I don’t wish to die trapped under the rubble of my home

until my corpse rots amid the wreckage

I don’t wish to die in pieces scattered here and there

so my casket isn’t a black plastic bag

I don’t wish to die on the sidewalk by a sniper

where stray dogs feast on my remains

I don’t want to die and for my body to burn

leaving my mom and dad unable to recognize me

– Poem written on the rubble of a home in Gaza by an anonymous poet

Blessed is the blood of our martyrs. Blessed is our poisoned earth. Avenge us beloved Mother avenge the blood of our children & the tortured bodies of our people. Send your seas and drown the barbarians & protect our people in Palestine.

– A prayer I wrote

From the earliest days of their dispossession, Palestinians have recorded their plight in poetry.1.I am profoundly grateful for the valuable feedback of my dear friends Jumana Manna and Wendy Lotterman. An earlier, much shorter version of this piece was published on L’Internationale Online on 4 March 2024, internationaleonline.org, then included in the Collective Study in Times of Emergency e-book, December 2024, internationaleonline.org/publications. This longer version was solicited by De Appel, Amsterdam, on 11 May 2025. A more polished version was presented at WIELS, Forest, Belgium, on 24 June 2025. The feedback I received on those later iterations was crucial for this final version of the piece. I am grateful to my editor, Nick Aikens, for working so closely with me to develop the piece throughout this period. There is a long tradition of this among Arabs who, since long before the birth of Islam, have considered poetry a diwan, a historical record. Palestinian poets are also Arab poets; they find inspiration in a poetic tradition that is geographically expansive and predates the Zionist project by more than a millennium. Unlike historical writing, for which Arabs are also renowned, poetry is a mnemonic device that penetrates people’s consciousness and registers, and shapes their affective state. While historical writing on Palestine can document pain and loss, Palestinian poetry actively resists what the martyred political prisoner Walid Daqqa terms ‘language dioxide’, or the ‘garbage of language’ – the language of oppression.2.Abdel Rahim al-Sheikh, ‘Al-makan al-muwazi: rasm al-zaman fi fikr Walid Daqqa’, Mussassat al-dirasat al-filastiniya, Beirut: Sayf, 2023, pp. 187–22, 187. Poetry refuses the banalization of language and testifies against injustice, enshrining the form as both diwan and protest. Palestinians learn and memorize poetry as well as produce it. Through poetry, they cultivate their political imagination and preserve their collective spirit.

Pull Yourself Together

Heba Abu Nada

trans. Huda Fakhreddine

Pull Yourself Together

Heba Abu Nada

trans. Huda Fakhreddine

O! How alone we are!

All the others have won their wars

and you were left in your mud,

barren.

Darwish, don’t you know?

No poetry will return to the lonely

what was lost, what was

stolen.

How alone we are!

This is another age of ignorance. Cursed are those

who divided us in war and marched in your funeral

as one.

How alone we are!

This earth is an open market,

and your great countries have been auctioned away,

gone!

How alone we are!

This is an age of insolence,

and no one will stand by our side,

Never.

O! How alone we are!

Wipe away your poems, old and new,

and all these tears. And you, O Palestine,

pull yourself together.

The poetic becomes an occasion to restore language to meaning, and vice versa to express the trials of Palestinians as they face the necropolitics of the settler regime. In Arabic, there are semantic connections that bind words: meaning, maana; prohibition, man’; suffering, muaanat; and care, inaya. These four words share a three-letter root, which, for lexicographers, indicates a semantic logic that maintains the bond between prohibition and the necessity of meaning-making in trying times as a form of care and repair that alleviates suffering. Since the beginning of this genocide, I have been battling with maana and its family of words in my personal quest to work through the grief of witnessing the extermination of my people and the prohibition that world powers have enforced on Palestinian mourning. I learned during this time the paradox of grief. Through my grief, I sensed a function of poetry for Palestinians today. On one hand, grief can drive us to isolation, an unsurmountable loneliness; on the other hand, through ritual performances of grief – through demonstrations and funerals, as well as other communal acts like writing, organizing, witnessing – we search to overcome our psychic isolation to connect with others. Like Refaat al-Areer’s poem, ‘If I Must Die’,3.Refaat al-Areer, ‘If I Must Die’, posted by the poet to x.com in English on 1 November 2023 with the post, ‘If I must die, let it be a tale #FreePalestine #Gaza’, x.com. which circulated widely after his murder alongside most of his family in Gaza on 6 December 2023 – his death is meaningful so long as there are those who live to tell and share the story. This is the grief that permeates the poetry of Heba Abu Nada, who was martyred in Gaza on 20 October 2023. In ‘Pull Yourself Together’, Abu Nada demands that she and her people remain steadfast in the face of grief; ‘How alone we are!’ becomes the refrain that carries the people through their helplessness vis-à-vis the world in the ‘age of insolence’. Poetry, she writes, cannot return ‘to the lonely / what was lost, what was / stolen’. Poetry is akin to tears to be wept then wiped away, and Palestinians, the poet cries out, must pull themselves together.

Palestinian poetry, whether written in Palestine, in exile, in Arabic, in other languages, by Palestinians, or by poets in solidarity, is framed by land struggle. The figure of the poet in this struggle can be understood through the negation of lived space, through dispossession. In the camp and in the prison cell, the Palestinian refugee and prisoner are forced into the architectural markers of Zionism, spaces of unsettledness, incarceration and colonial deadliness. The camp and the prison cell are spatial forms that theorist Nasser Abourahme describes as consisting of ‘a flexible mixture of penal-carceral, extractive, labor exploitative, demographic, and territorial logics’.4.Nasser Abourahme, The Time Beneath the Concrete: Palestine Between Camp and Colony, Durham: Duke University Press, 2025, p. 5.

Palestinian subjects of incarceration and displacement grapple with erasure and deracination and long for liberated forms of belonging to Palestine, as well as to the foreign environments they inhabit as refugees. Palestinian writing challenges how literature continues to be traditionally catalogued and studied. Firstly, it exceeds the conceptualization of literature within nationalist frameworks – whether written in Arabic, or in the other languages poets have used to articulate their Palestinian identities. As scholar Refqa Abu Remaileh writes, ‘refugees’ complex ties to various and multiple geographies can distort, problematize, and perforate conceptions of national literatures.’5.Refqa Abu Remaileh, ‘Country of Words: Palestinian Literature in the Digital Age of the Refugee’, Journal of Arabic Literature, vol. 52, 2021, p. 70. The figure of the refugee foregrounds the Palestinian subject because the persistent Israeli annexation of Palestinian lands places any Palestinian who survives Israeli violence under the threat of becoming a refugee.

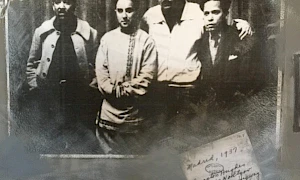

Secondly, incarceration encloses the compass of Palestinian poetry, in the sense that the threat and realities of the imprisonment of Palestinians produce a schizophrenic kind of relation to time and space. Kaleem Hawa writes that the split between self and body produces a ‘process of derealization, what Daqqa defined as, “the state of losing the ability to interpret reality”.’6.Kaleem Hawa, ‘Like a Bag Trying to Empty: On the Palestinian Prisoner and Martyr Walid Daqqa’, Parapraxis, 24 August 2024, parapraxismagazine.com. Poetry must reckon with this derealization in its contemplation of the body within time-space coordinates. In the complexities of belonging that confront Palestinian poets, their poetry expresses the difficulties of inhabiting the spaces forced upon them. The prisoner redraws the minimality of incarcerated space and struggles to connect the small prison they are within to the big prison that is Palestine. Political prisoners challenge their atomization and the idea of their defeat through these acts of symbolic collective return. These returns restore connections and open new possibilities for solidarity and the entwining of fates. This is how Black Panther Party leading member George Jackson reties the Palestinians to their Black comrades: mistakenly, and poignantly, taken to be the writer of ‘Enemy of the Sun’ by Samih al-Qasim, when the poem was published, following Jackson’s assassination by prison guards, in a Black Panther Party paper. Jackson had previously copied out the poem by hand.7.The poem appeared as a full-page spread in The Black Panther Intercommunal News Service, 25 September 1971. See Derek Ford, ‘A common enemy of the sun: George Jackson and Samih al-Qasim’, Indy Liberation Center, 15 February 2024, indyliberationcenter.org. The mistake fixed the bond between the Palestinian and Black radical movements, and reveals the extent to which our predicaments are intertwined.8.For more on the history of this poem, listen to Greg Thomas speak to Shireen Hamza (host), ‘George Jackson in the Sun of Palestine’, Ottoman History Podcast, ep. 366, 11 July 2018, ottomanhistorypodcast.com.

Enemy of the Sun

Samih al-Qasim

(read and loved by George Jackson)

Enemy of the Sun

Samih al-Qasim

(read and loved by George Jackson)

I may – if you wish – lose my livelihood

I may sell my shirt and bed.

I may work as a stone cutter,

A street sweeper, a porter.

I may clean your stores

Or rummage your garbage for food.

I may lie down hungry,

O enemy of the sun,

But

I shall not compromise

And to the last pulse in my veins

I shall resist.

You may take the last strip of my land,

Feed my youth to prison cells.

You may plunder my heritage.

You may burn my books, my poems

Or feed my flesh to the dogs.

You may spread a web of terror

On the roofs of my village,

O enemy of the sun,

But

I shall not compromise

And to the last pulse in my veins

I shall resist.

You may put out the light in my eyes.

You may deprive me of my mother’s kisses.

You may curse my father, my people.

You may distort my history,

You may deprive my children of a smile

And of life’s necessities.

You may fool my friends with a borrowed face.

You may build walls of hatred around me.

You may glue my eyes to humiliations,

O enemy of the sun,

But

I shall not compromise

And to the last pulse in my veins

I shall resist.

O enemy of the sun

The decorations are raised at the port.

The ejaculations fill the air,

A glow in the hearts,

And in the horizon

A sail is seen

Challenging the wind

And the depths.

It is Ulysses

Returning home

From the sea of loss

It is the return of the sun,

Of my exiled ones

And for her sake, and his

I swear

I shall not compromise

And to the last pulse in my veins

I shall resist,

Resist – and resist.

This resilience does nothing to halt the velocity of displacement facing Palestinians. The lost land is not only a thing of the past but also a loss that structures the relation to the present and opens up questions about what possibilities lie in the future.

Phobia

Najwan Darwish

trans. Kareem James Abu Zeid

Phobia

Najwan Darwish

trans. Kareem James Abu Zeid

I’ll be banished from the city

Before night falls: They’ll claim

I neglected to pay for the air

I’ll be banished from the city

Before the advent of evening: They’ll claim

I paid no rent for the sun

Nor any fees for the clouds

I’ll be banished from the city

Before the sun rises: They’ll say

I gave night grief

And failed to lift my praises to the stars

I’ll be banished from the city

Before I’ve even left the womb

Because all I did for seven months

Was write poems and wait to be

I’ll be banished from being

Because I’m partial to the void

I’ll be banished from the void

For my suspect ties to being

I’ll be banished from both being and the void

Because I was born of becoming

I’ll be banished

‘Phobia’ lists the impossible monetization of life, which is the cardinal method that leads to banishment. The ongoing loss of land is the backdrop for lived experiences of dispossession under oppression and leaves its mark on every Palestinian regardless of the type of brutalization they or their loved ones have undergone. In ‘A Litany for “One Land”, After Audre Lorde’, Mosab Abu Toha, from Gaza, addresses Israeli citizens, and cannot fathom how they can watch and be complicit with the genocidal violence of the Zionist entity.

A Litany for 'One Land’

After Audre Lorde

Mosab Abu Toha

A Litany for 'One Land’

After Audre Lorde

Mosab Abu Toha

For those living on the other side,

we can see you, we can see the rain

when it pours on your (our) fields, on your (our) valleys,

and when it slides down the roofs of your ‘modern’ houses

(built atop our homes).

Can you take off your sunglasses and look at us here,

see how the rain has flooded our streets,

how the children’s umbrellas have been pierced

by a prickly downpour on their way to school?

The trees you see have been watered with our tears.

They bear no fruit.

The red roses take their color from our blood.

They smell of death.

The river that separates us from you is just

a mirage you created when you expelled us.

IT IS ONE LAND!

For those who are standing on the other side

shooting at us, spitting on us,

how long can you stand there, fenced by hate?

Are you going to keep your black glasses on until

you’re unable to put them down?

Soon we won’t be here for you to watch.

It won’t matter if you blink your eyes or not,

if you can stand or not.

You won’t cross that river

to take more lands,

because you will vanish into your mirage.

You can’t build a new colony on our graves.

And when we die,

our bones will continue to grow,

to reach and intertwine with the roots of the olive

and orange trees, to bathe in the sweet Yaffa sea.

One day, we will be born again when you’re not there.

Because this lands knows us. She is our mother.

When we die, we’re just resting in her womb

until the darkness is cleared.

For those who are NOT here anymore,

We have been here forever.

We have been speaking but you

never cared to listen.

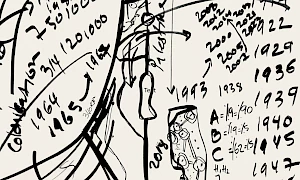

In facing spatial dispossession, time becomes the organizing axis for imagining Palestine. Time, for Palestinians, is a measure for lives facing colonial oppression, for individuals, as well as fractured collectives, and does not lend itself to a cohesive national narrative. For a Palestinian prisoner, time moves differently than time spent in a refugee camp, in exile, or in genocide. The temporalities that make up Palestinian social and political identification capture the heterogeneity of Palestinian experiences and have been a running theme in Palestinian poetry since 1948. Time is measured in the number of martyrs, as Gazan Nasser Rabah says in his poem ‘In the Endless War’.

In the Endless War

Nasser Rabah

trans. The Brooklyn Translation Collective

In the Endless War

Nasser Rabah

trans. The Brooklyn Translation Collective

Put your hearts under the beds—exhausted neglected shoes

not to be covered by the dust of war:

‘and you shall not know’.

Put your hearts on the case of an old and broken clock,

so the raid won’t shake them:

‘and you shall not be sad’.

In war the heart expands, becoming a boat for the children, an hour of

clarity, and a sky for writing.

In war the heart chokes, words flee, and along its edge birds melt into

red dew.

It flutters on a tall post—a gasp called the homeland.

In war you leave your heart aside and you salvage a bundle of paper:

your old picture at the school gate, the deed of your demolished home,

your son’s birth certificate.

Your heart doesn’t matter now. The beloved will await war’s end to

ask: did you remember me?

In war no one believes your grief-stricken heart. The rescuers scale

your arms to hold up the roof of sobbing, the planes land their

shadows around you, and your soul flies out like a flock of glass.

You are the time and nothing aims a piece of shrapnel at a soul but

you. Maybe you long to throw your heart at your children like a ball.

Maybe you long to open the window without the shot of a stray

woman. It’s alright, it’s war, another one and it will pass.

In war time commits suicide.

The day goes by before it’s your turn for the bathroom. The hour is

that space between a building embraced by a missile and another

one opening its chest for the last person gasping on

a street about to exit history instantaneously. As for the minute, no

minutes in war, time is rather measured by martyrs:

a hundred and a thousand. In war we sit, no legs to carry us and run.

In war a missile follows you like a loyal dog and a boring neighbor

exchanging greetings and bad jokes.

You etch a tattoo shaped like home into memory.

It was a beautiful home before the arrival of the missile.

In war the children are embarrassed by their tantrums, they grow

before us as if we’re meeting old neighbors. How are you, son? I’m still

running father, I’m still running, alone in the madness race.

In war you brought me into the experience. You’re the one who

dragged the fairytale’s ghouls to my door. You’re the one who with

premeditation forgot the barbecue on, and I’m screaming: it’s my

heart. You did not hear and you did not forgive. Of love, you left

nothing; of hate, you left nothing for me to finish the poem. Then

you, like a pale cloud of smoke, deceived me into safety.

In war life envies you for life. Gangrene homes, windows of hysteria,

and the eczema of streets, everything in the horrifying scene resents

that you could see it all and not cry.

In war you’re not made of flesh and bones, you’re someone else in the

same clothes, bloodied, dirty, and lying—testifying that you’re not

dead yet.

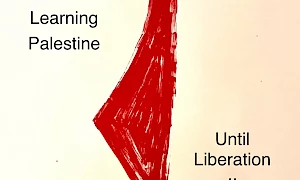

Palestinians also measure their geography in the number of years of nakba, which has dispossessed them since 1948, as diasporic Palestinian Hala Alayan proposes.

When they say pledge allegiance, I say

Hala Alayan

When they say pledge allegiance, I say

Hala Alayan

my country is a ghost // a mouth trying to say sorry and it comes out all smog // all citizen and bullet and seed // my country is a machine // a spell of bad weather // a feather lacing my mother’s black hair // I mean her dyed hair // I mean her blonde hair // I mean her hair matches my country // so shiny and borrowed and painted over // my country is a number

like—

it is 1948 and my great-great-grandmother flattens bread with her hands // while my other great-great-grandmother prays with her hands // one watches her land disappear // the other builds a house on land that will disappear

my country is an airport line a year of highways an intermission // my country is Stockholm syndrome // is immigrant mouth saying thank you saying please saying // my country is no country but ghost // is no man but ghost // my country is dead // my country is name the dead // give them their salt

my country is a mouth trying to say pledge and it comes out all salt // my country is a mouth and nobody can pronounce my name // I mean my country forgets my name // I mean my country is always asking for my name // and I’m always saying it twice // spelling it like an address // my country is a number

like—

it is 1967 and every Arab leader is crying every mother is clutching // the sons she has left and my great-grandmother names my mother // nostalgia while my other great-grandmother names my father // a gun // my country is all ghost // my grandmother is all ghost // my grandmother is a country I mean my grandmother is my country // I mean my country is a lie is an emptied house is one thousand cardboard boxes // my country is remember when we left Akka // I mean Gaza // I mean Homs // my country is a number

like—

it is 1990 // my mother is crossing a border I mean desert I mean life // I am at her heels // I am paying attention // I mean I am learning to pray to a flag // I mean I am learning English // I mean I am forgetting Arabic

or—

it is 1994 and I am falling in love with a white boy // a habit I’ll never kick

or—

it is 2006 and my grandparents won’t evacuate // won’t leave another war // and all summer I dream of floods // collect bullets and love the wrong person

or—

it is 2003 and I am in Beirut watching Baghdad burn because of America // I mean I am in my country // watching my country burn because of my // country

or—

it is 2016 and who saw it coming // some saw it coming

or—

it is 2020 and the women in Beirut are a sea // I mean my country // looks beautiful in red // I mean I look beautiful in red // I mean this country likes me in red

or—

it is every year and my country is taken // I mean my country is stolen land // I mean all my countries are stolen land // I mean sometimes I am on the wrong side of the stealing // my country is an opening // I mean bloom // I mean bloom not like flower // but bloom like explosion // my country is a teacher // I mean do you want to see my passport // I mean do you like my accent // I mean I stole them // I mean I stole them // I mean where do you think I learned that from

Inhabiting time proves no less barbarous for the poets than the land that is denied to them. Wars of extermination enforce their own rhythms that render their victims helpless in their confrontation with their unnatural deaths. Poetry counters and resists the temporalities of land theft and the brutalities that are meted out on Palestinian bodies and livelihoods. Time for Palestinian poets is a country.

Amman-born Noor Hindi writes about her father drawing and redrawing the map of Palestine.

I Once Looked In a Mirror But Couldn’t See my Body

(Ekphrastic poem, after ‘The Persistence of Memory’ by Salvador Dalí after Mahmoud Darwish)

Noor Hindi

I Once Looked In a Mirror But Couldn’t See my Body

(Ekphrastic poem, after ‘The Persistence of Memory’ by Salvador Dalí after Mahmoud Darwish)

Noor Hindi

It didn’t feel much different

than walking

through this country, citizen

less & carrying

a history. Somewhere

is my body

alone & watching

my father

in the middle of the night

drawing & redrawing

a map of Palestine, green

ink—

& it hurts

& it hurts

& it hurts

& it hurts

What is Palestine if not the olive tree growing on my father’s tongue

What is Palestine if not the olive tree growing

What is Palestine if not the olive

What is Palestine

What—

Somewhere is a clock.

Melting.

Lifetimes melt in the fire of the military erasures of Palestine as a land and a people.

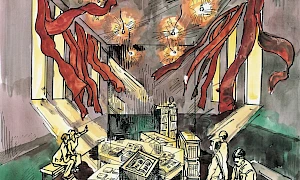

Since the Nakba of 1948, Palestinians have been living with forms of violence that repeat and multiply, wherein Palestinian immiseration and the losses incurred of homes, kin and ecologies relentlessly destroy their lives. Images repeat, the discourse that legitimizes the violence they endure repeats, the language used to describe them repeats. Thus, a poem from the past remains relevant, as if it’s written in the present. Such is the case with Gaza-born Kamal Nasser’s poem ‘The Green Light’, about an unnamed city – perhaps Gaza.

The Green Light

Kamal Nasser

trans. Rana Issa

The Green Light

Kamal Nasser

trans. Rana Issa

I walk through the city of the dead

trampling over my shadow

I beg the slain ruins for life

in my land and my people.

This silence, this slumber terrifies me

how the pale casts its long shadow, it frightens me, as if it’s all that remains

of the corpses

embracing me

coiling around me … should I walk in the city of the dead

⬳⬳⬳

No

I did not come to bring life,

to my city, and I did not come to re-member the fragments.

The big game collapsed

in the playing fields of the endgame.

Shame offered prayers at the funeral.

The banquet of conflict is whored

made wanton by the propagandists

and the patrons.

Feeble she stood erect … bringing crumbs

Crumbs will not satisfy

Crumbs will not satisfy

⬳⬳⬳

When I walk in the city of the dead

trampling over my shadow

I beg the slain ruins for life

in my land and my people

I find everything. Died.

⬳⬳⬳

And when I walked through the city of the dead

desolation killing me

my I wounding me

proud impotence marching away from survival with me in procession,

I caught a specter obliterating the emptiness,

creeping like light on the world.

I found myself traversing the vast expanse

walking behind it

I found myself crossing through life

walking like faith itself, in the city of the dead…

The torment of existence surging through me

I glimpsed a child … one year old.

15/10/1965

In 2017 Lena Khalaf Tuffaha wrote a poem that signalled genocidal violence before the advent of this latest and accelerated ongoing genocide.

Running Orders

Lena Khalaf Tuffaha

Running Orders

Lena Khalaf Tuffaha

They call us now,

before they drop the bombs.

The phone rings

and someone who knows my first name

calls and says in perfect Arabic

‘This is David.’

And in my stupor of sonic booms and glass-shattering symphonies

still smashing around in my head

I think, Do I know any Davids in Gaza?

They call us now to say

Run.

You have 58 seconds from the end of this message.

Your house is next.

They think of it as some kind of

war-time courtesy.

It doesn’t matter that

there is nowhere to run to.

It means nothing that the borders are closed

and your papers are worthless

and mark you only for a life sentence

in this prison by the sea

and the alleyways are narrow

and there are more human lives

packed one against the other

more than any other place on earth

Just run.

We aren’t trying to kill you.

It doesn’t matter that

you can’t call us back to tell us

the people we claim to want aren’t in your house

that there’s no one here

except you and your children

who were cheering for Argentina

sharing the last loaf of bread for this week

counting candles left in case the power goes out.

It doesn’t matter that you have children.

You live in the wrong place

and now is your chance to run

to nowhere.

It doesn’t matter

that 58 seconds isn’t long enough

to find your wedding album

or your son’s favorite blanket

or your daughter’s almost completed college application

or your shoes

or to gather everyone in the house.

It doesn’t matter what you had planned.

It doesn’t matter who you are.

Prove you’re human.

Prove you stand on two legs.

Run.

The repetitive temporalities of Israeli violence threaten to normalize and fetishize the victimization of Palestinians. This prompts Yafa poet Sheikha Helawy to write ‘Nakba’.

Nakba

Sheikha Helawy

trans. Fady Joudah

Nakba

Sheikha Helawy

trans. Fady Joudah

My mother is three years younger than Nakba.

But she doesn’t believe in great powers.

Twice a day she brings God down from his throne

then reconciles with him

through the mediation of the best

recorded Quranic recitations.

And she can’t bear meek women.

She never once mentioned Nakba.

Had Nakba been her neighbor,

my mom would’ve shamelessly chided her:

‘I’m sick of the clothes on my back.’

And had Nakba been her older sister,

she would’ve courted her with a dish

of khubaizeh, but if her sister whined

too much, my mom would tell her: ‘Enough.

You’re boring holes in my brain. Maybe

we shouldn’t visit for a while?’

And had Nakba been an old friend,

my mom would tolerate her idiocy

until she died, then imprison her in a young picture

up on the wall of the departed,

a kind of cleansing ritual before she’d sit to watch

dubbed Turkish soap operas.

And had Nakba been an elderly Jewish woman

that my mom had to care for on Sabbath,

my mom would teasingly tell her

in cute Hebrew: ‘You hussy,

you still got a feel for it, don’t you?’

And had Nakba been younger than my mom,

she’d spit in her face and say:

‘Rein in your kids, get’em inside,

you drifter.’

Nablus-born Zakaria Mohammad reflects on the boredom and normalization of this catastrophic situation that repeats: ‘a day after another day / another unchanging day / the days replicate in our time / what is different between them is the measure of misery added to our memory / that is laden with older burdens’. This repetitive temporality cages Palestinians in an eternally catastrophic present of nakba, the condition of Palestinian immiseration and erasure. Palestinian poets write against the temporalities of war and struggle to force open pockets of resistance through insisting on living, loving and the right to an everyday. As martyred author and political spokesperson Ghassan Kanafani (born in Akka in 1936) expressed, the notion of resistance poetry in occupied Palestine aligns with an everyday practice of asserting Palestinian identity in the face of cultural, social and political erasures enforced by the Israeli settler regime.9.See Ghassan Kanafani, ‘Selection from Resistance Literature in Occupied Palestine, 1948–1966 by Ghassān Kanafānī’ (ed. Johanna Sellman, trans. Shadi Rohana), Journal of Arabic Literature, vol. 55, 2024, pp. 168–88.

The predicament of Palestinians forces new metaphors where time gives way to the corporal, and political domination expresses itself in psychosomatic signs. The ongoing genocide in Gaza made this relation blatant for me, as I experienced my body fall apart, and learned from my friends that their bodies too are not faring any better than mine. Genocidal time disrupts the fulfillment of basic needs like sleep and food and causes our tempers to become so unstable as to affect our interpersonal lives. We felt fatigued from the first massacre, and many of us labour hard to reject the normalization of Palestinian death. Colonial time is felt by our bodies, and it is through our bodies that we look for ways to resist their brutality. In the earlier poem ‘I Once Looked in a Mirror but Couldn’t see my Body’, Noor Hindi writes: ‘Somewhere / is my body / alone & watching / my father / in the middle of the night / drawing & redrawing / a map of Palestine, green / ink—’. We turn inwards, towards our bodies, and listen to what hurts, to find ways to describe the physical and mental onslaught of colonial time. Najwan Darwish captures these often invisible processes through the poetic displacement of time onto his heartbeat. In listening to his heart’s rhythms, Darwish registers the ruination he is witnessing beyond his perishing body.

Nothing More to Lose

Najwan Darwish

trans. Kareem James Abu Zeid

Nothing More to Lose

Najwan Darwish

trans. Kareem James Abu Zeid

Lay your head on my chest and listen

to the layers of ruins

behind the madrasah of Saladin

hear the houses sliced open

in the village of Lifta

hear the wrecked mill, the lessons and reading

on the mosque’s ground floor

hear the balcony lights

go out for the very last time

on the heights of Wadi Salib

hear the crowds drag their feet

and hear them returning

hear the bodies as they’re thrown, listen

to their breathing on the bed

of the Sea of Galilee

listen like a fish

in a lake guarded by an angel

hear the tales of the villagers, embroidered

like kaffiyehs in the poems

hear the singers growing old

hear their ageless voices

hear the women of Nazareth

as they cross the meadow

hear the camel driver

who never stops tormenting me

Hear it

and let us, together, remember

then let us, together, forget

all that we have heard

Lay your head on my chest:

I’m listening to the dirt

I’m listening to the grass

as it splits through my skin…

We lost our heads in love

and have nothing more to lose

Incidents of brutalization leave their marks on Darwish’s body and lodge themselves in the rhythms of his heart. With Nasser Rabah’s ‘In the Endless War’ we encounter the effects of yet another war in Gaza (prior to genocide) on the terrified bodies of inhabitants. Bodies mangle with the ruined spaces of Gazan lives; hearts stop and start while hands keep searching for the necessary documents that are legal proof of lived life; tears and ceilings fuse, and the distance between two buildings is the space of one hour, ‘a building embraced by a missile and another/ one opening its chest for the last person gasping on/ a street about to exit history instantaneously. As for the minute, no minutes in war, time is rather measured by martyrs.’ In Gaza it is no longer possible to discern the shapes of the world with its organisms and matter.

The history of Palestinian poetry belongs to the legacy of Palestinian poets targeted through imprisonment and assassination by the colonizers – British as well as Israeli – that goes as far back as Tamra-born Nuh Ibrahim (a poet who was imprisoned several times by the British for his poetry, and who was killed in battle in 1938), and includes famous poets like Mahmoud Darwish, Tawfiq Zayyad, Nasser Abu Srour, Dareen Tatour, and many others. Poets, too, sometimes die fighting. Such was the fate of Abd al-Rahim Mahmoud, a poet who died in the battle of al-Shajara in 1948, famous for ‘The Shaheed’ (1939), which begins: ‘I carry my soul in my palm / And deliver it in the valley of death / For either a life that delights my friend / Or a death that vexes the enemy’.10.Translation by Rana Issa. Other poets die as civilian casualties, victims of Israeli violence that is committed to striking civilians and civilian infrastructure. During this war we mourned the loss of Gazan poet Heba Abu Nada, killed on 20 October 2023. We also mourn the loss of poet and scholar Refaat al-Areer, who was most likely assassinated in a targeted bombing along with six members of his family (with three more members wounded) in December 2023.11.On al-Areer’s assassination, see the investigation conducted by Euro Med Monitor, ‘Israeli Strike on Refaat al-Areer Apparently Deliberate’, 8 December 2023, euromedmonitor.org. Al-Areer was punished a second time, after his death, through another assassination in April 2024 targeting his daughter Shaima, her husband, and her infant son.12.See Dan Sheehan, ‘Refaat Alareer’s daughter and grandchild have been killed in an Israeli airstrike.’ Literary Hub, 26 April 2024, lithub.com. We mourn at least forty-five poets and writers who have died in Gaza since the beginning of this war and acknowledge other poets we have undoubtedly lost but who are not yet accounted for.13.See ‘Israel has killed 45 writers and artists in Gaza since Oct. 7– PCBS’, Jordan News, 14 March 2024, jordannews.jo. Most of them were targeted by the Zionist entity not because they were poets, simply because they were Gazans.

Since the Oslo Accords (1993/95), Palestinian poetry has borne witness to land annexation, aerial bombing, imprisonment, and their accompanying feelings of deep alienation, anger and perplexity. In the words of Gazan Marwan Makhoul: ‘To write non-political verse / I must listen to the birds / To hear the birds / The plane must hush’. In contemporary Palestinian poetry, the poetic subject writes of the war of decimation, to grapple with staring death in the face, as a daily travail. This is a far cry from the high poetic voice of Palestine’s most famous poet, Al-Birwa–born Mahmoud Darwish, who envisioned himself as a prophet and understood his poetic vocation as representative of Palestinian struggle.

In Jerusalem

Mahmoud Darwish

trans. Fady Joudah

In Jerusalem

Mahmoud Darwish

trans. Fady Joudah

In Jerusalem, and I mean within the ancient walls,

I walk from one epoch to another without a memory

to guide me. The prophets over there are sharing

the history of the holy … ascending to heaven

and returning less discouraged and melancholy, because love

and peace are holy and are coming to town.

I was walking down a slope and thinking to myself: How

do the narrators disagree over what light said about a stone?

Is it from a dimly lit stone that wars flare up?

I walk in my sleep. I stare in my sleep. I see

no one behind me. I see no one ahead of me.

All this light is for me. I walk. I become lighter. I fly

then I become another. Transfigured. Words

sprout like grass from Isaiah’s messenger

mouth: ‘If you don’t believe you won’t be safe.’

I walk as if I were another. And my wound a white

biblical rose. And my hands like two doves

on the cross hovering and carrying the earth.

I don’t walk, I fly, I become another,

transfigured. No place and no time. So who am I?

I am no I in ascension’s presence. But I

think to myself: Alone, the prophet Muhammad

spoke classical Arabic. ‘And then what?’

Then what? A woman soldier shouted:

Is that you again? Didn’t I kill you?

I said: You killed me … and I forgot, like you, to die.

Referred to in the poetry of Heba Abu Nada, Samer Abu Hawwash, Noor Hindi, and many others, Darwish’s legacy seems to be conjured to be venerated, yet also in that his voice no longer suffices in the present moment. Death has become too voracious for the eloquence and self-confidence that belongs to an earlier time of revolution and literary renewal. What has changed since Darwish’s time is a weakened Palestinian political leadership as a result of the Oslo Accords, which has led effectively to the politicide of Palestinians. In these circumstances, poetry and writing become a refusal to be silenced by the fact of death.

While Darwish acts as the towering literary figure that newer Palestinian poets both celebrate and altercate with, he, too, displaced space onto time. In Jerusalem, the poet walks along streets, from ‘time to time without remembrance to guide me’.14.In variation with the previous translation of this poem by Fady Joudah, I give my translation inline here. Lost in the temporal layers of the city, Darwish likens himself to the prophets who walked these streets before him. Today’s poets do not wish to become prophets, and their poetry rejects its oracular function. Poetry today inverts the relation to the collective. Rather than speak on behalf of Palestinians, poets now struggle to find ways to overcome their isolation, work through their grief and reconnect with their community. They dissolve their artistic function into the antiheroic; one of the people, not speaking for them. Poets’ lives, like all Palestinians’ lives, are precarious; they lack adequate means to end the onslaught of violence they confront. In such conditions, representational politics becomes a toxic lie covered up by the garbage of language that so bothered Walid Daqqa, and still vexes Palestinians to this day.

In the face of overwhelming extermination, Palestinian poets insist on their right to life. The wager is on the capacity of Palestinians to overcome their brokenness and to pursue possibilities for the exercise of freedom. Yet the same words that poets work with are used to justify the murder of Palestinians in international media and diplomatic forums. In Noor Hindi’s poem, ‘the shell of a cactus fruit’, the poet samples Benjamin Netanyahu’s speech at a UN General Assembly meeting in order to reclaim the depiction of Palestinian loss.

the shell of a cactus fruit

Noor Hindi

the shell of a cactus fruit

Noor Hindi

Dear K,

Have you dreamt of pomegranates this week? All the time you would talk of the pomegranate trees that reflected from your grandfather’s eyes. If history is a woman with gentle hands pouring black tea, let there be sunlight, a soft chair, a young Palestinian boy entering his home for the first time. How remarkable is that? Let the woman be Jewish, and let there be nothing political about the way she yearns for her son’s safety, about the years between 1948 and 1974, years your grandfather spent mourning the dirt he used to plant those pomegranate trees. In this version of history, there is some forgiveness. Come in, come in she beckons you. Everything will change. Maybe you remind her of her son, how you both share the same olive-skinned complexion. You enter.

Dear K,

All this is real. You tell me stories. You repeat did you get that? and do you hear me? like I won’t believe you. You hate the way I interrupt Al Jazeera, the way I ask questions. Your body is collapsed on our tired beige couch. Every hour we talk makes me wonder if you’ll ever make eye contact. Will you look at me? Palestinian habits die because Palestinian bodies are dying – are dead. It happens every day. They couldn’t care less about your grandfather, how he spent so many of his days staring at a ceiling, inhaling cigarette smoke, relying on the United Nations for food, for shelter. Year after year, you hovered around him – unbreakable.

Dear K,

In a photo, you stand next to him, wearing a small smile, dress pants, and a sweater. You told me once that he would smack fear right out of you. Is this why you have a history of hostility? Mom says you wrote love letters to her. She ripped each and every note you ever gave her, then burned them. This conflict rages. I wonder how much of you existed in those pages.

Dear K,

Imagine a day in the life of a 13-year-old Palestinian boy, I’ll call him . throws a rock at an Israeli tank because Israel will not allow more than two to four hours of electricity a day for residents in Gaza. An Israeli soldier catches , lines him up in front of a wall, then threatens to shoot. thinks about clouds, how he’d one day like to greet them. was you, is you. In a dream, my great-grandmother flees her home, a pot held over her head to keep from the sun. Perhaps if she had thirsted a little less your love would be greater, stronger, more profound.

Dear K,

Remember the cactus fruits you would always bring home? The shell of the cactus fruit has hundreds of hair-like thorns hiding under its surface. You always knew the exact place the blade of the knife must slice to open the sweet part of the fruit. Is that not love?

Like a plant in photosynthesis, Hindi transforms language dioxide – to return to Walid Daqqa’s words, and to the title of this piece – into meaning. Photosynthetic linguistic transformations find a powerful counterpart in the practices of resistance, equally poetic in their imaginative subversion of the settler-colonial machinery of Israeli violence.

Daqqa gives me another key to unpack the function of poetry in Palestine today: his active resistance, from prison, against the Zionist state. From Baqa al-Gharbiyye, Daqqa was martyred on 7 April 2024 in the prison in which he was first incarcerated on 25 March 1986. He died from medical neglect and torture at the age of sixty-two, having spent the entirety of these decades serving time between all of Israel’s prisons. Daqqa became known from behind bars as a political theorist, literary writer and illustrator. Together with his wife Sanaa, his daughter Milad (in Arabic, Birth) was also born while he was behind bars, by smuggling his Palestinian sperm from the Israeli jail, a subversive practice that has so far resulted in 181 Palestinian children born to incarcerated fathers.

I am concerned with two of Daqqa’s works in particular: Consciousness Molded or the Re-identification of Torture, on how Israeli prisons work, and a children’s tale, The Oil’s Secret.15.Consciousness Molded or the Re-identification of Torture (صهر الوعي:او إعادة تعريف التعذيب), Doha: Arab Scientific Publishers, 2010. The Oil’s Secret (حكاية سر الزيت), Gilboa Prison, 2017. Both texts give a brutal depiction of the reality of Zionist occupation as seen from the perspectives of a prisoner and a young teenager, respectively. I wanted to read The Oil’s Secret to my teenage son, but was struck by how it seems impossible to translate the occupation to a child who has neither experienced such violence, nor yet been adequately initiated into the history of our people.

I associate Daqqa’s voice reaching us in spite of his prison walls with the poems by writers from Gaza that now reach us from behind the watertight siege and the genocide – with the words of Heba Abu Nada and Refaat al-Areer, or of the anonymous poets writing on the rubble of Gaza’s homes, or Gaza residents Maryam Qawash, Heba Agha and Sumia Wadi who continue to publish on social media at the time of writing. Their poems, which we read too often after their deaths, are kin to the children who are born to imprisoned freedom fighters, and to books penned and drawings smuggled out of the Israeli prison complex.

The poetic imagination enables leaps that overcome the enforced logic of Israeli erasure, where metaphoric overcoming is embodied in resistance practices on the ground and not only in language. It is an imagination that informs such practices of resistance, like the Gilboa Prison break of 2021, when six Palestinian prisoners escaped by digging a tunnel with a spoon. The Israelis pronounce all these acts – poetic and practical – on a par with one another, in order to justify their application of severe force on the Palestinians who perform them. The Israeli settler regime brutalizes the subjects who make these acts, along with their families; any attempts at self-narration or self-determination are punished under the false assumption that force will weaken the will for liberation.16.Dareen Tatour spent three years in and out of jail for a poem she wrote. Sperm smugglers are very heavily punished, with fathers’ sentences being extended and their babies being refused official registration upon birth. Armed resistance leads to the geocoding of Gaza, to the bombing of Jenin, Tul Karm, Nablus… The list of seemingly infinite acts of cruelty goes on. Regimes of brutalization are never able, it seems, to learn the simple if uneasy lesson that the wretched of this earth never tire of seeking their liberation.

Palestinian poets work through their dispersals and dispossessions so new beginnings can manifest, even without the appearance of an end. Through their words they intervene in the repetition and normalization of the nakba’s eternal presence. Palestinian poetry is not alone in such a pursuit of new beginnings: its voices connect with the labour of liberation practiced by other wretched peoples, with the writings of Black poets, Arab poets and the colonized else- and everywhere. To close with the words of exiled Egyptian author Haytham el-Wardany on Gaza: ‘to speak any other language than the language of the dead today is to participate in the ongoing crime. The dead. The unburied dead. They can never be annihilated, even though our enemy continues to be victorious. Their language is that of the tiniest imperishable life forms, persistently sending signals, from beneath the earth.’17.Haytham el-Wardany, ‘Labour of Listening’, Minor Literature[s], 23 July 2024, minorliteratures.com.