. However, this transparent wall would not work either, since, even though the wall was no longer tangible, the locks on the doors of the homes remained as real as ever.

In future-set stories, the arrival of aliens on Earth is hardly surprising – and so it is in Talal Abu Shawish’s story ‘Final Warning’. Set in Ramallah and Modi’in Illit, a city of Jewish settlers, the story begins when, one morning, the people wake up to a world where time has stopped, and all electronic devices have failed. Muslims, Jews, and Christians alike are gripped by panic, believing judgment day has arrived, and each community gathers around its religious cleric. They soon realize the presence of a massive spaceship, from which a voice declares that the destruction of this part of the world would be instantaneous and that they have come for a final warning:

Your struggles in this tiny sector of the planet’s surface have, for more than a hundred of your planet’s orbits, caused more tension and conflict, directly and indirectly, beyond its borders than any other area of its size in the known universe. Your conflict acts as a symbol, a case study, a metaphor, a lightning rod, a red rag for conflicts across the entire planet’s surface. By continuing to threaten the planet’s stability as a whole, you also threaten the wider galaxy’s stability…17

The people take this warning seriously and disperse, deep in thought, after the spaceship departs. However, at the end of the story, settlers heading towards Modi’in Illit discover that a new wall has been built – the only solution politicians and administrators seem to know.

A key point where the visions of the future in two short stories from Palestine +100 converge is the development of artificial, robotic limbs. Considering tens of thousands have been left disabled in the ongoing wars and clashes since the Nakba, in addition to those who lost their lives, it is no surprise that Palestinian authors touch upon this matter as they imagine the future. Another striking commonality in the stories, alongside technology, is the discovery of new means and methods for control and surveillance. We often come across this in works of dystopian science fiction. It has been a recurring motif since the early days of the genre that technology brings captivity rather than emancipation and increases the sovereign’s power of control and surveillance. Strikingly, the situation in ‘real life’ is no different than ‘fiction’. In this specific context, it is another reality that, alongside the massacre and genocide of Palestinians by Israelis in wartime, advanced control and surveillance mechanisms are also in force during so-called peacetime. Another detail that drew my attention is from Tasnim Abutakbih’s ‘Revenge’. It mentions that during the founding years of Israel, some Palestinians sold land to Israel, though these transactions were mostly involuntary. Once again, we witness how, in envisioning the future, the authors do not refrain from reassessing the past.

Finally, I would like to touch upon the longest and most humorous story in the collection: ‘The Curse of the Mud Ball Kid’ by Mazen Maarouf. The forced seizure of the homes of Palestinians, their forced migration, and the presence of the wall are interwoven in this story. The narrator once lived with his grandmother and sister in a house at the far end of the village, just a few meters from the wall separating the village of the Palestinians from the kibbutz of the settlers. Behind the wall, there is a guava tree that once belonged to his grandmother. Of course, not just the tree, but the land it grows on used to be hers, but now, a kibbutznik named Amir lives there and tends to it. This situation is reminiscent of the past – the before-and-after of the Nakba – so what does it look like a century later? The opening lines of the story offer a glimpse: ‘I’ve always wanted to be a superhero. I didn’t want to save the world, or even save all the children of Falasta. I just wanted to save my sister when they came to steal her imagination. If you had asked me then what kind of superhero I wanted to be, I would have said an extremely small creature, one that tracks down germs and bacteria in the bodies of children and destroys it.’18

The country has been divided into two, Falasta and Greater Israel, and yet again, a wall has been erected between them. On top of the wall, detectors have been installed that would electrocute to death even a mosquito attempting to cross into Greater Israel. In the sky, there is an artificial satellite called Dabraya Star, emitting a gravity wind composed of graviton particles (recalling the ‘gravity wall’ in Anwar Hamed’s story ‘The Key’). Every night, the wind blows and extracts from the children of Falasta all they have imagined during the day. These imaginations are then drawn up to Dabraya, stored there, and inserted into the minds of the children of Greater Israel when they need it. However, the narrator explains that the Jewish children whose imaginations have been damaged do not benefit from the beaming of the imaginations of southern Falasta’s children: ‘this only made them feel like they were trapped in the imagination of some other, unfamiliar kid, which would make them freak out.’19 (In this context of being trapped in someone else’s imagination, we can also recall Saleem Haddad’s story ‘Song of the Birds’, where Ziad talks about being imprisoned by the nostalgia and memories of his ancestors.)

Meanwhile, the graviton wind of the Dabraya Star has failed to steal the narrator’s imagination. He has thought so deeply about the robomicrobe – a tiny creature that follows microbes – and has fixed this vision so firmly in his mind that the wind has failed to steal his imagination from him. Imagining the robomicrobe so frequently has given him immunity.

Maarouf continues this long story with an abundance of metaphors, without recounting them all, I can add this: at one point, the narrator stuffs his mouth with mud to protect himself from machine-gun bullets, transforming into a mud ball, and thus becoming the last Falasti survivor. The Israelis know that this last Falasti stores the energy of all his people, so they put him in a glass cube, fearing the power that might be unleashed in the event of his death. After Falasta ceases to exist, the kibbutzes expand even further, and more significantly, begin to have disputes among themselves over land, borders, river water, fruit, and other primary resources. Meanwhile, the kibbutz residents start seeing Falasti ghosts, first in their gardens, then all around. Ghosts, in fact, appear to be the most recurring motif in Palestine +100. But in this story, Maarouf looks at the ghost metaphor from a completely different angle. ‘In fact, the kibbutzniks might as well be the ones who are ghosts.’ The question posed by the narrator’s Jewish friend Ze’ev to a group of Jewish children captures this possibility:

Can any of you prove that they are the ghosts and not us?20

This text was originally published in Turkish in K24 as part of the ‘Palestinian Literature and Resistance’ series and has been translated into English by Nazım Hikmet Richard Dikbaş.

Related activities

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

HDK-Valand

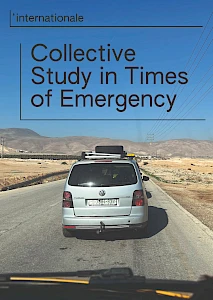

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

Moderna galerija

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

WIELS

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

WIELS

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels. Rana Issa and Shayma Nader

Join us at WIELS for an evening of fiction and poetry as part of L'Internationale Online's 'Collective Study in Times of Emergency' publishing series and public programmes. The series was launched in November 2023 in the wake of the onset of the genocide in Palestine and as a means to process its implications for the cultural sphere beyond the singular statement or utterance.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

–

International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People: Activities

To mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People and in conjunction with our collective text, we, the cultural workers of L'Internationale have compiled a list of programmes, actions and marches taking place accross Europe. Below you will find programmes organized by partner institutions as well as activities initaited by unions and grass roots organisations which we will be joining.

This is a live document and will be updated regularly.

-

–SALT

Screening: A Bunch of Questions with No Answers

This screening is part of a series of programs and actions taking place across L’Internationale partners to mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People.

A Bunch of Questions with No Answers (2025)

Alex Reynolds, Robert Ochshorn

23 hours 10 minutes

English; Turkish subtitles

Related contributions and publications

-

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Rewinding Internationalism

InternationalismsVan Abbemuseum -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale ConfederationEN caInternationalismsStatements and editorials -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay PrashadInternationalismsSonic and Cinema Commons -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

S come Silenzio

Maddalena FragnitoEN itInternationalismsSituated Organizations -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cinq pierres. Une suite de contes

Shayma NaderEN nl frInternationalisms -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Alissar SeylaInternationalisms -

Today, again, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalisms -

Isabella Hammad’ın icatları

Hazal ÖzvarışEN trInternationalisms -

To imagine a century on from the Nakba

Behçet ÇelikEN trInternationalisms -

Internationalisms: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardInternationalisms -

Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

İrem GünaydınInternationalisms -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials -

Poetry Against Language Dioxide

Rana IssaInternationalisms -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations