Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

In this dispatch from Istanbul, artist İrem Günaydın ruminates on artistic labour, rejection, censorship and institutional positioning in times of genocide.

The title borrows the phrase ‘the blurst of times’ from The Simpsons (S04E17), where a monkey, hired by Mr. Burns to write the greatest novel ever, mistakenly types, It was the best of times, it was the blurst of times. The line humorously misfires while attempting to recreate the famous first sentence, ‘best of times, worst of times’, from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. It’s a joke, but one laced with accidental resonance. Referencing the Infinite Monkey Theorem – the idea that a monkey hitting keys at random for an infinite amount of time will eventually reproduce any given text – the scene absurdly collapses infinite possibility into a single moment of near-success, foiled by one misplaced letter. That tension between genius and gibberish, effort and error, is not unfamiliar to artists. Contemporary artistic labour often feels like typing into a void: endlessly producing under pressure, often misread, often rejected. Like the monkey’s almost-profound failure, the artist’s work exists in a system that demands legibility and punishes deviation. This essay takes that slippage seriously. ‘The blurst of times’ signals a fractured present – one that feels absurd, tragic, and numbingly familiar to artists navigating today’s institutional landscape.

The inbox fills with rejections, or worse, silence. Application after application disappears into the ether of institutional indifference. Meanwhile, the art world continues to applaud the photogenic, the digestible, the vaguely ‘urgent’ work that somehow avoids naming anything at all.

I’ve begun to think that rejections form a kind of shadow practice. They build up like sediment. They shape the rhythm of our work more than any exhibition deadline. And strangely, they sharpen something too: a clarity, a resistance. To keep applying in the blurst of times, knowing the system prefers the silent, the fashionable, the unlooking, is itself an act of critique. Perhaps to keep making after rejection is not only to persist, but to insist: that the work is not dependent on applause, that the only value is not in being seen, but in continuing to see otherwise.

In a field increasingly driven by visibility metrics, resisting the urge to be legible in the present becomes a form of artistic dissent. It opens up space for work that doesn't yet fit, that lags behind or runs ahead of the institutional clock. In these blurst of times, to be an artist is to practice refusal, not only of what to depict, but of what to become.

Today, institutions champion works that perform urgency without holding any real stakes. The fashionable thrives precisely because it is non-threatening; it circulates easily, decorates, and affirms the institution’s self-image as progressive, without asking it to take risks. This dangerous mediocrity is not accidental. It’s selected. Curated. Funded.

We live in the blurst of times – where major cultural institutions choose to ignore the genocide in Gaza, remain silent on censorship (if not enforce it), and turn away from state violence. That logic trickles down: when an institution refuses to speak, it rewards work that doesn’t speak either. It prefers art that looks away. Even institutions beyond the so-called ‘centre’, those calling themselves ‘critical’, often adopt the same posture. Many strategically perform a reverse Orientalist aesthetic: narrating the ‘East’ as bruised, lyrical, and manageable enough to fit, never enough to disrupt.

Their fluency in institutional language allows them to frame work within familiar, grant-friendly tropes, trauma, identity, ecology, colonialism, solidarity, and displacement, but only in exhibition-ready formats. These themes don’t circulate for what they provoke, but for how easily they can be contained. Compressed into wall texts. Filtered into press releases. Art that fits the expected image of the Global South: poetic in its suffering, polished in its despair, composed to remain recognizable. These institutions mirror the logic of Western validation. They maintain their place by appearing to look. But they are not looking. Not at Gaza. Not at censorship. Not at what hurts.

There is always a fashion in art. It changes its clothes every few seasons: the anthropocene, the archive, the glitch, the healing ritual, the wound. But like any fashion industry, it demands surface. It wants just enough content to be legible, just enough pain to be moving, just enough political suggestion to be admired, but never too much. Never enough to rupture comfort or implicate the institution itself. Trauma, but poetic. Identity, but beautifully staged. Displacement, but with high-resolution images. 8k, preferably. The institution doesn’t want the mess, the complexity, the politics; it wants the performance of relevance. This is how critique is neutralized: through framing. This is how art is disarmed. The institution absorbs. It flattens. It selects the version of a theme that is most palatable, feasible, visually appealing, and exportable. And in doing so, it determines who gets visibility, not based on depth or resistance, but on how well an artist’s work can be framed within its own spectacle of relevance.

What happens when you do not comply with these frames? When your work cannot be reduced to a fashionable caption? When your voice does not echo what the institution wants to hear? What happens when you name the unnameable and stand with the silenced?

You face censorship, indifference, or rejection.

This is where rejection becomes more than a personal defeat. It becomes structural. Ideological. The artist who does not flatten becomes a threat, not because of radicalism, but because they insist on another kind of seeing.

The inbox is still mostly quiet. But maybe it’s not silence, it’s sediment. The layered remains of refusals that signal the work has not folded itself to fit. Each unanswered proposal, each curt rejection is not a void; together, they are a counter-archive. They mark the refusal to be compliant, the refusal to become fluent in the expected dialect.

And in this quiet, counter-archive, something holds. Not hope, necessarily. But continuity. A slow, stubborn insistence that there is still value in making the work, even when no one is looking, especially when no one is looking.

Below are photographs from İrem Günaydın's ongoing series – unsanctioned, site-specific inscriptions written in lipstick on museum restroom mirrors, each beginning with 'The museum is…' to reflect, distort, and confront the institution’s presence, politics, and self-image as an artist. All images courtesy the artist.

The museum is a bank — SALT Beyoğlu, İstanbul, 2025

The museum is gentrification — Arter, İstanbul, 2025

The museum is not İstanbul—İstanbul Modern, 2025

The museum is orientalism — Pera Museum, Istanbul, 2025

The museum is a brand — Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Istanbul, 2025

The museum is the nation — İstanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture

The museum is a battleship — İstanbul Naval Museum, Istanbul

Related activities

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

HDK-Valand

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

Moderna galerija

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

WIELS

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

WIELS

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels. Rana Issa and Shayma Nader

Join us at WIELS for an evening of fiction and poetry as part of L'Internationale Online's 'Collective Study in Times of Emergency' publishing series and public programmes. The series was launched in November 2023 in the wake of the onset of the genocide in Palestine and as a means to process its implications for the cultural sphere beyond the singular statement or utterance.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

–

International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People: Activities

To mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People and in conjunction with our collective text, we, the cultural workers of L'Internationale have compiled a list of programmes, actions and marches taking place accross Europe. Below you will find programmes organized by partner institutions as well as activities initaited by unions and grass roots organisations which we will be joining.

This is a live document and will be updated regularly.

-

–SALT

Screening: A Bunch of Questions with No Answers

This screening is part of a series of programs and actions taking place across L’Internationale partners to mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People.

A Bunch of Questions with No Answers (2025)

Alex Reynolds, Robert Ochshorn

23 hours 10 minutes

English; Turkish subtitles

Related contributions and publications

-

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Rewinding Internationalism

InternationalismsVan Abbemuseum -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

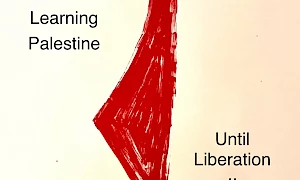

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale ConfederationEN caInternationalismsStatements and editorials -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay PrashadInternationalismsSonic and Cinema Commons -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

S come Silenzio

Maddalena FragnitoEN itInternationalismsSituated Organizations -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

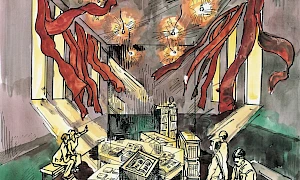

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cinq pierres. Une suite de contes

Shayma NaderEN nl frInternationalisms -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Alissar SeylaInternationalisms -

Today, again, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalisms -

Isabella Hammad’ın icatları

Hazal ÖzvarışEN trInternationalisms -

To imagine a century on from the Nakba

Behçet ÇelikEN trInternationalisms -

Internationalisms: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardInternationalisms -

Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

İrem GünaydınInternationalisms -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials -

Poetry Against Language Dioxide

Rana IssaInternationalisms -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations