A walk-through the exhibition ‘MONOCULTURE – A Recent History’ at M HKA (Antwerp), with Nick Aikens and Nav Haq in conversation

Soviet Corn Campaign Poster, За велику кукурудзу! (For Great Corn!), 1962. Published by Міністерство культури УРСР (Ministry of Culture of The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic). Image: M HKA.

Nick Aikens, co-organiser of the two-day conference “Considering Monoculture" in conversation with Nav Haq, curator of the exhibition MONOCULTURE – A Recent History.

Nick Aikens: Where did the idea come from to stage an exhibition on monoculture, and how did you begin your research?

Nav Haq: Exploring the notion of ‘monoculture’ was related to thinking about the stagnation of the ‘multiculturalism’ debate. Like my conceptualisation of the Gothenburg Biennial in 2017 on the subject of secularity, which opens on to questions of ethics and cohabitation, the idea of monoculture is a way to talk about many interconnected things at the same time – from agriculture and linguistics to ideology and officially sanctioned conceptions of culture. Monoculture gives a name to what Chantal Mouffe repeatedly referred to as the ‘forces of homogeneity’ at the ‘Considering Monoculture’ conference. In a societal sense, monoculture means cultural homogeneity, and it felt urgent to address and raise awareness of something that is increasingly prevalent.

Nobody, to my knowledge, had made a map of monocultures, so I had to sort of invent one. The first step was a complex mapping exercise, looking at different understandings and manifestations of monoculturality. It was hands on, with massive sheets of paper, which I filled in with artists, ideologies, ideas and practices, as well as all kinds of case studies – then it just kept growing. It was particularly relevant to chart the relationship of art to ideology – so Socialist Realist art in the context of the Soviet Union, to give one example, running into the Corn Campaign, which proliferated monocultural farming in that region. I spent a year or so developing this map, before translating it into an exhibition.

NA: How did you form this? Were there specific books that informed you, specific historical narratives of the twentieth century? Nationalist Socialism, eugenics, Négritude immediately come to mind…

NH: It felt important early on to approach monoculture from a philosophical perspective, rather than a purely epistemological one. I am more broadly interested in bringing more philosophical dimensions to the projects we undertake at the M HKA. There also seemed to be a natural correlation with psychoanalysis, in relation to some of these historical case studies. Else Frenkel-Brunswik [Polish-Austrian Jewish psychologist] was a central thinker for viewing monoculture through the lens of ambiguity from the start. It became clear that this was not a new subject for artists, who have either explored forms of monoculturality, or been guided by it, even if they are not necessarily using the term directly.

NA: How did you come across Frenkel-Brunswik, who is relatively unknown?

NH: It was when I was undertaking my research for the Gothenburg Biennial that I came across her work. I didn’t refer to her for that particular project, but she became a significant reference for ‘Monoculture’. At the very core of this exhibition, and also in the project on secularity, are questions of equality and freedom, ultimately asking: What kind of society do we want? Attached closely to this – and what L'Internationale is largely concerned with – is the question of the role of art and cultural institutions in society.

NA: Essentially, the exhibition presents a history of ideas and ideologies of the twentieth century. Yet there is no clear trajectory, no chronology. There are certain groupings - relating to language or agriculture, for example; historical moments like the section that addresses Négritude, or intellectual projects as is the case with the publications around psychoanalysis. How did you structure the exhibition and decide on these groupings of works?

NH: It was about combining positions that seemed to make sense thematically, and that are connected. The word ‘monoculture’, as we learned from the conference, comes from agriculture. This relationship to agriculture recurs throughout and is also centrally located to the exhibition. So most people will experience Åsa Sonjasdotter’s work on the industrialisation of agriculture and the development of monocultural farming practices, which sits in proximity to N. S. Harsha’s work reflecting on the high suicide rate among farmers in India who have been forced to adopt monocultural techniques. The idea of ambiguity was crucial as well, as we’ll discuss I’m sure, and from there came building blocks into other case studies and practices.

As always, there is a lot of intuition. Then, there are pragmatic questions, because individual artworks need certain conditions like space or light, along with the given architecture. At M HKA, when you come up the stairs to the exhibition space, you arrive right in the middle – and I like this quality of starting in the middle. It felt important not to lead people by the hand with the route, and experientially speaking, to relate the spatial design to the idea of monoculture, thus privileging people’s subjectivity.

Entartete Kunst, including works by (L-R): George Grosz, Lovis Corinth, Karl Hofer. Photo: M HKA.

NA: Yes, the architecture of M HKA is really constructive for this show. The space is asymmetrical, and you don’t present a progression from a beginning to an end – people have to figure out a journey for themselves.

NH: Exactly. Still, we had to transform the space quite a bit, in order to create different zones that would feel as ‘natural’ as possible. I wanted walls to look like solid walls, as if they had always been there. But there is a differentiation between the white walls and the wooden walls. in my mind are more connected to this notion of ambiguity.

NA: So the white wall, the white cube, is also a form of monoculture?

NH: Yes, broadly speaking. The white walls are the background for case studies of monoculture – from the dominant ideologies of the twentieth century to attempts at artificial universal languages, like Esperanto. The wooden walls are the backdrop for works by Carol Rama and Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin, as well examples of Entartete Kunst [so-called ‘Degenerate Art’] paintings, or the writings of Frenkel-Brunswik and Ursula K. Le Guin. There are exceptions to the rule, but that was the basic principle.

NA: Let’s turn to some specific examples in the exhibition to understand your approach to relating different histories and ideas. For example, in one section, material related to the Non-Aligned Movement appears close to Jonas Staal’s Freethinkers’ Space (2008–ongoing). Nearby there is Francis Fukuyama’s book The End of History and the Last Man (1992). How were these constellations conceived?

Foreground: Jonas Staal, Vrijdenkersruimte Vervolgd (Freethinkers’ Space Revisited), 2012. Photo: M HKA, Wim Van Eesbeek.

NH: With the Freethinkers’ Space, and the connection with artefacts related to the Congress for Cultural Freedom, I learned about this through Jonas Staal, at the conference he organised in Amsterdam in early 2020 on propaganda and art. The Congress for Cultural Freedom, was used for Cold War-era soft power in the US – for example with the exhibitions of Abstract Expressionism that toured the world. So, there was a relationship around art and exhibitions being used for propaganda – and there were many examples of this in the twentieth century. Close to Staal’s work, there are projects related to censorship and freedom of expression, and in a certain way to do with culture wars, which is intended to mirror the artefacts of Belgian and American culture wars at the very opposite ends of the exhibition. For me, Fukuyama also brings this idea of culture war, but in the geopolitical sense, rather than on a national scale, and this sits in relation to artefacts from the Non-Aligned Movement. Sille Storihle’s film The Stonewall Nation (2015), exploring Don Jackson’s attempt to create an exclusively gay colony in California in 1970, draws out the subject of nationhood and nation-building.

Yes, because Benedict Anderson’s 1983 book Imagined Communities also appears here. That is in relation to Maryam Najd’s work Grand Bouquet (2010–12), which is also about nationhood. It brings all the official national flowers of the world into one image. Many of the species selected are non-native, which brings up the question of migration, which is a key aspect of Staal’s Freethinkers’ Space in the sense that it looks at how political positions view culture and censorship, including examples of supposed ‘Islamic censorship’ as the result of ‘political correctness’.

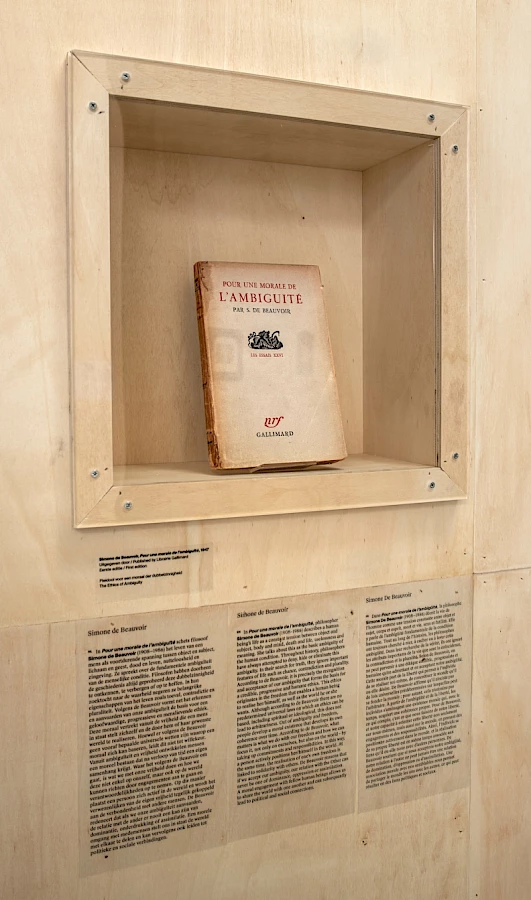

Simone de Beauvoir, Pour une morale de l’ambiguïté (The Ethics of Ambiguity), 1947. Photo: M HKA, Wim Van Eesbeek.

NA: First edition books are a major part of the show. You have given them a special treatment, inset into the walls, with a glass covering, so that the books in a way become artworks or images. Did you want to set up a relationship between them and the artworks, to make a catalogue or an inventory of these ideological or theoretical positions?

NH: We always described them as artefacts, so I don’t think of them as artworks. But they are exhibited in a way that is not typically seen in a contemporary art museum. Some of the ideas that I wanted to introduce are not always present in artworks, and I don’t like the idea of artworks illustrating ideas either. Still, I wanted to bring philosophical thought into the dialogue.

I still think that there is something exceptional about the experience of an original object as part of a visit to a museum. For example, with the posters from the Non-Aligned Movement – more specifically from OSPAAAL (Organisation of Solidarity for the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America) – to see the originals is somehow more meaningful than seeing reproductions. They have a beautiful material quality, and are very artistic. The other important thing is that all of these items become assets to the museum, as we acquired them as part of our research. So, I hope this can signal that these can be research tools for anybody, eventually. A big part of the thinking with this exhibition is how we can archive and hold the material so it becomes useful in future to interested artists and researchers. There is also material from the exhibition research that we didn’t exhibit, but that we still have.

Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin, Global Digestion, circa 1980–2007. Photo: M HKA, Wim Van Eesbeek.

NA: Let’s move to the Alptekin room. This is one of the most fascinating rooms for me, precisely in trying to understand the relationship you’ve set up between ideas and images, or ideology and art let’s say. We’ve got Simone de Beauvoir’s book The Ethics of Ambiguity (1947), we have Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, Hannah Arendt, Julia Kristeva, and then there’s the work by Alptekin and Carol Rama. This room feels significant both for your proposition for the exhibition and for your ideas around ambiguity, which you explore in your recently edited volume The Aesthetics of Ambiguity. It is the only space in the show where we are enclosed in wooden walls, enclosed in walls of ambiguity, let’s say. It has lower lighting – I imagine because of the light requirements for the Carol Rama works, but you have the sense of being in a much more intimate, reflective space.

NH: Three publications with contributions by Frenkel-Brunswick are displayed in this room: The Authoritarian Personality (1950), which she co-authored with Theodor Adorno and Daniel Levinson, as well as her texts ‘Personality theory and perception’ (1951) and ‘Environmental Controls and the Impoverishment of Thought’ (1953). They’re really scientific papers, but surprisingly accessible to the untrained reader, like myself. They outline the developments of her thinking on ‘ambiguity tolerance and intolerance’. This was her way of exploring ethnocentricity and the authoritarian mind. Her central thesis is that our levels of tolerance towards ambiguous things are connected to our social outlook. ‘Ambiguity’, for Frenkel-Brunswick, could be perception of another person – how tolerant we are when encountering someone of, say, ambiguous race or gender – and how desirable or undesirable we find that experience. But, significantly, it could be other ambiguous things or experiences, which brings us into the realm of aesthetics. I also placed art in the category of ambiguity, as something that can reflect and even influence people’s tolerances. Someone who is ambiguity intolerant typically possesses the characteristics of the monocultural mind. And the more ambiguity tolerant we are, the more socially inclusive we are, according to the evidence. The example of Entartete Kunst – holding up avant-garde art as an aberration – is a crucial case study of ambiguity intolerance in the art-historical context. It offers a window onto extreme intolerance in society as a whole. Her ideas directly connect the liberalisms of perception, cognitive function and tolerance, and open up the question of the emancipatory potential of ambiguity as something that can influence tolerance. But of course, what is considered ambiguous is relative. The presence of Frenkel-Brunswick’s ideas here is symbolic, but it’s important that they are included. It’s actually rather hard to get hold of her books, so now we have them as research assets.

NA: So how would you say this is symbolic in a way the other books weren’t? Because she’s not putting forward an ideology as such.

NH: No, but her ideas are very much born out of the experience of escaping extreme ideology. Many pioneering psychoanalysts were Jewish people living in Austria or places occupied by the Nazis. They fled – for example Freud went to England, and so did Melanie Klein. There are some people who consider psychoanalysis as something that escaped the Holocaust. Not surprisingly, psychoanalysts wanted to explore the human mind, including its extremities. There are these two sides to science in the early twentieth century – the pseudoscience of eugenics and ideas of ‘racial hygiene’, and the science that flourished after escaping those extreme experiences.

NA: Eugenics appears in the adjacent room.

NH: Yes, and all of the books in this Alptekin/Frenkel-Brunswick room are in contrast. Freud’s book Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1921), and Arendt, of course, tell us something about extreme ideology and its public influence. It is interesting that during the 1940s both psychoanalysis and philosophy, in the case of de Beauvoir, are unpacking the notion of ambiguity. De Beauvoir is another key figure for the exhibition because her work is really about freedom, which connects with artistic freedom.

Carol Rama. Photo: M HKA, Wim Van Eesbeek.

NA: If I look at the Carol Rama works in relation to de Beauvoir’s publication The Ethics of Ambiguity, are you pointing to Rama’s work as an exemplar of ambiguity?

NH: Certainly. With de Beauvoir, there can be a misunderstanding around existentialism, which is too often understood as nihilistic. She clarified that it is actually about emancipation. To really understand ourselves as human beings, we are not guided by ideology, whichever that might be, and we’re not guided by some higher power, but we’re unresolved as individuals, we are fundamentally ambiguous. Only when we understand this, can we use ambiguity as a starting point for emancipation. I have a lot of sympathy for this idea. For me, Carol Rama is someone who really lived this, seeking that freedom. She makes this art in the era of fascism in Italy. Her work is about exploring the fundamental ambiguity of the body, sensuality, physicality, and ideas like abjection. She is a brilliant example of someone who was really practising artistic freedom, which mirrored her everyday life.

NA: Then Alptekin’s work Global Digestion (1980–2007), which consists of hundreds of photographs of types of toilets – why is it placed here?

NH: I found Alptekin’s work bound several things rather succinctly. There’s a lot of exhibits that are doing several different things at once here, in my mind. I found this to be a good position for Global Digestion because, firstly as a work about human digestion, it connects directly with the work of Harsha and Sonjasdotter on food production. It relates to Nazism as it talks about the concept of hygiene. It relates to the idea of abjection in Julia Kristeva’s writing, which appears in this space too, and finally it relates to globalisation, which we see in the nearby grouping that explores liberal capitalism. Alptekin was an artist fascinated by the conditions created by globalisation. He took these photos during his travels around the world over several decades.

NA: Reading The Aesthetics of Ambiguity, which is somehow an accompaniment to this exhibition, something came up that I’m trying to negotiate; that is, the relationship between ambiguity and autonomy. Where autonomy, in the modernist sense insists on a separation between art and politics, from a political position, ambiguity also evokes a certain detachment from ideological positions. It seems in this room you’re making a proposition between forms of ideology as they’re put forward by certain thinkers and political projects, and the space that art can occupy, with artists like Rama and Alptekin, which is more like the space of ambiguity. So the central proposition is that the capacity of art to occupy or create a space of ambiguity makes us more open to diverse political perspectives. Art that is put at the service of a political project is not included in the show, like the Black Panthers for example. Occasionally there is a direct correlation between the artworks and a political project, but overall you seem to be making a case for separating those. So I’m wondering about your position on autonomy, as art being drawn back from direct engagement in a political agenda.

NH: When you say ‘autonomy’, I assume you use it in a Kantian sense. That takes us into another interesting philosophical conversation. I would myself use the word secular. The condition of art is a reflection of the process society has gone through in terms of secularisation. I don’t agree that what has been described as autonomous is somehow purposeless; rather, art is no more autonomous than science and medicine, or politics, say, because they’ve gone through the same process of secularisation, and these of course have an important use value. This is a well-established analysis, including in art. For me ambiguity is not purposeless either; on the contrary, I think there is a societal use value here, and this is what I’m trying to investigate. You’re right to say that in the exhibition we selected examples where art is instrumentalised. I don’t have any issue with art being utilised in emancipation movements, but I do think then that these movements shouldn’t discriminate against practices and people that sit outside of their own cultural conception. When I talk about secularisation, in principle it also allows diverse practices and practitioners to coexist. Contemporary art can exist alongside more traditional art practices connected to belief systems, for example. Ambiguity – aesthetically, methodologically or ontologically speaking – can and has been part of political or societal projects, in all kinds of ways. There remains a use value there, and this can connect directly to the question: What is an institution for? Perhaps it’s to make people more tolerant of ambiguity.

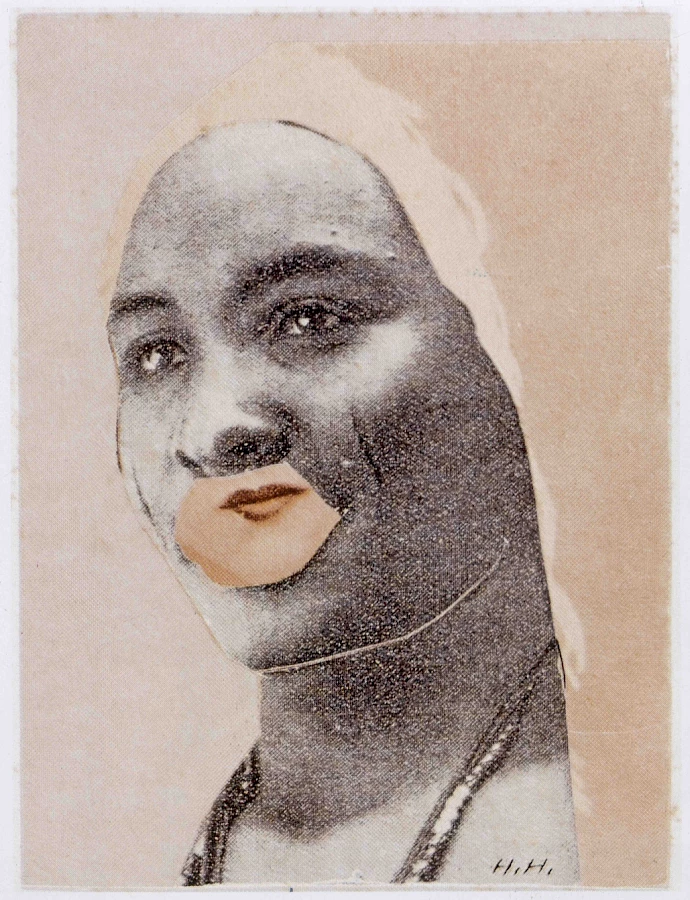

Hannah Höch, Mischling (Mixed Race), 1924. Photo: Liedtke & Michel.

NA: Hannah Höch comes in the room next door. Next to this work (Mischling (Mixed Race), 1924), one of the key pieces of the show, we’ve got the eugenics publications by authors such as Eugen Fischer and Hans FK Günther. If the Rama somehow speaks with ambiguity, the Höch is placed as a counter to those extreme positions.

NH: Absolutely. Höch was considered a degenerate artist. What I really like about her work is that she deconstructs the anthropological gaze, which I imagine, in the twenties, was a radical thing to do, and particularly meaningful in the German context. It is necessary to point out that although eugenics is associated with Nazism, many of its roots are elsewhere, in Britain and the US, and the field was then co-opted by the Northern Europeans. Much of this pseudo-scientific research looked specifically at mixed-race people – it seems to me that much intolerance is linked to the experience of ‘the Other’, and the ambiguity of this experience. For many racist people, encountering a mixed-race person is somehow even worse than encountering someone they can categorically judge to be black, because the ambiguity exacerbates their intolerance. Some ‘research’ was made by the Germans on mixed-race people in Namibia when it was a German colony. German colonial history fed into Nazi constructions of racial purity, superiority and ethnocentricity. The reality is that there is no scientific basis for racial difference.

NA: Arguably one of the uncomfortable aspects of the exhibition is the way in which certain political projects and histories are presented in close proximity. First of all, it’s difficult to exhibit a copy of Mein Kampf, or books on eugenics, or the project of Nationalist Socialism. You open yourself up to the critique that you are somehow legitimising that as an ideology. Yet what is in some respect more uncomfortable is when those violent histories are placed alongside emancipatory struggles – in the case of Négritude, for example – without attending to the respective historical conditions and violence of those moments. This could be seen to suggest a form of equivalence between these ideas as simply different examples of monoculture.

NH: I was always conscious of this possible risk because I did not want people to find any moral equivalence between these exhibits. So I aimed to come up with a display that was mindful of this. It was largely a spatial question: how you lay out an exhibition and how people experience things as they move around. For example, I haven’t positioned the section on Nazi ideology directly next to the section on Négritude, while there is proximity between the section on Nazism and exhibits related to colonial history, because German colonial history informed Nazism as a biological movement and the development of ‘race science’. There is another trajectory entirely to Négritude as a postcolonial emancipation movement. I believe members of the public would have said something if they thought some moral equivalence was being made, and nobody has. Also, every exhibit is contextualised with a description text. You can’t control how people think, of course, that is against the logic of how people experience things. But a visitor would have to make a large mental leap to find moral equivalence between many cases here.

NA: We talked about this a lot with the ‘Considering Monoculture’ conference, where we were mindful not to present a monocultural view on monoculture. With the exhibition, there was a wish to present a spectrum of ideologies and histories, without explicitly saying that one is more desirable than another, but rather to understand them as societal manifestations. You don’t present the public with clear or prescriptive ethical judgements, and the exhibition texts are not didactic. So there is a certain ambiguity around the display of these different movements and histories.

NH: I’d say that there are some indirect ethical judgments, but yes that the dialogues between diverse figures are important. I was interested in, for example, putting somebody like Ayn Rand in dialogue with Joseph Beuys. There are more connections there than you might imagine. They ultimately believe in different types of libertarianism, albeit brutal right-wing libertarianism in the case of Rand’s Objectivism, and left libertarianism in the case of Beuys’s Third Way. Beuys is a sort of left libertarian because he believed in emancipation as an individual, but also in having a responsibility to society. Occasionally, judgment can come out of juxtapositions.

It was important not to position myself or the museum as belonging to the typical liberal left often associated with the arts. Partly because, as a liberal person myself, I see that what was once considered ‘liberal’ has now become fragmented. And because I don’t think that museums are only for a liberal left audience. As a public institution, we should be open to society more broadly. The point is to generate tolerance, or perhaps an agonistic space. I don’t particularly see my position as ambiguous; rather, I am trying to ask basic and fundamental questions – to as broad an audience as possible – about what kind of society we might want.

Foreground: Andy Warhol, Birmingham Race Riot, 1964. Background: Kerry James Marshall, Untitled, 1998–1999. Photo: M HKA.

NA: Andy Warhol seems like the artist featured most in the show, which I was surprised by – why Warhol, and why does he appear in several places? You have his Birmingham Race Riot (1964) print, so you’ve also used him to reference certain historical moments.

NH: Warhol is an artist who embodies the ideology of liberal capitalism, with a kind of criticality. In terms of talking about capitalism in relationship to art, it had to be Warhol. Yes he does refer to historical subjects, but it’s more about appropriation and repetition, reflecting on the influx of images, repetition and surface.

NA: You could say that Warhol is on the one hand the embodiment of capitalist culture and ideology, but on the other hand, through mass appropriation and the endless turning out of images, he has an ambiguous relationship to his subjects…

NH: I think he is actually quite ambiguous when it comes capitalism. His studio was literally called The Factory. He was really about working with that system, exploiting that system. But I think he had a criticality towards the system at the same time.

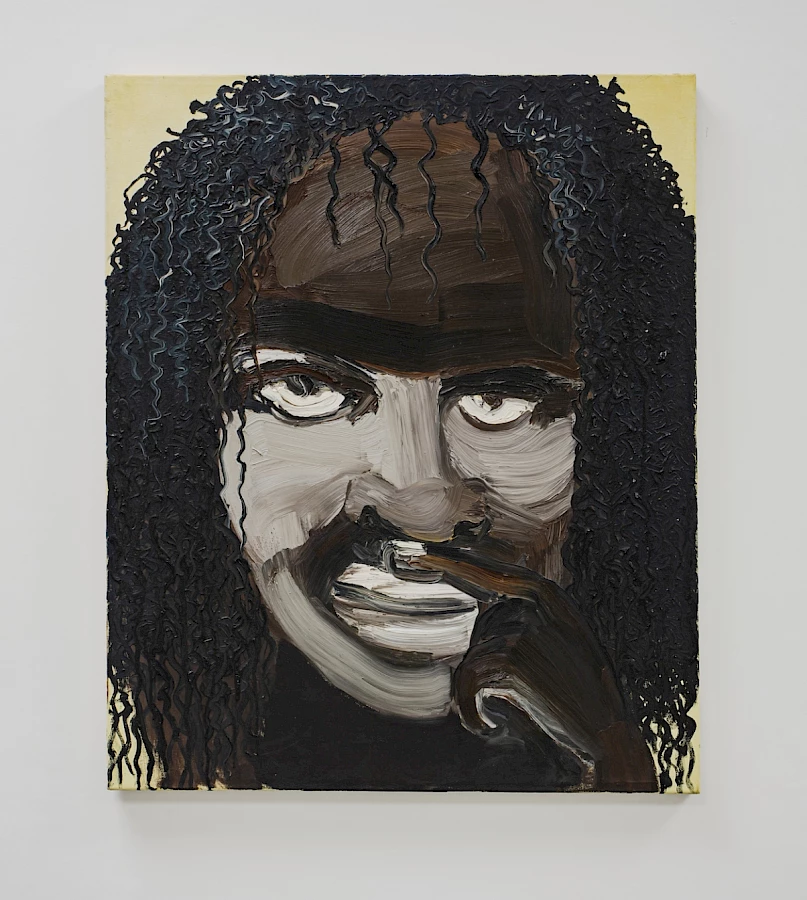

NA: Now we are in what I loosely call the ‘identity politics’ section, typified by the catalogue of the 1993 Whitney Biennial, next to which two of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s portraits are hung. How are we to read this? As an accompaniment or foil to the question of identity politics?

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Nourish the Talented, 2003. Photo: M HKA.

NH: I think there is a constructive discussion to be had about the Americanisation of identity discourse, and whether this paradoxically generates another sort of monoculture. Many years ago, I visited Lynette Yiadom-Boakye in her studio, and through her eyes, her work is not really about ‘black representation’. It is more about invention, the tradition of portraiture, being able to create characters as an artist. People apply the lens of blackness to her work in a way that, I think, creates a dilemma for her. It is different from the Kerry James Marshall that hangs opposite – his work is really about blackness, and what he calls ‘rhetorical blackness’. Yiadom-Boakye is often put in the same category, and that’s not always insightful.

NA: Then the Philip Guston painting, Law (1969) – I guess his inclusion came well before the debate around the postponement of his planned retrospective by three US museums and Tate Modern, London…

NH: There was never any question of not exhibiting the Guston painting. I’m interested in how he was originally an abstract expressionist painter, and then at a certain point he made a decision to do something entirely different, which he became famous for – the sort of cartoonish, almost absurd painting style. In a way, this work is to do with his family history and biography. For ‘Monoculture’, it was a way to talk further about the American context, and the fact that the US had their own equivalent of white supremacism in his lifetime, which sheds light on the contemporary. This is why I placed it in relation to artefacts from the American eugenics movement and racist literature.

Foreground: Jimmie Durham, Tlunh Datsi, 1984. Background: Andy Warhol, The American Indian (Russell Means), 1976. Photo: Evenbeeld.

Jimmie Durham, Tlunh Datsi, 1984. Photo: M HKA, Wim Van Eesbeek.

NA: The display sets up a complicated quandary for a visitor – to look at these publications and then to look at Yiadom-Boake’s work, to read these images in relation to these histories of violent ideas. You make challenging demands on the viewer, to figure out their relationship to what they are looking at.

Before we stop I want to move into this room, where we have orientalism, via Edward Said, writer John Berger, and art historian and broadcaster Kenneth Clark. There are three corresponding television programmes, so there is a reference to the mediation and popularisation of certain ideas through television.

NH: This room tries to deconstruct the hegemonic gaze, and then to open up to new perspectives, which is one of the basic principles of postmodern relativism. So this zone is more in the mode of questioning modernity and the dominant Western worldview.

NA: In relation to these three positions Haseeb Ahmed’s vast installation, Ummah HQ (2020) and Rasheed Araeen’s Nine (1968). It is one of the moments in the exhibition where the artworks and ideas (as presented through artefacts) coalesce. Araeen’s work speaks to the original notion you discussed for the exhibition – equality. He talks about the relationship between symmetry and equality, of one side equalling the other.

NH: Ahmed’s installation refers to the mutually supporting architectural form of the Muqarna in Islamic architecture as a metaphor for the construct of the ummah [the community]. This seemed relevant in relation to [Belgian architect] Luc Deleu’s work Global Center for Interracial Communication (1980), which tries to imagine architecture as a way to solve conflict and racial intolerance. He’s a utopian architect rather like Yona Friedman. These sit in contrast to material related to experiments with architecture in regions like North Africa and India by European modernist architects, where architecture was a colonial export.

Araaen came from a training in engineering to become a pioneer of minimalist sculpture, but as someone coming from outside Europe, he was rejected for it. I was interested in this story in relation to claims of modernist universality, as well as in comparison to [German minimalist] Charlotte Posenenske’s work, which also utilises industrial techniques. Araeen has said that Western modernity was an expression of European identity. However, over time, other places have gone through periods of modernisation, in ways distinct from Western modernity. Using the word ‘modern’ to describe this process might not even be correct, but we are stuck with the vocabulary that we have inherited.

Haseeb Ahmed, Ummah HQ, 2020. Photo: Evenbeeld.

I’m interested, philosophically speaking, in [Israeli sociologist] Shmuel Eisenstadt’s proposition of multiple modernities, which has been adopted in political philosophy as a way to talk about the new global reality: the fact that the Sinosphere, for example, is constructing its own modernity, so that we end up in a situation not of universal experience, but rather of competing modernities. This idea will be at the core of our Eurasia project later in 2021.

NA: To close let’s bring the ‘Monoculture’ project back to the context of L'Internationale. L'Internationale clearly aligns itself with the history of the socialist project. The title comes from the nineteenth-century workers’ anthem and the history of Marxism, which in your exhibition appears through an early edition of Das Kapital. The confederation stands behind pluralism and openness, while at the same time aligning itself with this particular historical trajectory and ideology. In this way, its politics appear unambiguous! Following the argumentation of your exhibition – and to make a provocation – do you see the alignment with the socialist trajectory, or some of the other positions the confederation takes up, in relation to the decolonial, for example, as a certain form of monoculture?

NH: As you say, rhetorically speaking L'Internationale talks about strength in difference and plurality, but I do think there have been some assumptions that we are all somehow the same, that we have the same approach to institutions and practices, and that this can result in a kind of groupthink. I’m not sure that is the reality actually. For example, I think it’s quite clear that some of the institutions are invested in what you refer to as decoloniality, and some aren’t, yet there has been an assumption that all of us are. I don’t think that M HKA really is – it perhaps addresses the same concerns through a different approach – and I wouldn’t say SALT is either. We all work with a sense of critical engagement, and have some shared goals of practicing equality, wanting to create open-minded and reflective institutions, and of course to present great art. But maybe we do this in contrasting ways.

NA: Do you think there is more work to be done in practicing openness and plurality across the museums in the confederation?

NH: I think it’s important that we are not a monoculture. That’s essential for the health of the confederation. The reality is that there are differences here already, but perhaps we need to work better to understand them.

Exhibition view, Monoculture – A Recent History, M HKA. Photo: Evenbeeld.

The views and opinions published here mirror the principles of academic freedom and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of the L'Internationale confederation and its members.

Related activities

Related contributions

A conversation about the project 'A Temporary Futures Institute'

Art Museums and Democracy

Hauntological Relations of Monocultures

A walk-through the exhibition ‘MONOCULTURE – A Recent History’ at M HKA (Antwerp), with Nick Aikens and Nav Haq in conversation

Decolonial Suites

Offsetting Sameness: Notes Towards Artistic and Institutional Polysemy and Practices of/on Monocultures and Multicultures

Panel Discussion with Luísa Santos, Ana Fabíola Maurício and Olivier Marboeuf, moderated by Nav Haq

Constituting the Ummah – أم